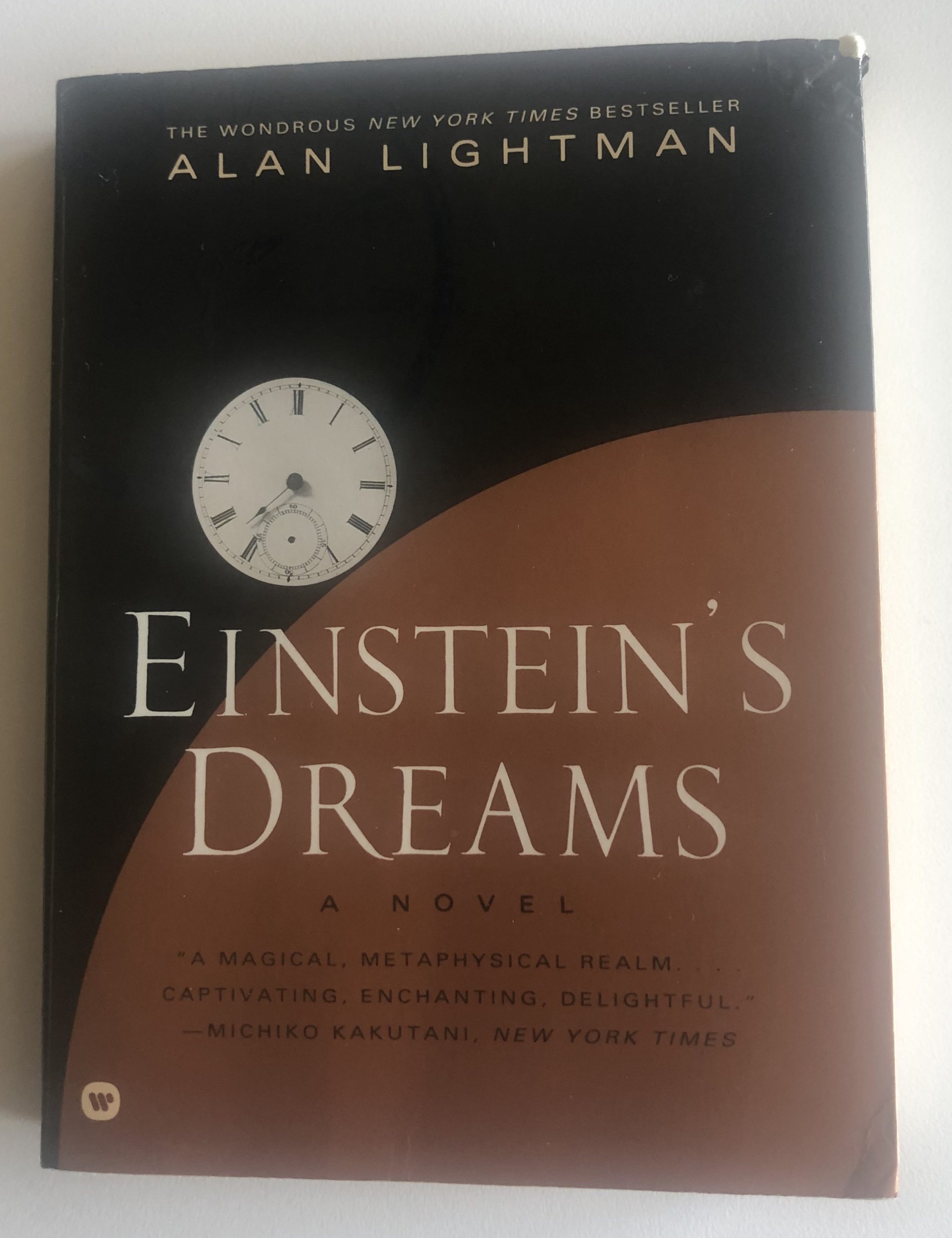

I first discovered Alan Lightman when I was given a copy of his book, Einstein’s Dreams as a Christmas gift nearly 20 years ago from a creative colleague. I read it over break that year and was entranced. It was a creative science book that explored different fictitious theories of relativity as only a physicist could. It has since become my go-to gift for creatives as an exercise of how to view the same topic from multiple angles—a necessary skill for a good creative. When I saw he’d recently written a new book, non-fiction this time, that Oprah interviewed him about, I knew he had to part of this season. He might possibly be the first beautiful thinker I encountered without even knowing it so many years ago.

“One night I was coming back from the mainland and I turned off the boat to lay back and look up at the stars. I had that feeling you have as a child when you look at the stars. I started to feel like I was falling into infinity. I felt like I was part of them, not only part of the stars, but part of nature, part of the cosmos. And I had this very weird sensation of time getting compressed to a dot of the infinite past long before I was born. And the infinite future, long after I will be dead.”

You have a very unique background being raised by a father who owned a movie theater, and a mother who was a dance teacher and a volunteer braille typist. How did growing up with that set of parents inform your passion to become the scientist and author that you are today?

My parents were both very open-minded. And I think that made me feel like I could do anything I wanted. They did not push me into joining the family business, which was movie theaters. Neither one of my parents was a scientist, so my interest in science came from my own DNA. Well, of course my DNA is their DNA, but it began with me. They encouraged me to do what I wanted to do, and I developed an interest in both the sciences and the arts from an early age.

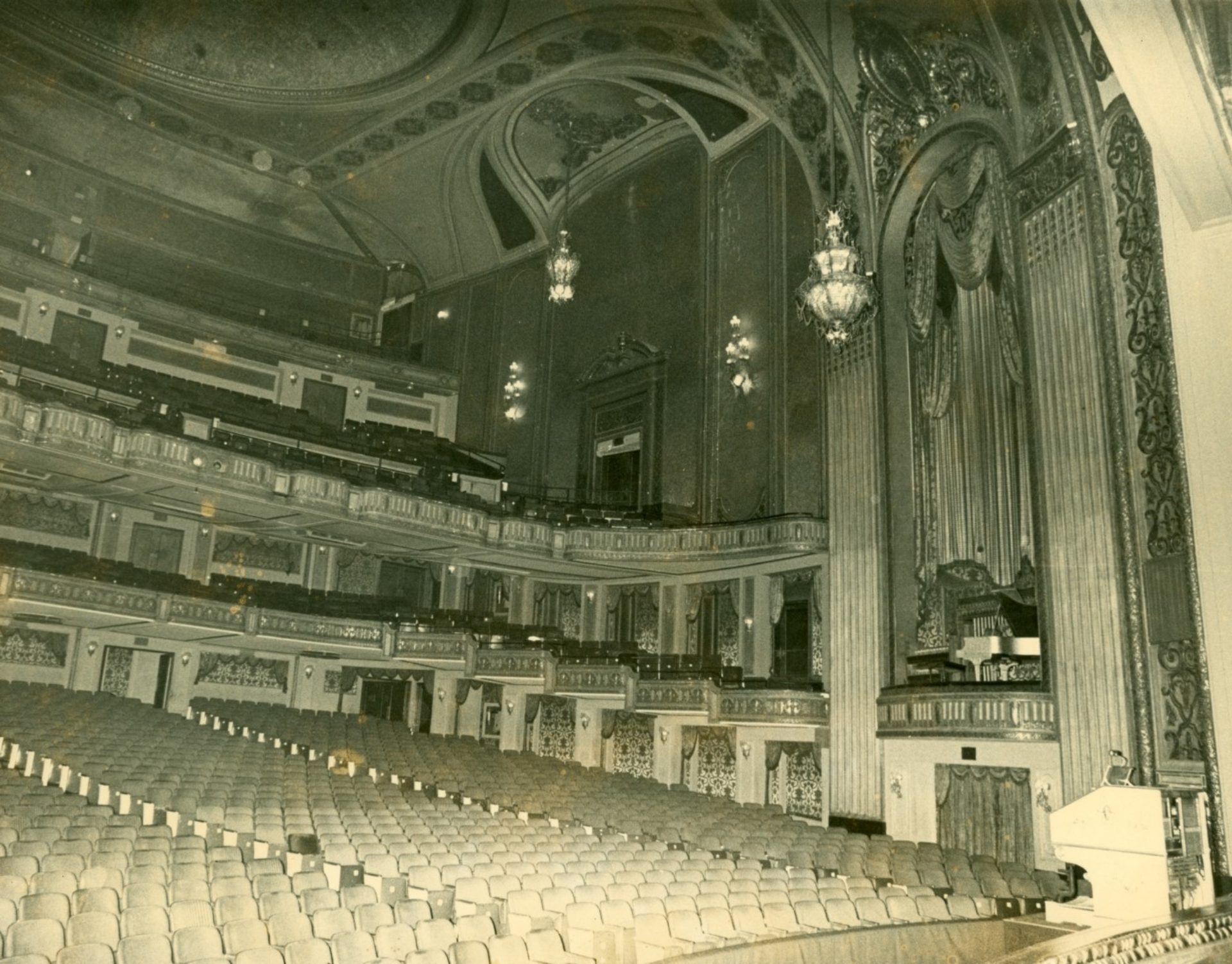

Movie theater that Alan’s father owned. “In 1940, Malco Theatres purchased the Orpheum Theatre, a former vaudevillian theatre in downtown Memphis, and renamed it The Malco. This opulent movie palace at 89 Beale Street also became the base of operations for Malco Theatres until 1976.”

Did you ever feel pressure to choose between science and art? Those two disciplines often are opposed.

I can’t explain why exactly, but my teachers and my friends pushed me to go in one direction or the other, to either be a scientific type or be an artist type. I had some friends who got excited about doing their math homework every night and other friends who wrote poetry. I seemed to move back and forth between the two groups of friends without any trouble. It was later on in college when I realized that that most people either were the deliberate, rational scientist types, or they were more intuitive, spontaneous artist types.

Did you ever feel like you were taken less seriously in one world or the other?

A lot of young people who have an interest in both the sciences and the arts come to me for advice on this. I tell them I believe it’s very important to be well-grounded in at least one discipline. At some point you may become interdisciplinary and start mixing poetry with engineering or whatever. But to be taken seriously and really to be good at what you do, you need to go deeply into at least one field.

Even though as a youngster I recognized that I had interests in both science and the arts, I did know that when I got to graduate school, I needed to really deepen myself in the sciences. And so that’s what I did. And that worked out very well for me because I was always taken seriously as a scientist. But of course, to be an artist, you don’t necessarily need formal training in the arts. You just need to do it and to learn from other artists. And so I did that. I had a long period where I was reading lots of other writers and trying to absorb what they were doing and writing stories of my own. I joined a writer’s workshop. So I did sort of pay my dues as a writer later on.

Early rocket built by Alan where he mixed his own rocket fuel when he was 14 years old. (And yes, it worked.)

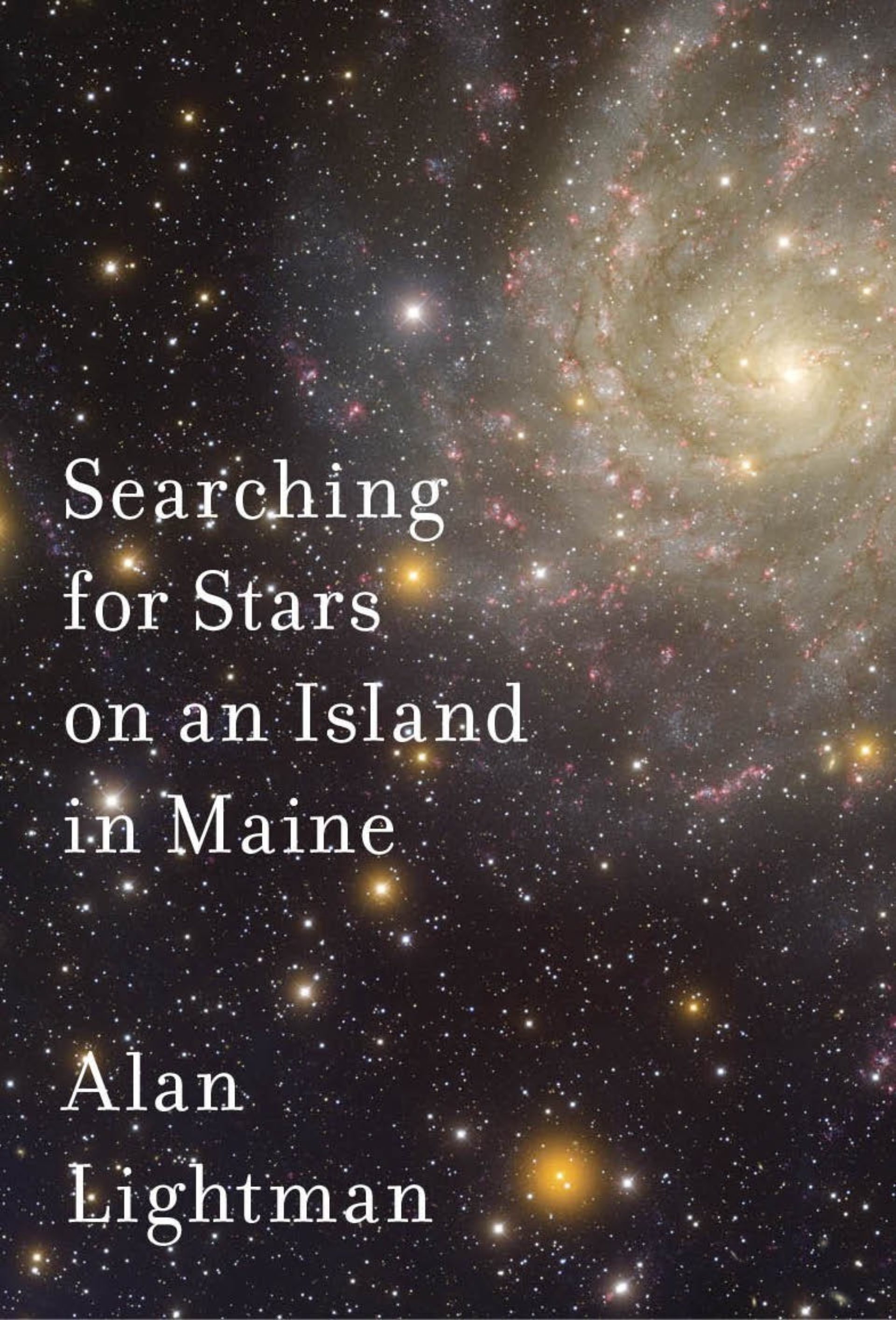

Left: Einstein’s Dreams, published in 1992 was an international bestseller and has since been translated into thirty languages. Right: “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine is an elegant and moving paean to our spiritual quest for meaning in an age of science.” — The New York Times Book Review

You instituted a new communication requirement at MIT, which required all undergraduates to have some equivalent of writing or speaking each of their four years. What led you this thought and what impact has it had on the students

About 20 years ago at MIT, one of the temples of technology, some of us on the faculty began concerned that our students were not writing up to snuff. We actually did a survey of various companies that employed our graduates and ask them what were the skills that they most valued for incoming employees and almost all of them put communication skills at the top of the list, even engineering firms. So that was the leverage that we used to get the entire faculty to agree to this new communication requirement. We could practically translate communication skills to dollars and cents. If you can translate something into money, it boosts your argument.

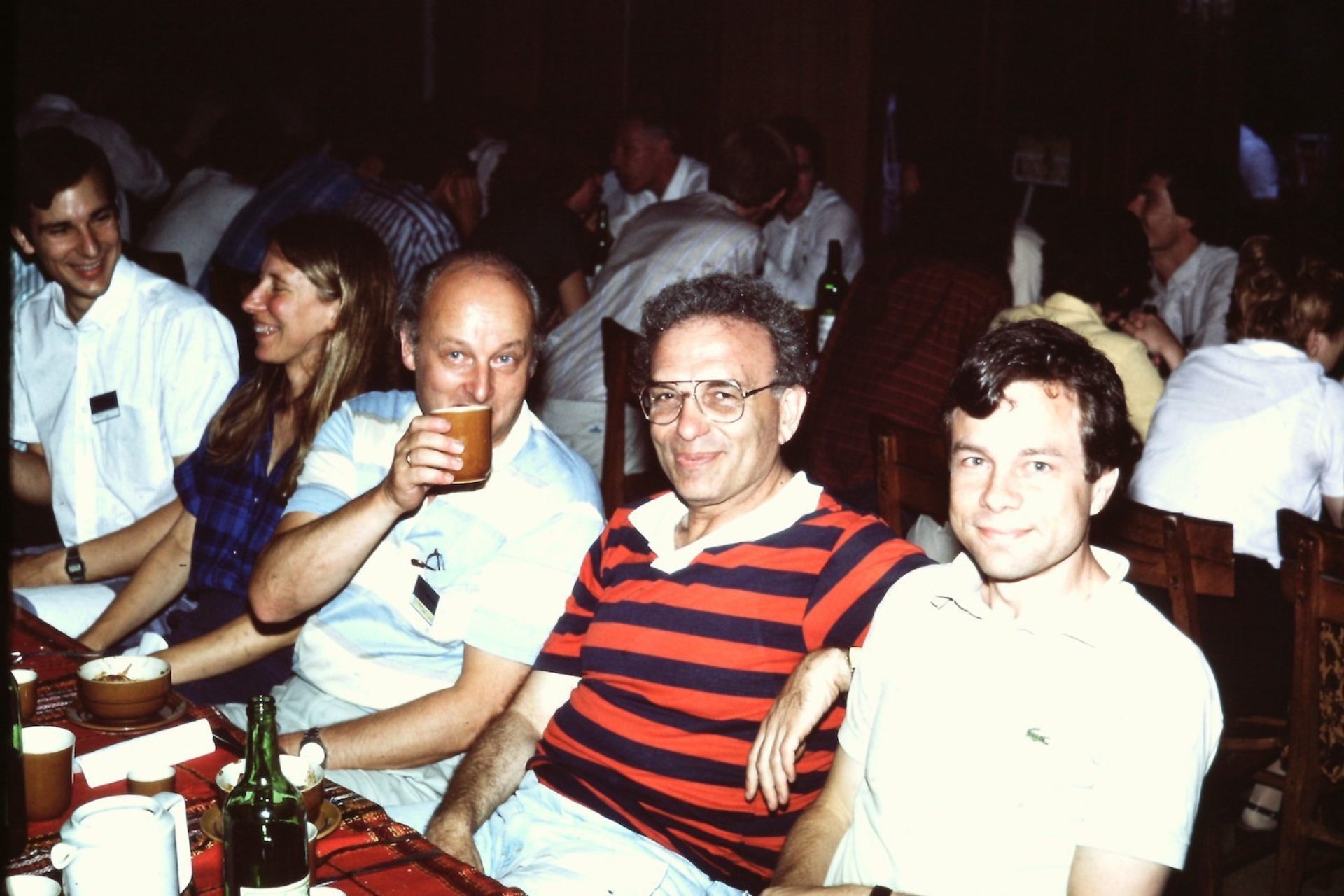

Alan in 1987, (far right) an assistant professor of Astronomy at Harvard at the time, attended an astrophysics conference with his colleagues.

I liked this quote from you, “I love physics, but what was most important to me was living a creative life.” When did you say that, and how did you come to live that philosophy?

I don’t remember when I wrote the quote, but I remember when I had the realization. I was a graduate student in physics in the early to mid-1970s. And when you’re a graduate student in one of the sciences, you have to eat and sleep your scientific research, like 24/7. It’s very intense. And I realized that most of my fellow graduate students were probably going to have careers as professional physicists for the rest of their lives. I realized that I did not have to be a physicist for the rest of my life, but what was enormously important to me was to live a creative life.

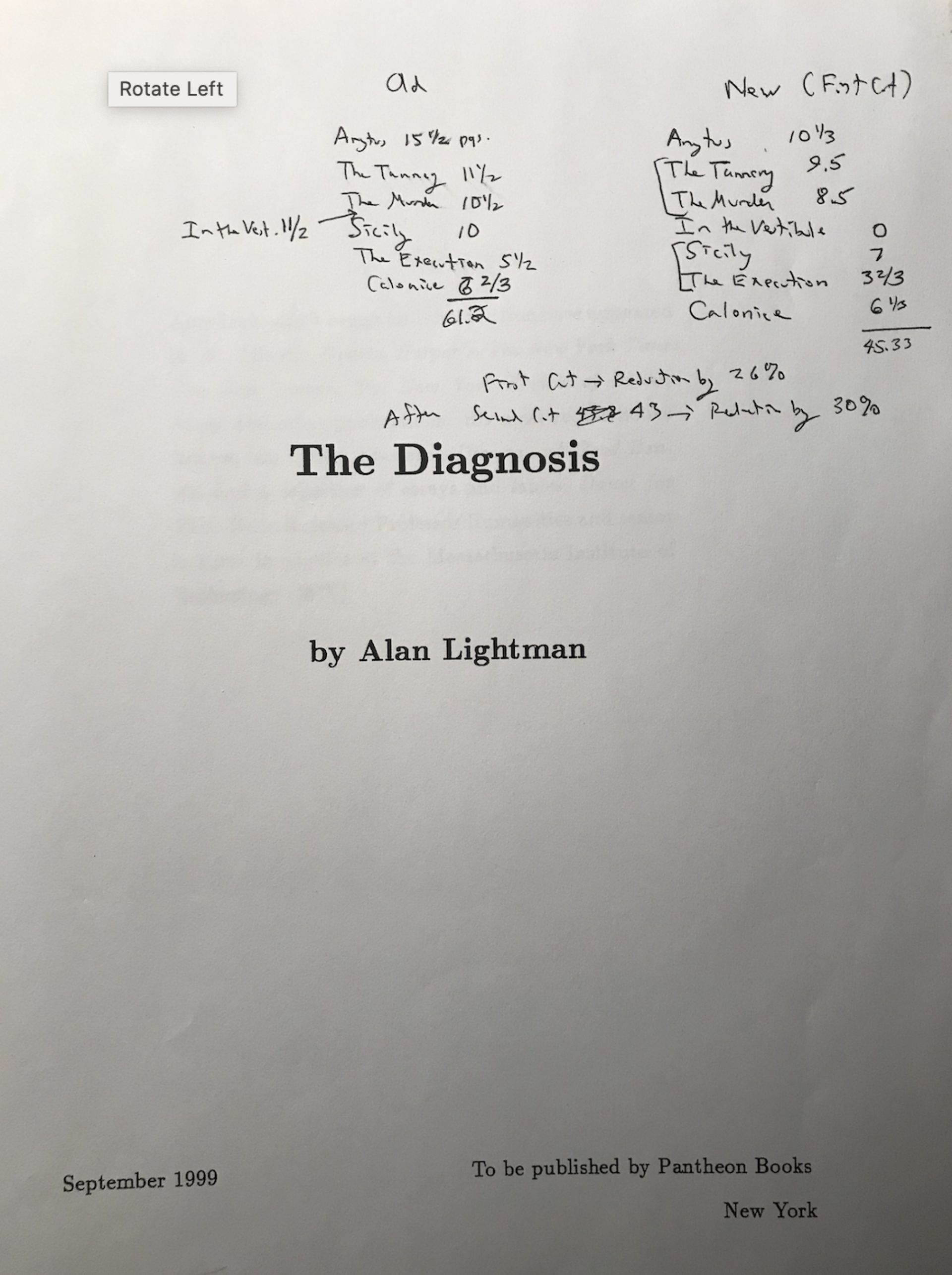

Left: Early science paper published in The Astrophysical Journal by Alan on the instability of black holes Right: Manuscript cover for a fictitious story of one man’s harrowing struggle to cope in a wired world.

And what does living a creative life mean to you?

It’s a combination of going deep into yourself and being open to the world around you, being willing to try to challenge conventions.

Fast forward to 2016 when you wrote, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine. Tell us about the moment on the boat that inspired the book.

My wife and I’ve lived on a small island in Maine for the last 30 years. She’s a painter. And so it’s a perfect site for creative people. The island has only six families on it, and everybody has their own boat. And so one night I was coming back from the mainland to the Island and my boat, and it was very late. I think it might’ve been after midnight. It was a very clear night and the stars were shimmering in the sky. There was nobody else on the water. I could see the Island, but I was not that close to it. And I decided that because it was such a beautiful night. I turned off the engine of the boat. There was no sound, no light from the boat. And I laid down in the boat and just on my back and looked up at the sky.

I had a feeling that I imagine many people have had, if you have a very dark sky and the stars are out. I felt like I was falling into infinity looking at those stars. I felt like I was part of them, not only part of the stars, but part of nature, part of the cosmos. And I had this very weird sensation of time getting compressed to a dot of the infinite past long before I was born. And the infinite future, long after I will be dead, all compressed to a dot.

It was an amazing sensation. And I don’t know how long I lay in the boat like that. My body had dissolved into the sky. And I realized that even though I’m a scientist, that kind of experience cannot be reduced to zeroes and ones, even though I do think that we’re all material. I think that even if you had connected all of my a hundred billion neurons to a giant computer and read out all of the electrical impulses at that moment, that it would not have explained the feeling I had of being connected to the cosmos and dissolving into the sky. And so I I’ve thought since then that there are human experiences that we have that are in that cannot be understood very well in terms of material world. So this is sort of another world between materialism and spirituality. I even called myself a spiritual materialist.

Do you think part of when you felt that was because you were floating and just because you didn’t have the forces of gravity?

Well, that’s a good question, but you could be right. I did have the forces of gravity, ’cause I felt the bottom of the boat pushing up on my back. I mean, I wasn’t really floating, but there was nothing from the external world that was infringing on me, that there were no sounds or emotions from the outside world. It was just this vision of the star-spangled sky. And of course, if you’re lying on your back, looking up, it’s like being very close to a movie theater screen, you know. It was my entire visual field.

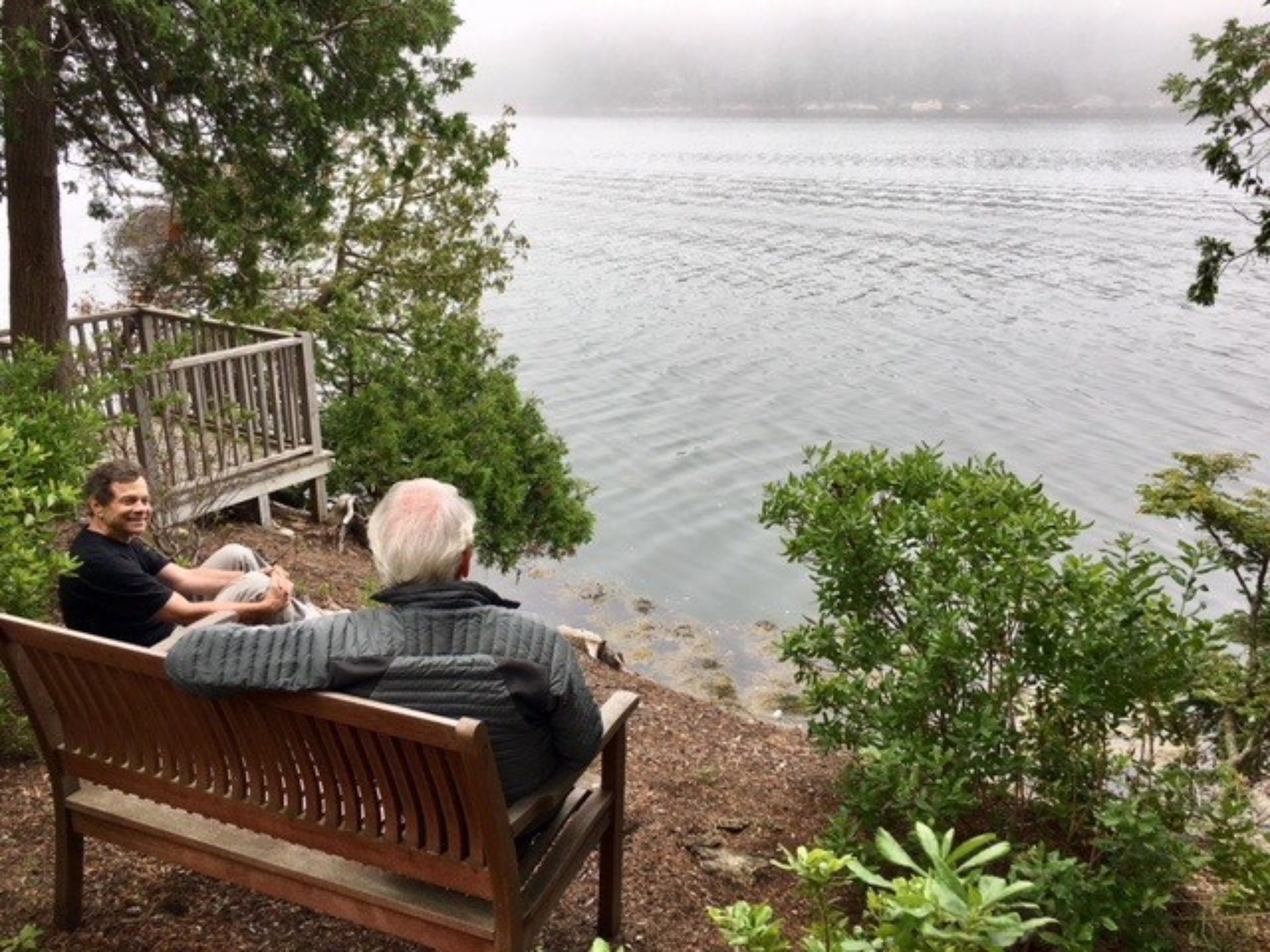

Alan at Casco Bay in Maine where the moment in the boat happened that sparked, “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine”.

What’s been the reaction from the science world to that story? I imagine it challenges a lot of thinking.

Well, if you asked me point blank “do you believe in the supernatural?” which are things that intrinsically cannot be explained by the laws of science, I would say, no, I do not believe in the supernatural. But I do think that the material in our brains is capable of producing extraordinary experiences.

I hope that I don’t turn off your readers here, but there’s something in science and especially in physics called emergent phenomena, and an emergent phenomenon is a phenomenon of a complex system that cannot be understood just by analyzing its individual parts. If you take a bunch of fireflies that suddenly congregate in a field at night, initially, they’re going to flash on and off randomly like Christmas tree lights, not in sync with each other different cycle times and so on. But after about a minute, this amazing phenomenon occurs where they all start flashing in synchrony. So that’s an example of an emergent phenomenon where even if we studied a single firefly exhaustively and knew all the anatomy and all of its biochemistry, that still would not explain how it is that a group of fireflies all come into synchrony when they’re flashing. And I think that our brain is like a hundred billion fireflies. There are qualitative sensations from that a hundred billion neurons that emerge from the complexity of the system and cannot be understood by understanding just a single neuron. So that’s sort of what I mean when I say I’m a spiritual materialist.

You said that it really wasn’t external stimulus that night that created your experience. It sounds like it was more internal, maybe it happened because all of your neurons were firing and your brain synchronized them, like your firefly example.

Yes. Very possibly.

You wrote an article in the Atlantic where you said the virus is a reminder of something we lost long ago. Talk about how our interior life has changed.

Since the Industrial Revolution, and possibly before that, the pace of life has been speeding up and getting faster and faster, especially in the last 30 years or so with high-speed communication devices. That has left much less time for quiet reflection and the examination of our inner life. And I think we really need that quiet time to think about who we are and what our values are and where we’re going. But many of us are just running around so fast checking off to-do lists, checking our iPhones every five minutes, that we don’t take the time to think about what we’re really doing. We need quiet, reflective time to ponder these things. The frantic pace of modern life has really damaged that needed ability, that needed quiet time.

A secret analysis of pedestrians in more than 30 cities around the world revealed that the average pedestrian now speeds along at almost 3.5mph. Photo by Timon Studler on Unsplash

A literal documentation of how much modern life is sped up is this study done by the British Council. It shows that in recent years, the speed of walking has increased by 10%. I mean, there’s no doubt that we’re moving faster than we did 50 years ago. And 50 years ago, we were moving faster than we did a hundred years ago. The speed of life has always been regulated by the speed of business, which has been regulated by the speed of communication. In the 19th century, the high-speed communication device was the telegraph, which could transmit about three bits per second. In 1985, when the internet first appeared, the speed of communication was about a thousand bits per second. And today it’s a billion bits per second. That conveys it right there.

A lot of my readers might be in that same space, wanting to be intentional about a slower pace. What advice do you give to them to foster that behavior?

You can begin by taking 30 minutes a day with no goals. Leave your to-do list aside, leave your phone somewhere, turn it off, put it in a drawer and just take 30 minutes with no particular destination and see how that feels.

Do you think that having the writing side and the humanity side has made you a more imaginative scientist?

I don’t know. It’s the chicken and egg problem. It may be that I always had this imaginative side of me along with the scientific side. They were both part of me from the beginning. I certainly would never present myself as a great scientist. I think that I have been a good scientist, but not a great scientist. But in my scientific work, I do think that I have done things that I considered to be on the imaginative side. And I think that that many good scientists do imaginative things. I believe that good science is a creative activity, and it’s not just following a rote textbook, but it’s actually visualizing physical phenomena and thinking about how things might work and then quantifying that.

Is that part of what inspired you to write your book Einstein’s Dreams?The title of that book came to me first. Those two words juxtaposed together seemed to me to represent the artistic intuitive side of me and the scientific rational side of me that I’ve had since I was a child. Einstein, of course, is the greatest icon of our rational side, and dreams represent our intuitive side. And I began thinking, “How can I flesh this out?”

Getting back to what we were talking out about before, the pace of modern life makes it very difficult for quiet reflection. I think that the dream worlds of time — in which time has slowed down and which we live in the moment — mean more to me now, or that concept of time means more to me now. I mean, the book came out 30 years ago, and I’ve had many life experiences since then and have hopefully matured somewhat. And I have become more aware of the damage done by our frantic pace of life. And so looking back at the book now, I think that the chapters that dealt with living in the moment mean more to me now.

Einstein’s Dreams was very metaphorical and symbolic, but it had a certainty to it, do you know what I mean? Whereas Searching for Stars has a lot more questions. I think a lot of us start with all the answers and then we get older and we actually have more questions than answers.

That’s a very astute observation of yours. You know, all of us change throughout our lives. And I think that every 10 years, we’re different people to some extent. Both books have a philosophical underpinning. And even though Einstein’s Dreams is written in this very declarative manner where each statement is stated with certainty, almost like a declaration, there is a philosophical dimension to the book.

Alan shares a meal with with students of the Harpswell Foundation Dormitory and Leadership Center

In 1999 you and your wife started The Harpswell Foundation in Cambodia. What was the genesis of that?

Jeanne and I made a pact to turn our energies toward humanitarian pursuits. My daughter Elyse and I visited Cambodia and began a project in a small village outside of Phnom Penh called Tramung Chrum. During that time, I met a Cambodian lawyer named Veasna Chea, who told me that when she was in university, she and a few other female students lived in the six-foot crawl space between the ground and the bottom of the school building because there was no housing for young women. Male students could live in the Buddhist temples or rent rooms together, but those options were not open to women.

Veasna’s strength and determination inspired me to create the first dormitory for women in Phnom Penh, which was completed in July 2006. The second dormitory, on the opposite side of the city and closer to many universities, was completed in December 2009.

Last question. I ask this to everyone: how would you define beautiful thinking?

Defining it as thinking about something beautiful to me is sort of mundane. I mean, you could define it as thinking about a beautiful person or a beautiful sunset or a beautiful tree, but I would like to think of it in a more interesting way. Beautiful thinking is thinking that takes you to an unfamiliar but pleasant place.