When I first discovered The Great Discontent six years ago it was a large, thick, perfect bound magazine. I had never seen anything like it. The design was spare, but the interviews, photography and art all had such depth. I became intrigued by Hugh — who he was, why the design couple who started the magazine sold it to him recently, and what his plans were. After we spoke, it was easy to understand why Hugh was chosen to carry the torch.

“When we map our our relationships of influence and networks, they look like beautiful seeded out dandelions. if you start to do the multiplication, if there are 120 roughly people in your social network and they all have 120 and they all have 120, we’re talking about thousands of people that arguably will influence everything from your life expectancy to your job prospects.”

I’m excited to hear about your plans for The Great Discontent, but first want to step back and ask: how and when did you fall in love with creativity?

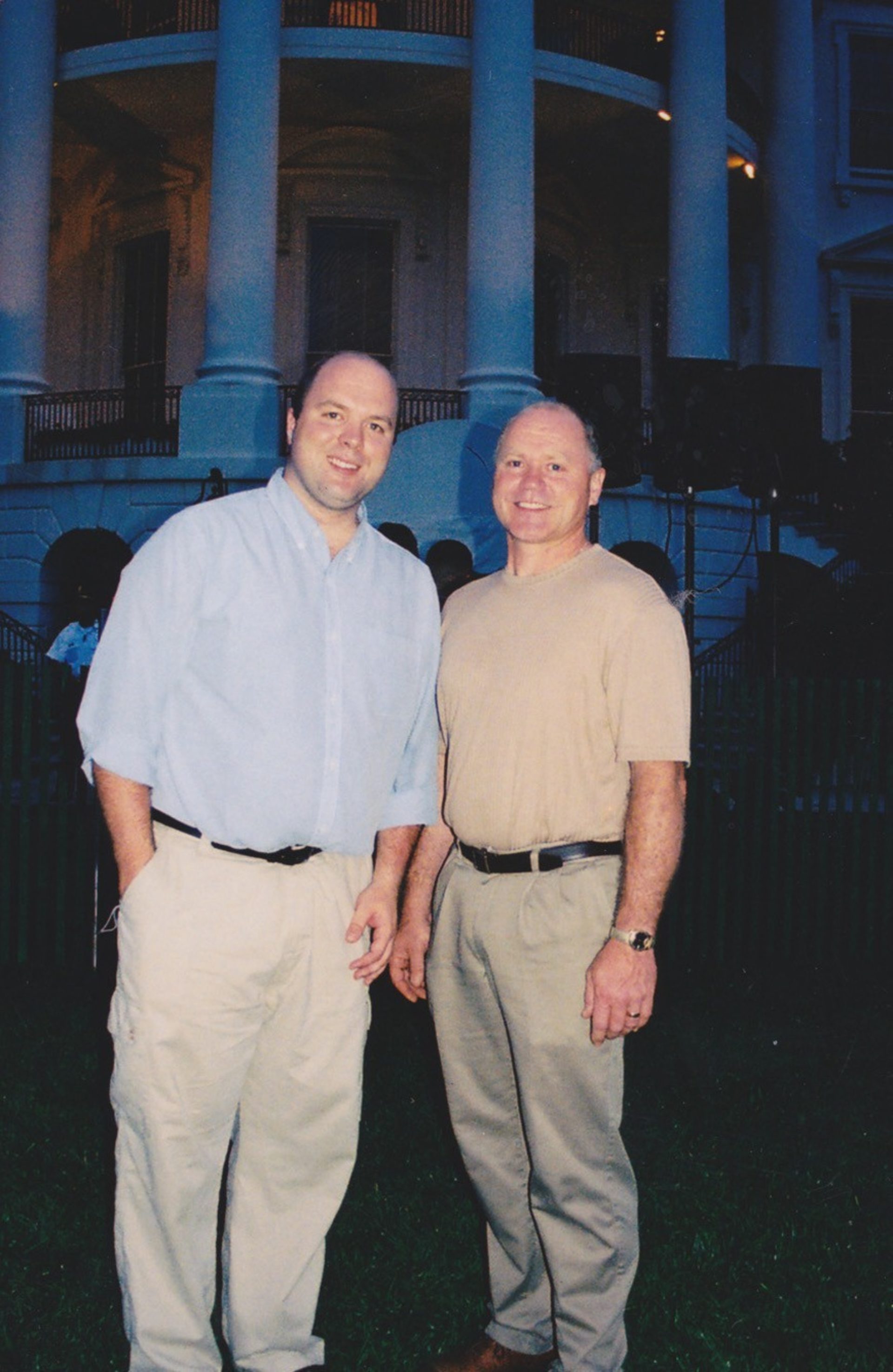

Wow, fantastic question, and important for my origin story. I wasn’t “the creative kid” in my family. My younger brother was the artist, and I was much more structured in my approach to the world. When I was 28, I was sitting on the White House lawn with my dad on the 4th of July — sounds romantic, but it led to a very visceral realization. My dad was a small-town electrician who left a very tangible sense of legacy in the small towns I grew up in. And in that moment, I recognized, not only did I not have a legacy — as a political consultant and community organizer I’d left division in my wake. So right then I made the decision to leave a career that had been as much my personal identity as my profession. It took a couple years, but I came back to the Midwest, to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It was here I rediscovered creativity and the role it had played throughout my life.

Hugh with his Dad, July 4th, Washington DC, 2004. “I wasn’t the creative kid in my family. My younger brother Luke was the artist, drawer, doodler and I was much more structured in the way I approached the world.”

When I arrived back home, I saw a group of storytellers, filmmakers, designers, illustrators and writers. They’d been going about their lives for ten years, focusing on the arts to create cultural context in the community — yet they were in fact seen as lazy, or living lives of luxury. Not only was that a misdiagnosis of the role creativity plays in our lives — it was undervaluing society’s key bridge builders and community weavers.

This season of discovery of my own creative expression coincided with my daughter being born. Faced with new life, which ultimately ties to mortality, I found myself exploring things that I never would have considered as a young adult.

“My 10-year old daughter Emerson is actively and naturally engaged and asks questions that strip away the hubris and the adultness of this work in a way that is really enlightening.”

Can you talk about the role of creativity when it doesn’t manifest itself in a piece of “art?”

I’m on a mission to awaken creativity in people who’ve not been trained as artists.

That was core to my work with OTA, the nonprofit that emerged to dismiss the notion that creativity was a leisure activity — that in reality, it was fundamentally what it means to be human.

I looked around this region that I thought I knew so well with new eyes and saw extraordinary creativity. Both from people who self-identified as creative professionals, and those who didn’t yet see a role for creativity in their work. When in fact, to survive on the plains, as indigenous or immigrant pioneers, through the winters and the droughts, is an exercise in human ingenuity. Truly an act of creativity.

The Great Discontent started in 2011 as a web only magazine but then published their first full sized print version in 2014.

Focusing on beginnings, creativity, and risk, The Great Discontent provides a memorable look into the lives of its subjects via long-form interviews

One of the heartbreaking moments of that transition period for me was when I visited my extended family. As I was walking up to their home, I saw this incredible piece of folk art, a welded piece done in really kind of rough edged way but that had clearly been given great care. It could have been sitting in a gallery in D.C., or New York, or LA. When I said, “You know, it’s incredible that you collected this piece. Is it someone from the region?” I was told, “That’s your grandfather’s.” It was at this moment that I recognized that the man I had seen as so practical, but — and I judge myself deeply for this — so limited, had been fruitful as a farmer and father and grandfather — but also as an artist! Now I spend an awful lot of time celebrating artists and creatives not too different from him.

My “thinking spot” is a small oasis about 10 blocks from my home in the center of Sioux Falls, SD”

You’ve obviously lived in bigger markets — how much of your work is trying to celebrate off-the-beaten-path creatives versus those in urban centers?

My desire is to work with the untold stories of creatives and artists and makers and storytellers wherever they live. There is a great deal of joy for me to elevate creativity in unexpected places. I think places like Indianapolis, Cleveland, Denver and Albuquerque are somehow seen as being on a different tier. It’s hierarchical by nature. But, my heart is in those in-between spaces.

It’s wonderful that you’re not only defending these spaces, but you’re promoting them and seeing the beauty that comes from them.

I appreciate that. In 2019 I was able to visit 40 cities focused entirely on the design community of those cities. I sit on the national board of AIGA, which is the professional association for design. Much like many associations and membership-based entities, we in the last decade have been challenged by declining membership. The task was to explore ways to add value and identify trends in those communities. What I found was that at some high level, creative expression, especially amongst professionals and design, had developed this sameness in the work that’s being done throughout the country.

Left: Workshop in Bentonville, AR, 2019 | Right: Design workshop in LA, 2019

I could fly into most cities of a certain size, assuming they have an airport, take a shuttle to a nondescript hotel, eat a meal at a nondescript restaurant, hold a meeting somewhere and leave and have a sense of sameness. But the second you step off, literally in some cases, one step off that well-worn path, the local character and culture of design is extraordinary. It’s thriving in less expected places where there’s a dialect and vernacular amongst designers in places like Albuquerque and San Antonio and Asheville, which are often shadowed by larger cities. Yet, it’s those cities that are doing something wholly original, built out of persistence.

“OTA was a nonprofit that was around for about 10 years. We raised a few million dollars through grants and partners. We did micro documentary films and brought 150 influential creative professionals across disciplines to the region. The entire focus was to say this is not a leisure activity as much as it is fundamentally human.” Images from a filmcollaboration between Passenger and OTA”

So, I can’t agree more that places like Indianapolis are doing work that matches or exceeds work we’re seeing anywhere. I think that is actually in spite of the internet — digital media and ubiquitous inspiration has created that layer of sameness. It’s self-reliance and isolation, to a degree, and lack of expectation that creates uniqueness.

Did you find out why there was a drop in membership?

The themes that emerged as I was visiting these cities, and places like LA and Miami, was a deep desire for belonging. Belonging is a critical building block of community. It comes through trust and psychological safety and elements of identity. The second big theme deeply tied to that is proximity, which is about intimacy and understanding, creating those pathways to belonging. Then the third pillar was this idea of influence not being about power, but actually being about reciprocity. When we join a community, whether it’s geographic or virtual, we have the ability to influence how it lives and exists in the world.

One thing I’m trying to poke at is the idea of lateral thinking. Why don’t people in finance talk to chefs and why don’t people in law talk to choreographers? There’s so much learning that can happen across those sectors. When you were spending time with the communities, were you seeing an appetite for this?

The appetite is human. It’s definitely deeper amongst those that identify as creative by nature or by profession, but I think it’s a human instinct. AIGA, Design Observer and The Great Discontent are cross-disciplinary by nature. I don’t identify as a designer. Unless there’s ink on my hands, I don’t identify as a creative. “Creative” is a word that makes some designers bristle but is more inclusive of all the different types of creativity.

The AIGA chapters who were thriving were able to tap into something beyond their core group, find people who didn’t identify as creative professionals. If there aren’t bridges for ideas and pathways for people to come into and also depart the boundaries of a community, creativity and innovation will start to wane and dissipate in a way that’s not productive.

Yesterday, it was announced that you will also become Managing Director of Design Observer. How will these two platforms work together?

Theoretically, these things ultimately need each other. The Great Discontent speaks to upcoming young creatives who need to understand how to navigate their creative journeys. Then you have more senior executives who engage with Design Observer and want to question the implications of their approach to work so they can move large scale systems, businesses, governments, and the planet in a different direction. These are part of the same set of spectrums. They’re at different scales with different participants, but they’re absolutely critical and related to each other.

This is a group of creatives that are going to create artifacts. As I’ve said before in AIGA context, they’re going to make the brochure for the bait and tackle shop, but they’re also going to stay up late that night and start to figure out how we can address things like climate change. That excites me in a way I can’t possibly explain. It taps into those visceral desires and inspirations that I had at the White House when I was a kid, and now it’s in a space where I actually believe I’m working with people capable enough and willing to actually solve the problems.

Hugh with Tina and Ryan Essmaker (founders of The Great Discontent) at OTA 2014.

How do you see The Great Discontent evolving?

I come to The Great Discontent as a sincere, committed and infatuated fan of the site. I went back and figured out that interview #20 was the first interview I read. And there are now over 300. I come to it as a fan, but I also see responsibility to the wider community. That doesn’t mean that we won’t tell the stories of a designer that has created a beautiful body of work or has experienced personal challenges within the structure of their career or creative journey. Nor does it mean that everyone needs to enter creative work with a desire to address global challenges. But, I’ll say somewhat cavalierly, not everyone needs to be featured by The Great Discontent either. With the limited number of untold stories that I will be fortunate to share with the remainder of my time here, I’d like to tell stories that address deeper issues through incredible creative people that are doing truly, truly extraordinary things wherever they choose to reside.

Designer and 6th grader, Zykera Tucker, in Washington DC discusses programming to address health and safety issues in her community with Hugh.

We just finished our first interview and photo shoot with designer Zykera Tucker. She works on the south side of D.C. She is challenged by the systems around her relative to education. She is challenged by deep issues like gun violence and food insecurity. Yet she’s designing spaces for collaboration at the neighborhood level. She’s assisting in the design of programming to address things like gun violence. She is creating products that are in my mind, incredibly sophisticated and — I’ll just say, she’s not exactly the type of designer you’d expect to be featured by a significant creative platform. [Editor’s Note: this interview will be published March 3.]

Too often, scale is perceived to only come through breadth and reach and impressions and numbers. We’re going to switch axes for a little while and focus on depth.

Hugh at Design Observer Conference at MIT in 2018.

Are there any other plans you have for The Great Discontent, especially with your new news about Design Observer?

We’re looking at what it will take to bring TGD into communities at the local level. For example, we might come to Indianapolis for three or four days. We’d interview two or three creatives and do their photo shoots, then do a live event where we interview a fourth. And that becomes a podcast and a month’s worth of feature content, a deep dive in Indianapolis to create a fuller sense of place.

Design Observer is in a similar exploration about how to go deeper. It has started doing an extraordinary event the last two years that’s capped at 300 people. It is intimate. It is conversational. It’s influential in terms of the people on the stage — executives like the CEO of PepsiCo and the Chief Creative Officer of Target — but just as importantly, maybe even more impressively, in terms of the audience, which contains a similar caliber of individual. It becomes this incredible momentary collision of ideas across industry and across geography, through a kind of cross disciplinary lens of how design sees the world. There’s a lot of creative professionals looking inward at their profession, their process — and that’s important — but it’s when design looks out at the rest of the world that it’s transformative.

“Your creative quality is influenced by who influences you and how they influence each other.”

You have a very different definition of ROI. Can you explain how you define it?

ROI is “Relationships of Influence.” We are influenced by the important people in our lives, and they affect our prospects, as well as our inclination to take creative risks, or to smoke, or to gain weight — we involve them in our lives professionally, personally, physically and even spiritually. There is so much data showing how deeply they influence us, and we can map those relationships.

If you are a creative, your creative quality is impacted and influenced by who influences you: your stream of new ideas, your field of view, the scope of the world, your ability to make uncommon connections — it’s all influenced by that group. Wouldn’t you want to know who they are? Wouldn’t you want to have a sense of who those people explicitly are, so that you can invest in them deeply or expand or change that group?

I’ve done the exercise on myself in front of a group at a workshop. I said I wanted to be healthier. I wanted to be more physically active. We mapped it out and recognized that literally no one in the 10 names I wrote down work out or eat discernibly healthy. So, there is no one to hold me accountable when I go out to meals with these individuals. There’s no one to say, “Do you really need a second dessert?” There’s no one to say, “Let’s go for a walk instead of doing a sit-down meeting.” And so, to recognize that moment and to begin then to identify people who aren’t in that core group, then bring them into that circle with intentionality — that’s an important part of the process.

Understanding network theory is critical to creating awareness and ultimately change. We know that if someone knows the basic terminology and structures of a network — meaning they understand bonds and bridges, nodes and edges, some really 101 level stuff — then there’s a 75% higher likelihood they’ll be promoted over the remainder of their career.

Wow, regardless of industry?

Regardless of profession. They did a control group in a leadership program in Chicago and half of them got some basic training in network theory and half of them didn’t. Is it full causality? No, but are the implications dramatic? Sure.

I was reading something a couple weeks ago on LinkedIn where they had identified the number one thing employers were looking for is creativity.

Executives recognize in 2020 that the only truth that they can hold onto is that they will exist in an environment of uncertainty. Unless they surround themselves with resilient people who exhibit ingenuity and adaptation to change, and ability to solve complex problems, they won’t stand a chance.

You’ve got a lot on your plate now. How does it feel?

I am not known as a terribly content person, by my family, past colleagues or anyone that’s crossed paths with me. So, there’s something joy-filled about owning a brand like The Great Discontent. Two days ago, when we announced Design Observer appointment, I woke up the next morning and the only word that came to mind was “contentment.” On a personal level, it was moving and emotional. On a professional level, I think was the recognition that in this moment I’ve stepped into a space that forty years of exploration has created: a unique moment, where being resilient to uncertainty; recognizing the incredible importance of connection; and being someone who can serve as a bit of a guide in that conversation — these are the moments that we find out what we were made for. Waking up yesterday morning was one of those moments. It doesn’t mean that it will be forever, but for now, I’m absolutely overjoyed to be in conversations and at tables like this one, with people who are incredibly talented and have a much broader perspective of what the world is, and what our role is in it.