I’ve always been a huge fan of the talent that comes out of Cooper Union. Their interdisciplinary programs in architecture, art and engineering prepare students, for ‘making enlightened contributions to society’. Wes Rozen is a perfect example of this type of person. He applies a mental and spatial perspective of the world, to his work to make us conscious about how we move through the world.

“My dream project is to create a set of homes and a wind farm. I love the fact that you can actually be in close proximity to them in a way that you can’t really do with any other industrial-scale energy production or machinery.”

Tell me about Camber Studio and where the name came from?

The word camber has multiple meanings. One is just in sort of how you can put camber into material. At the time I was starting to imagine my own practice, I was working on a suspended sculpture project at my previous practice, and in order to get the piece to sort of fall into the correct shape, we had to build camber into the system. That kind of camber is something as a maker and designer is something that I’m always kind of looking for. I also have a deep love of airplanes and wind turbines and the shape of wings and air foils, and there’s camber in that curvature to create lift.

And I grew up around cars. My dad was a Porsche mechanic and he would talk about camber in roads and the sort of ideal curvature for maintaining speed as you go around the bend. And I also make films and these contraptions for moving cameras through space and that sort of design around motion and movement.

Camber Studio/Supersmith and Rozen residence: “We were able to expand in our warehouse space and within two months, we built out the apartment. We’re not able to put windows into the envelope of the building, so we installed several skylights to bring light into the space.”

I’ve read a couple articles on your Brooklyn studio, which you guys live in as well. Can you talk about the design and intent of that shared space?A couple of years ago, my wife and I were pregnant with our first boy. I’d been working with another practice that I started with some friends out of architecture school. But in thinking about starting a family in Brooklyn with my wife also being a business owner, we started thinking about what it meant to have children and recognizing that our current setup wasn’t going to support that lifestyle very well. Right at that time, half of the building right next to my wife’s space became available. We spoke to the building owner and asked if we could take it on as a place to build out a new studio and shop and then also an apartment so that we could run two businesses and live all under one roof. He was open to it, and within two months, we built out the apartment.

Part of the living space is also the office and then the shop is immediately in front of that. And we love it. It’s really nice to be able to just comfortably go from family life to work life in almost the same way that I enjoy going from drawing to making. There’s this natural flow that’s just so comfortable from the moment we start the day to the end of the day where even cooking activities can sort of happen in parallel to meeting with clients, emails and whatnot. So, it’s all just very seamless.

Crye Precision HQ: Crye designs and manufactures tactical gear for U.S. soldiers and U.S. allies, and it’s led by a couple of friends who also went to Cooper, They occupy an 85,000 square foot space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. They hired us to help them develop some amenity spaces for their staff. Immediately stepping into their space it was clear that they needed a a grand centerpiece to orient you to the space.

Now we have two boys who are just moving through our workspace. My wife, Natalie, and I are constantly tag teaming on taking care of the boys to taking care of work. And then also there’s a community in Natalie’s space. Her business is Supersmith, which is a shared workshop, and there are about 20 to 30 people that work out of that space at any given time. And that community is sort of an extension of our family. Our 2-year-old son who is very talkative knows many of their names, and they all know him, and he’s constantly in and out of the shop and playing with tools and taking scraps of wood and everyone loves it.

Your model is very COVID friendly without meaning to be.

Yeah. We got lucky with that.

“I started playing around with creating these forts for the boys as a weekend project. Everyone is spending a lot more time at home with their kids, and I think there’s a real market for fort systems. I may produce enough of them to send out to some friends, test to get some feedback.”

Do you two collaborate on projects?

Our home was the first big collaboration. Creating children, I would say is another big one. But the design of our apartment was something that we collaborated on, and we built it ourselves. We only had a couple of months to build out the space before our first boy was born. We quickly pulled a team together, and that was tons of fun. It was summertime, heavy construction and going for it from early in the morning until late at night every day.

We’re also starting to also look at buying some land outside of the city and looking at models that actually are pretty common in more rural areas, where people have a farm operation that’s connected to their home. We see that sort of same smooth sort of combination of work life and family life and we’re really trying to sort of bring that into an urban experience as well and be a model for that.

BAM Harvey Theater, Brooklyn | Artist: Teresita Fernandez: “We see this ivy growth up the sides of the buildings in Brooklyn. So the idea was to create this growth on the side of the building that reaches out and becomes a canopy and reflect the surrounding area. As you walk down Fulton you see the reflection of the street on this terrace. As the sun moves across the terrace through the day, just the light coming off of it animates the space.

“ Teresita created this piece to engage people to look at how people in Latin America are being displaced by climate change, drug wars and very difficult economic situations.” Title: Rising (Lynched Land) Artist: Teresita Fernandez

Have you ever practiced conventional architecture, or did you come out of Cooper Union doing something similar to what you’re doing now?

I was probably formed in the ways I am now. I started a company with three friends right out of school. While I was in college, I did internships at more conventional architecture firms and came out of that knowing I wasn’t really so interested in that type of professional pursuit. But I also don’t want to sound like I don’t have interest in the conventional. I definitely want to be doing more with what might be considered conventional architecture, taking on homes and residential spaces and developing buildings. But I would say it’d be nice to do that work with clients who are looking for a slightly different approach or sort of coming into it outside of conventional routes.

You’ve described your shop as an architectural design and film company. What’s the role of film in Camber Studio?

We started doing a lot around trying to communicate how things were built, and with that time lapse photography and documentation became a big part of our project efforts. It’s very easy to put a time lapse camera on a mount in the corner of a room and capture the activity, but it’s pretty boring. To break from the conventional time lapse documentation, we got into building cable rigs and started looking at drone photography early on.

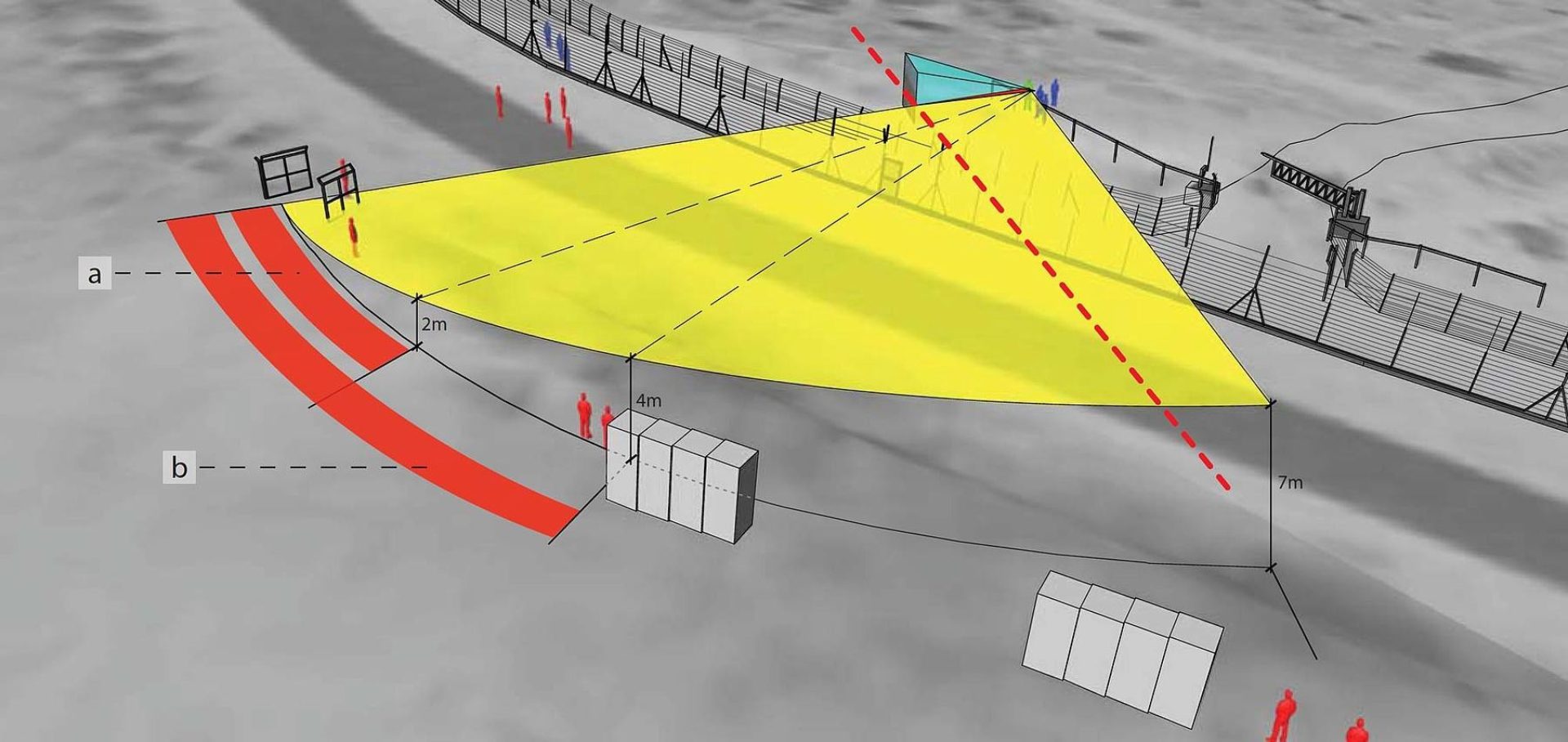

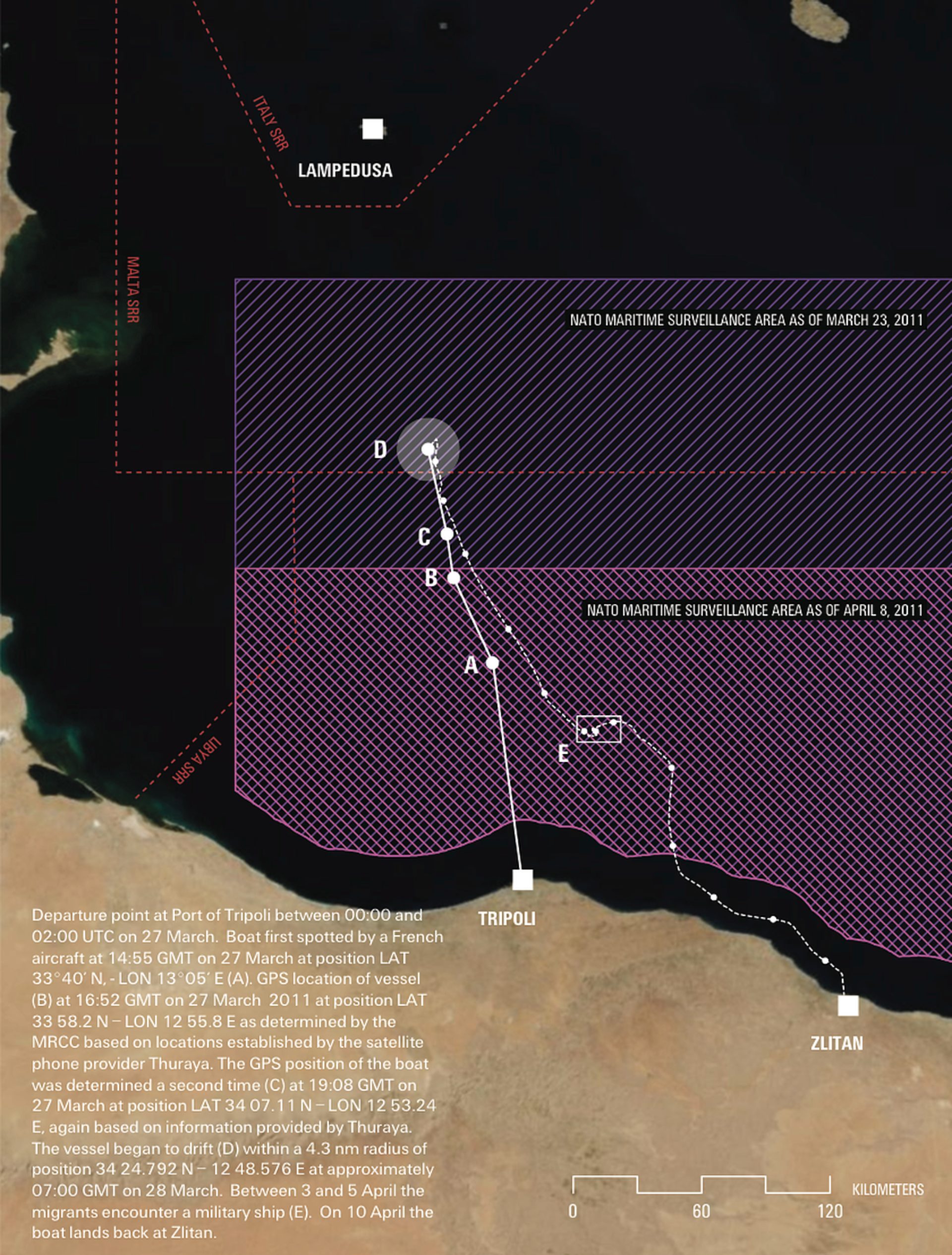

“At my former company, SITU, we were hired by human interest groups like Amnesty International to compile data from an event like a protest to build a 3D model of the event. We would work with acoustics experts or video compilation experts to overlay different bits of information to render out something that made sense of what actually happened to present in court.”

“In a lot of these cases, we would be presenting evidence against a government or a government agency as the strategy for those government agencies is often to claim that something was too chaotic. Our mandate was to quantify and render out whatever was being contested as clearly as possible so that it couldn’t be disputed.”

So, the purpose of that is to capture the process as an artform?

Yes. You get another perspective, an experience in film that you can’t experience in person. One of the most successful film projects I did was around this installation we did where we built these 20-foot-tall columns in one of the large spaces in the Brooklyn Museum. And to capture the construction work that we did there, we had this camera moving along the cable 20 feet in the air, and it ran through the space in this kind of zig-zag pattern. That video became part of the installation where people could experience the installation from 20 feet in the air.

That other dimension is something that I get excited about. I love that moment where you’re moving through a space in a way that we’re accustomed to but then you get to a wall or a window and the camera goes beyond what we could do with our bodies. And you get to experience that little extension off of your body.

You’ve talked about this idea of being driven by grand ambitions and ventures into the unknown. What does that concept mean to you?

I think it’s just breaking from convention. It’s trying to find those opportunities that are between categories, between different modes of experience or practice. It’s finding those opportunities where a lot of communication happens. That space between two people, that space between a person and the space that they inhabit, between science and art, between making and drawing. It’s that is its own between where things can really take off.

Wes and Natalie met at Cooper Union where she was studying painting and he was studying architecture. Wes runs Camber Studio and Natalie runs Supersmith where artists can share workspace and a retail storefront.

That seems to be kind of a guiding principle for your work. Where in your life did that come from?

Two things immediately come to mind. I moved around a lot when I was a kid. I lived in … I think it was like 15 homes from when I was born to when I headed to college, in five different states. My mom was very nomadic. With that movement I had to sort of place myself and kind of figure out who I was between those different areas and between different groups of friends and schools. And then I also went to Cooper which broke from convention. I found poetry and art and architecture and even engineering there. After five years of studying architecture there, I was really encouraged to sort of find that space between. I think that really sort of got into my bones.

You like to force collaboration across disciplines. What are some of the more interesting cross discipline projects you’ve worked on?

I go back to some of the research work I did in my first practice out of school when I was working with some other people from Cooper. We worked with human rights groups like Amnesty International to do forensic work where we would analyze videos, audio recordings of protests or other sort of events where human rights were challenged. We’d create a three-dimensional model of the city and then render vectors of tear gas or bullets. Then we would use tools architects use for buildings every day to help render a spatial understanding of what took place in an otherwise very chaotic scene. These renderings would be used as evidence in court.

Was that meant to be in addition or as a counter to evidence in the case?In a lot of these cases, we would be presenting evidence against a government or a government agency. The strategy for those government agencies is often to claim that a scene was too chaotic or that there wasn’t concrete evidence around something. So, our mandate really was to quantify and render out whatever was being contested as clearly as possible so that it couldn’t be disputed.

You collaborate regularly with the artist, Teresita Fernandez. How did that begin?

Teresita is a great artist that I’ve been working with for close to 10 years at this point. She was one of a handful of artists that we did fabrication work with at my old company. When I made the move, she wanted to come with me, and I had been handling most of her projects before. She keeps us busy. One project goes right into the next, which is great for building up a new practice and having that consistency. But also, Teresita is lot of fun to work with. There’s a lot of mutual respect. She’ll have a sketch or flash of an idea and reach out and say, “Hey Wes, how about this? How about that?” And then we’ll immediately jump into collaborative design work and engineering.

Her Solarium project, for example, is something we did last summer, and we just finished a big project for a show that opened in November. She looked at how people in Latin America are being displaced by climate change and very difficult economic situations and even things like drug wars and other sort of things that are really sort of wreaking havoc in the Latin America world. We created this large palm tree out of copper that’s going to be suspended into space as the sort of centerpiece. And then we’re working on another project, inspired by living in New York and Brooklyn where we see this ivy growth up the side of buildings all the time. The idea was to create this growth on the side of the Bam Harvey Theater that sort of reaches out and becomes a canopy and reflects the surrounding area.

What’s your dream project?

That’s easy. I want to create a set of homes and a wind farm. I think wind energy and the turbines that are operating on an industrial scale are awesome and I love the fact that you can actually be in close proximity to them in a way that you can’t really do with any other industrial scale energy production or machinery. I’d love to design homes that are within a wind farm where you can sort of read the landscape through the turbines, understand something that’s invisible, the wind passing through the landscape just through the speed of rotation of the turbines and the orientation.

Would the homes be fully wind powered?

For sure. Most large wind turbines can power an entire town. It’d just be taking a little bit of the energy that they’re producing to power a home. That’s certainly part of it, but I think it’s the spatial aspect I’m excited about.

Would the homes be small? Those wind turbines are massive.

I know. I can imagine cabins where people who share a similar joy in wind farms could rent. Maybe it’s an artist residency or something along those lines. There’s lots of different ways to integrate. Do you put the home right at the base? That could be pretty intense with the sound and shadow patterns. You could create different conditions throughout the landscape. It could also be framed as a project to better understand wind energy and draw the public in to have an experience in wind farming. A lot of people have driven past them and see them from a distance or see them in the commercial. But it would be cool to actually spend a night in a wind farm, or a summer.

Very cool. So, creating an environment for people to have understanding and affinity for something invisible.

Yeah.

One last question: how would you define beautiful thinking?

It’s when you think outside of yourself. It’s when people truly let go of themselves and step into producing something for another person or occupying that space where they’re fragile, but they are letting themselves fall into an experience that’s maybe out of their comfort zone. But they’re embracing it, whatever it is, whatever that experience may yield. They trust that it’s going to work out. So great film, great architecture, great art. It encourages people to sort of get out of their comfort zones and share something.