I first discovered East Fork Pottery when it was featured in the agency’s internally curated holiday gift guide last year. I was drawn to the character, color and cohesiveness of the line. Being a very tactile person, I ordered some bowls for myself (in Eggshell). I opted to buy from “seconds” (pieces that don’t meet the stringent requirements of East Fork) because it was structured in a very unique way. I could only get access to shop after I donated to a charity in their community. It was only after I later researched the company that I learned that Alex was the great-grandson of Henri Matisse.

East Fork Pottery has been experiencing such an aggressive growth streak. When you and your wife Connie started the company, what were you hoping East Fork would become?

The only thing that I knew I wanted to do was make some mark on the world, as a lot of people do. I went to college, was miserable, got into a pottery class, and a year and a half later dropped out to do an apprenticeship. Pottery was the one medium I really always loved. After three years of apprenticeship I founded the company. I quickly got folded into the scene of potters in North Carolina, South Carolina and the Southeast. There’s a long history of pottery where we are located in North Carolina. It continued through the Industrial Revolution and then it shifted and changed to this art pottery movement. When we started the company I was making pots and selling them to collectors in the southeast and doing small gallery shows.

Then our friend, John, joined as kind of our third co-founder and business partner. He had finished his apprenticeship in pottery. It was a very unusual format — normally it’s one person making and selling their work. And then Connie started following us around with an iPhone, and the three of us started to hatch this plan to take the thing that we love, that we had dedicated our life to, and try to kind of grow that, to speak to a wider audience.

Around that time, ceramics was having another moment in the sun. Ceramics is one of these enduring practices that people love. It has these moments of cultural relevance. We saw people in Brooklyn and LA, young potters who had taken a few community classes, and were getting noticed for their work with big Instagram followings. We felt like we had something to add to that conversation. So we put together a little money, bought a gas kiln, and just kind of flipped the switch immediately from what we were doing and that first kiln opening.

When we debuted the new line, what you see as East Fork today, nobody showed up. It was just crickets. And we just sort of sat there, like what did we do? But eventually it started to gather momentum and we couldn’t keep up.

Now we operate a factory that’s very industrial, but back then it was a potter’s wheel with a kiln that was about 30 feet long. We fired it a few times a year, a very labor-intensive process. We made pots in a kind of vernacular that spoke to my training, and these histories of potters that came before me.

You learned pottery on the wood-fired kiln which has a lot of character with its hand made approach. Has it been challenging for preserve that character with your new gas-kiln manufacturing method?

What we wanted to retain in the pieces was the formal quality. There is some material quality that we have kept. Like we use a clay that is an iron bearing clay. We fire it in an atmosphere of reduction, which brings out the iron spots, so those iron spots are not faked. There’s a lot of pottery out there where they’ll sprinkle some oxide on it to fake that kind of craft look.

The bowls are bowls that we used to make by hand, but now the interior surface quality is smooth. You don’t see throwing lines, ’cause we didn’t want to fake it. We don’t want to say this looks like it’s a handmade piece, but it was made on a machine. We’re not interested in pulling that over on someone.

Your mug has a pretty big cult following. How did you find that silhouette? What was behind the decision to do an exposed rim?

That mug was maybe one of our largest departures, because we used to make mugs that were curvy and round. We were really trying to pare something down to its most simple essence. We wanted the shape to be flat, like the mugs you see when you go to diners across the US. The part of the mug that I think is the most unique is the handle, which was designed off of a pulled handle. If you’re a potter, one of the ways you make a handle is you take a little sausage of clay, and you smush into the top of the mud and then you wet it and then you gradually pull the shape of that handle. The handles that we made had a really wonderful feeling in the hand, and we wanted to preserve that. So we kept a very straight silhouette and we added this beautiful handle, which we worked on and worked on and worked on.

And then we have an exposed rim on all of our pieces. The reason for that is because the first glazes that we used weren’t incredibly stable and they shivered, which means they cracked when they went rounded over that surface. And so we thought, well, we’ll just wipe that off. And it stayed with it.

You have a very interesting business model where you’re creating a revival of artisanal manufacturing as well as servicing the community by making the people around you whole.

The first part around the manufacturing is simply that it’s a wildly exciting thing to learn about an industry that is almost completely gone in the US. Essentially all of the big ceramic manufacturers have closed. I love the challenge, and our whole team loves the challenge, of walking into something with a beginner’s mind.

Offering a good manufacturing job is also really important to us. We came to this as artists and writers, not businesspeople. So there has to be more to it than just the bottom line. We are motivated to make the work better and to keep offering better pay and better benefits as we grow. We look at how we can make what is typically a blue collar job not feel so blue collar all the time?We have a chef that cooks staff meals for everybody in the company twice a week. We’ll do it every day when we can. We want to offer childcare as soon as we can.

We’re just at the cusp of growing. This past year was actually the first year we’ve posted a profit since we’ve started this growth. It wasn’t much of a profit, but next year it’ll be much better. And as we find our footing and become more financially stable, we can start rolling out more of these things that really excite us.

A percentage of your sales goes towards non-profits in your community in North Carolina, right?

We do a few different things. We have a values team who focuses on who we’re supporting and why we’re supporting them. We like to work with smaller grassroots organizations where the smaller dollars that we’re able to raise go further. We’re not giving away millions of dollars. We’re giving away $25 or $50,000, but that can be a game changer for a small nonprofit doing really important, big work in their community. It’s part of our DNA at this point.

Your direct-to-consumer model is kind of infused with this purpose-based branding, which is really exciting. How did the Pinto line you just launched with Samin Nosrat, who wrote Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat come about?

We have started to think about how we can collaborate with more people larger than us. We love Samin. Our kids love her show. We’ve watched it multiple times. We got an introduction to Samin through a mutual friend, then over six months, we nurtured the relationship. It was really Connie doing that work. And Samin said, “Here’s some colors that I like.” There was this dahlia from her garden, and then this kind of antique brass, and we went back and forth with glazes and then eventually settled on Pinto.

The colors you choose for your collections are so beautiful. Even the names, like “Night Swim.” It’s such a great name. What role does color play in the creative process?

When we made the switch from firing and the wood kiln, suddenly the world of color opened up in a way that we hadn’t explored it before. Connie is the one who really is spearheads all of that work. She gets out ahead of the trends, because our development cycle can take six months to a year.

There’s an organic process to it, because the way that those colors are formulated, we’re mixing different oxides together. We come up with a range of colors. From there, Connie picks and chooses. And then our glaze chemists will start mixing up the sample, and sometimes new things emerge from it that you weren’t expecting. But for the most part, they get really close to what we’re looking for. It’s amazing to see over the last three or four years how many colors now exist, how people put them together in all of these beautiful unexpected combinations. We look back on some colors and we’re like, “Whoa, that color. It really wasn’t a very good color, but it’s part of the story.”

Do you have a favorite?

I do like Night Swim. I liked a color called In the Pines, which was another green that we did a long time ago. We also did a color called Harvest Moon, which this kind of rich umber yellow. Favorites are hard for me. I was a big fan of Soapstone. And if I have my way, it will come back someday.

Food seems to be an integral part of your story. What roles did it play in the formation and development of the brand?

Food is obviously the reason that we make what we make, and it’s always been a part of what we do. And more than just food, hospitality. When it was just a few of us in Madison County, we would break for lunch every day and we would sit underneath this old apple tree, outside the little farmhouse, and we’d all have lunch and one person would cook every day. So when we moved into the office, the factory where we are now, we built a commercial kitchen. It’s always been in our DNA. Food was incredibly important to Connie and her family growing up. We will open a restaurant someday. That feels like an inevitability.

Now talk about art. I know you come from long artistic roots, but how did that shape your formation?

Yeah, it’s funny. The art is probably less of a direct tie. My relationship with Matisse, who is my great-grandfather, is more complicated. The influence there was really in the intensity of how you approach something. There was this drive in myself, this kind of competitiveness to do something of some scale. What I love now about East Fork is that the people that know East Fork don’t know necessarily that there’s a connection to Matisse. That has faded into the background, which really, for me, feels like a success. When I used to make pots on my own, people would say, “Hey, can you sign the bottom of this?” And now East Fork has blossomed into this thing that’s really its own, and that’s really wonderful.

You come from a long legacy of artists, correct?

Yes. My father and mother are both artists. I grew up surrounded by their art, and by art from Matisse, My grandfather on my father’s side was an art dealer, Pierre Matisse, who had a gallery in New York. I was always surrounded by it. On the other end, my grandparents on my mother’s side were anthropologists. And that kind of connection of art and anthropology created some sort of fertile ground that I think my love for ceramics grew from. The utility, and creativity.

Isn’t pottery one of the oldest art forms?

Yeah. People have always had a need to scoop water out of a creek and hold something.

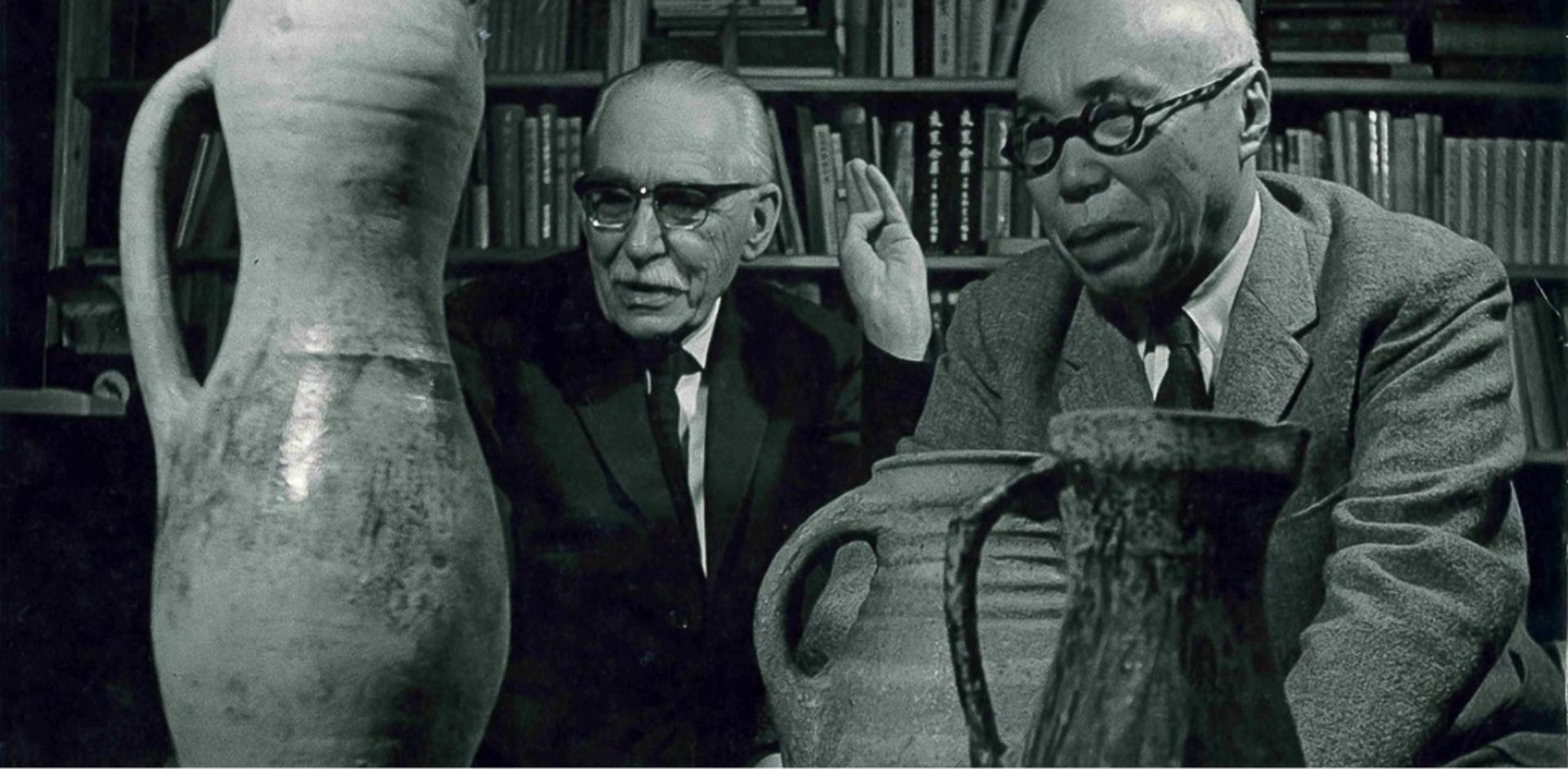

I know you have a connection to the Asian ceramic potter who brought this idea of everyday utility and beauty, back in the 1940s. I’ve always been really interested in the concept of wabi-sabi. It’s just such a beautiful sentiment and that really kind of manifested itself in pottery — showing and celebrating the use.

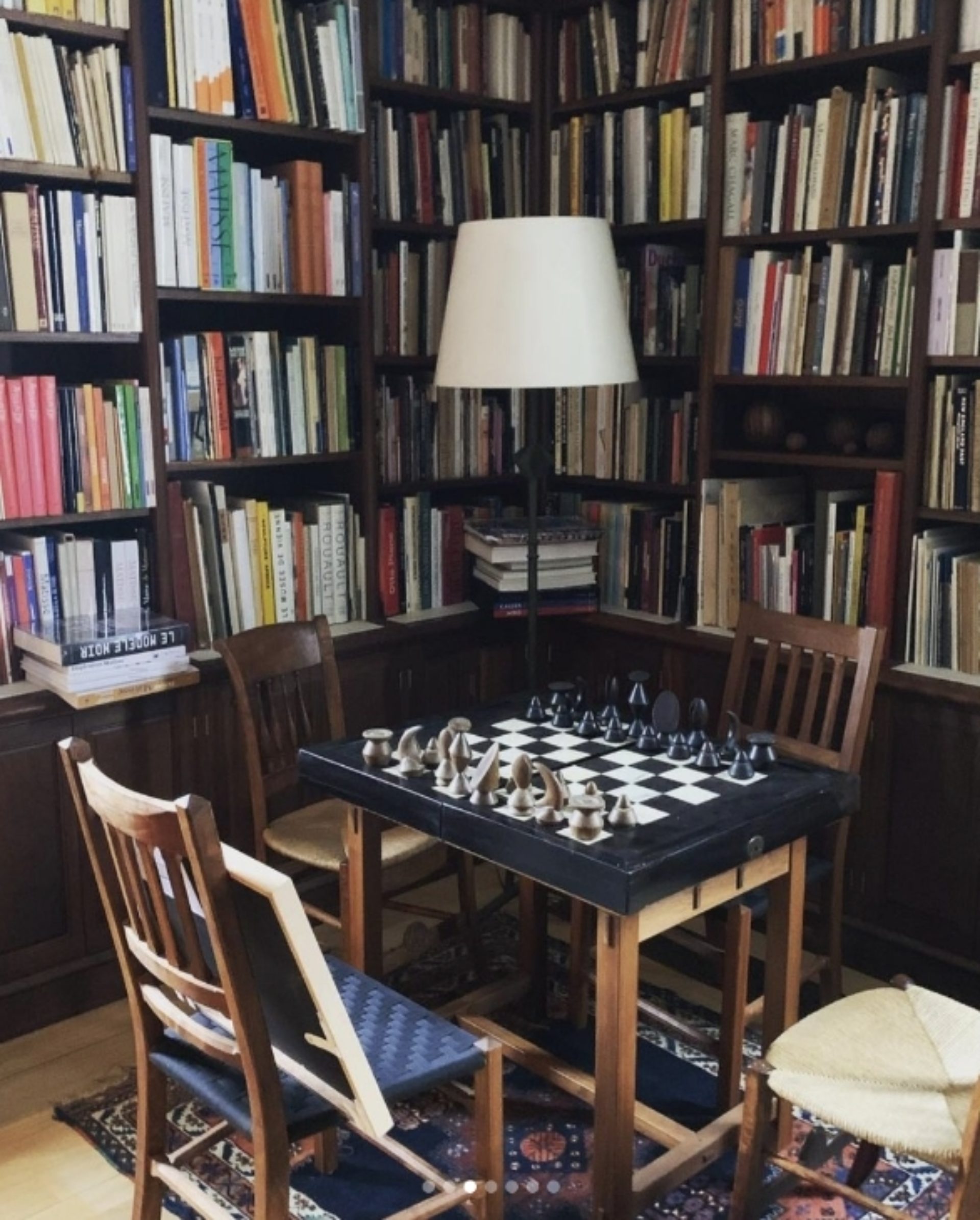

Yeah, we could do a whole interview on that. That came from two potters who had a relationship, Shoji Hamada in Japan and Bernard Leach in England. They’re kind of considered the godfathers of a specific movement. Wabi-sabi is the term a lot of people recognize from Hamada in Japan. A lot of that came from looking at old pots and old tables that were made for utility, but made with so much life and so much movement. They were made so quickly because they were made to use.

Bernard Leach met Hamada and they struck up a friendship where there was a passing of information and ideas back and forth. Leach saw old English slipware pottery, and saw within that a lot of similarities to what was happening in Japan. The potter that I apprenticed with was a sort of a disciple of one of Bernard Leach’s most famous apprentices. All of these apprentices are kind of spread out and they have their own apprentices, so there’s a lineage that’s sort of passed on. When John and I started thinking about this growth, we were really thinking of how we could do something remarkably different from this lineage. How we could break out of that tradition and add our own thing.

You talked about the restaurant. What other some other things are you hoping to accomplish with the brand?

Right now we’re in a small factory, but we want to build a campus that feels like a forever home for East Fork. Over the next few years we’ll be working on that. I look in the future and I look at companies like Patagonia, and that’s the type of organization that we’re building towards. But at the same time we’re also realists, and those organizations aren’t built by setting out to build a billion-dollar company. Who knows what the future holds, but we protect our independence. We want to maintain control. We want to build something of size and scale, but we want to do it while retaining the soul of the thing.

You do seem to stand apart from the direct-to-consumer kind of brand that is just on this accelerated trajectory and is all about growth. It’s interesting to hear about how Patagonia is a lighthouse for you because they have grown intentionally over time.

You brought this up earlier. A lot of companies are sort of starting to take a stand, and when it’s not baked into your DNA, when it’s not your core operating principle, people sniff that out. And Patagonia is an example of a company that just lives and breathes it. One day I’m going to get Yvon (Chouinard, founder of Patagonia) in a room and sit down. Or what I’d really like to do is go fly fishing with him.

Last question, and I ask this to everyone: how would you define beautiful thinking?

People always ask me, “Do you miss your craft? Do you miss the work that you used to do?” And for me that idea of beautiful thinking, the idea of craft, comes down to how much devotion you put into the work that’s your everyday work, that’s right in front of you. And so for me, craft is the same as beautiful thinking, There’s a craft of growing this business. A lot of it comes down to challenging the ways that people have doing things before, being passionate and driven to do something that’s, that’s extraordinary. To me, it’s simply about the the intensity that you bring to even something that is mundane.