Joshua’s work is beautiful thinking in action. His work and design processes are unlike any other architect I know. Perhaps it’s his training with OMA founder Rem Koolhaas, or maybe it’s his education in philosophy at Yale before earning his Masters of Architecture from Harvard. Whatever the reason, one thing is for sure: he is quietly but boldly changing the face of design and architecture as we know it.

“When we think about sustainability, we think about how we can design future adaptive reuse into our buildings.”

What are the origins of the name REX?

The name is a pun and has other layered meetings. Architecture has a history of architectural practices that have three letter names— SOM, KPF, HOK, and so forth. When contemplating a name, we worked on our identity with a firm called 2x4, with whom we’ve worked on many projects. They had a beautiful position that a name should be like Wonder Bread, and take on whatever meaning you put on it. People can ascribe meaning and it’ll actually become a stronger and stronger name over time. The original route was the reappraisal of architecture, RE-X, like the variable X. So, redo, rethink, reopen, requestion, rechallenge, reconsider. All of these meanings layer on top of each other.

Design rendering for the Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center at the World Trade Center

The Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center will produce and premiere original works of theater, dance, music, film, and opera. Its concept embodies the Center’s aim to defy experiential expectations, provide unparalleled flexibility, foster artistic risk, deliver the most technologically advanced and digitally connected spaces for creative performance, and engage the local community.

What drew me to you, in your projects and some of your talks, was your approach to your practice as a think tank. How do those diverse disciplines work together?

We look for people who can think, argue and articulate their thoughts. There are certain people on the staff who are either more educated or more skilled at making physical things. But that’s just one of the talents that we need. It’s important to understand that my undergraduate degree was in philosophy. I argue all the time. And I believe in argument not in the sense of arguing, but like argument in making a narrative, to debate something, to get to the core of it. I guess fundamentally we believe that if we can’t argue an architectural solution, then it’s not there yet. And so for us creating an argument through words, diagrams, images, that’s part of the design process. It’s equal to the aesthetic image. So we don’t feel we’re done until we simultaneously can argue why we’re doing it and we think it’s aesthetically exceptional.

What does the architectural moment look like now? And how are you either following it or countering it?

Architecture is full of conventions, and many of them are conventions that were created for good reason and should still exist. And many of them weren’t created for good reason. So we try to go back to first principles and look at those things again. Architecture has largely become commodified. And I think that’s dangerous. My sense is that there’s a lot of architecture that’s created without a lot of thought and people are buying into the belief of conventions that actually aren’t necessarily appropriate to their project.

The Seattle Central Library

The library as an institution is no longer exclusively dedicated to the book, but as an information store where all potent forms of media — old and new — are presented equally and legibly.

There’s a whole host of things that actually don’t make sense at all. A good example is the Seattle Central Library. Seattle is a high earthquake zone and we had a big-volume building. We discovered that if we were to externalize the lateral system and divorce it from the gravity system, we actually got incredible economies. If I had just said that in the beginning of the project, everyone would have looked at me and said I was crazy. We had to slowly tease that out over time to build people to that point, to realize economies of scale. And so it’s a highly unconventional solution that makes 100% sense in its particular programmatic and physical context.

“Historically we’ve not only hired architects, but we’ve hired non architects. We’ve hired people with PhDs in Chemistry and a Master’s degree in Economics. We look for people who can think, argue and articulate their thoughts on how to impact human activity.”

You talk about bringing a sense of agency back to architecture. What do you mean by that?

Whenever I discuss this with someone, I’m always worried that we’re going to fall into the kind of trope of form versus function. I don’t want to do that. In the office we talk about performance and aesthetics are performative—for example, the St. Louis Arch. Its only purpose is to be beautiful. That’s it. It’s meant to be a signifier. So, you know, clearly aesthetics can be utilitarian. And on every project you have to calibrate classic functionality and classic aesthetics differently.

Everyone has aesthetic predilections. Our work tends to be boxy. I have intellectual reasons why we do that. Something I say jokingly, but it’s actually kind of true, is I leave the discussion of beauty between me and my therapist. I never try to discuss a project with a client based on beauty. Because it’s a subjective discussion. So I might put something before people and say, “I think it’s beautiful.” And they go, “I don’t.” What do we do with it then? We cannot advance a project on such subjective bases. If we do our jobs, we will find a solution that meets all of those specific criteria and project hurdles and that I happen to also think is beautiful. My job is to be working in the background, trying to edit all the variants, to find the one that is aesthetically compelling and which completely solves all of the project constraints. I think what happens a lot in architecture today is that the aesthetic solution is determined first, then it gets bastardized getting squeezed through the constraints.

It seems like you’re energized by constraints.

Yeah. Isn’t everybody? Isn’t every step of education about resistance? Doesn’t someone have to say “No” for you to actually think? Isn’t resistance inherent in getting stronger in everything? It’s inherent in athletics, it’s inherent in intellectual growth. If you just get to do what you want, it’s going to be very quick and the solution is going to be your first guess. Why is that interesting?

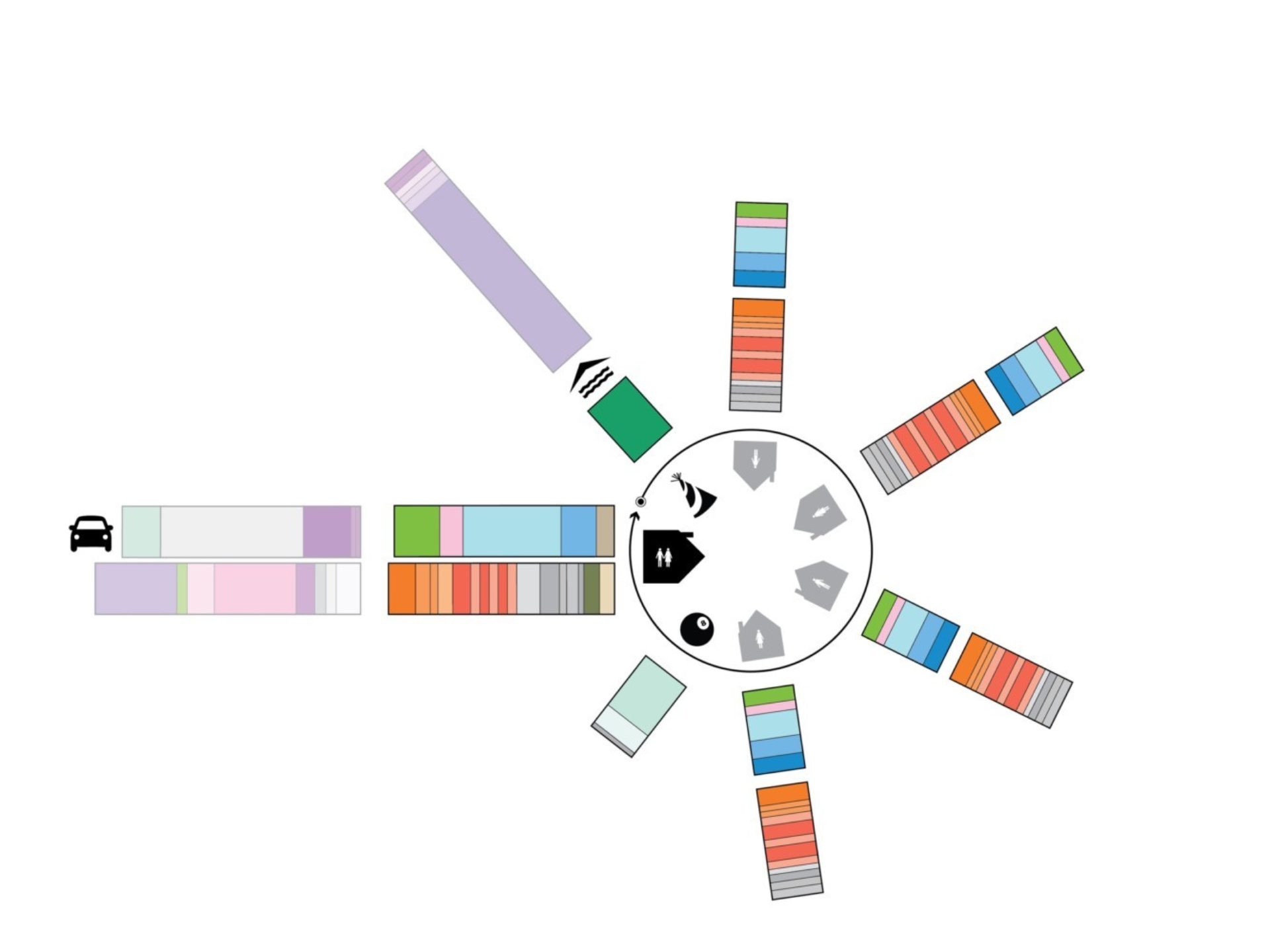

The Necklace residence. A patriarch dreams of building a family residence — “a jewel box for individual lifestyles” — in which he, his wife, his four children, and each of their four families will reside.

You design residential, commercial and institutional structures. Do you have a criteria for the projects you take on?

Good clients. Someone that’ll take educated risks. We’re always looking for projects that have some challenge. We want architecture that can do things. We’re not that interested in architecture that is only representative. And so it comes down to, are there projects where there’s something at stake? Can we invent something with the owner? Can we solve something with the owner? And that can be how you create art. It can be how you solve an economic problem.

The Dee & Charles Wyly Theatre in Dallas, TX

One of the things you said on the brief for the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre in Dallas was that you were trying to preserve freedom of movement for them to do the things they already were doing. How did you achieve that?

Something that I think has occurred in every project we do is that we think that the idea of flexibility, at least in architecture, is wildly outdated. That there is a notion of flexibility as being a kind of tabula rasa in which I can do anything I want. The two most obvious examples are theaters, those are black box spaces. And in galleries, those are white cubes. Now those things are incredibly restrictive. And so on almost every one of our projects now where we’re seeing that, to preserve certain freedoms that people have come to expect, you actually have to give them presets things that are very specifically defined. You give them to three or four or five along a spectrum, such that they can move between those presets. And they can do them without a lot of costs.

So we didn’t give the Wyly a black box. We gave them a theater that could at the push of a button transform between a true proscenium to a studio theater, sort of effectively a black box or theater in the round. Yeah. And the time and money to do that is quantifiable. So many stagehands, so many hours.

What was shocking about the Wyly Theatre is that by giving them those preset tools, it weirdly opened up their flexibility even more than we had intended. And if you look at the first 23 performances, they did them in 18 different configurations, but we only gave you four. They almost immediately started to stretch them and bastardize them and tweak them. And we’ve been doing that now in museums, and we’re doing it in libraries and we’re doing it in houses, even office buildings. You provide three or four different kinds of officing in a building, not one. It’s also how we think about sustainability. We’re trying to design future adaptive reuse into our buildings.

How do you think COVID will impact the nature of gatherings and architecture in the future?

I have two answers to that. The first way to say it is a bit of a vulgar anecdote. The current leader of the firm that did structural engineering for the World Trade Center spoke before Congress, and he was asked the question, “how do we future-proof buildings such that they can withstand airplanes flying into them?” And he looked at them, shook his head, and said exactly the right thing. He said, “the problem is not trying to figure out how to make buildings, withstand airplanes, flying into them. The only problem should be, how do we change the political environment where people don’t want to fly airplanes into buildings?”

So having given that anecdote, I hope we’re not thinking about a world in which we’re going to make it okay to have pandemics. Because I don’t really want to go to theater where there’s no energy in the room because everyone’s six feet apart. And I don’t want to have weddings that are six feet apart. And I don’t want to have dances that are six feet apart. So I would say, how about we focus on the behavior that we should all know we should be doing right now? We should be focusing on good science that would lead us to vaccines. We should be thinking about not plowing into every old growth forest. It’s all part of sustainability. Stop expanding exponentially horizontally into ecosystems that have viruses that human beings were never in contact with. That’s the big picture.

Joshua with his daughter Lilyblue in 2010

You’re a single parent of a 15 year-old daughter. How has she influenced your creativity?

I have a slightly unusual situation. Starting at the age of 7, I’ve been the primary caregiver of my daughter and a single parent. That was really right at the moment my career was taking off. I made a commitment to her, that I would be present. And that forced a kind of efficiency in working that has been embedded in the office that I think is actually really healthy. In architecture, there’s certainly the mythology that if you’re not working all the time and collapsing of sleep deprivation, you haven’t given for your art. I think it’s bullshit. Our expectation is you shouldn’t be here on the weekends and at seven o’clock, we turn the lights out.

My staff works like hell. There’s no question that this team works really, really hard. But I don’t want to know how long someone’s working. If they go home early I assume it’s because they’ve gotten done what they need to get done. It creates an environment in the studio of respect and trust and people don’t violate it. They’re exceptional. So, while this mindset started with the need to leave the office on time every every night because I was a 38 year old single father and had to pick up my daughter, it has grown into all of these other things.

This is a total non-architectural thing, but men certainly get the benefit of that. I was always treated as exceptional for just doing what women have been doing forever. And that came with certain benefits. Like, I could go to a client meeting with my child in a baby Bjorn and people would be “how amazing!” Whereas if a woman architect did that she’d be seen as not understanding professional boundaries.

Final question that I ask all my guests. How would you define beautiful thinking?

My knee jerk reaction almost sounds antithetical to everything I said: thinking without constraint. I guess I don’t mean it the same way as I would think of saying architecture with constraints. I think thinking without constraint means finding new one-off innovative solutions to constraint. It’s not being burdened by convention and ideas and history.