I met Luke last year during a course we both took together. I immediately gravitated to his quiet demeanor and his precision of thought. He is a classically trained guitarist and composer who manages contemporary classical musicians. When I heard one of his artists, Emily, who was a harpist, I knew she would be perfect for Eunoia. The harp is a heavenly instrument and Emily’s music is equally so. Born as a midwesterner in Kansas, Emily now resides and practices in Sydney, Australia.

“I took my Celtic harp out to a cliff overlooking the Blue Mountains last year after we’d had the devastating bush fires. I just felt the need to go and play for the animals that lost their lives and the trees that were trying to regenerate and all of the little insects that are trying to make it in this new landscape.”

Emily, tell me about your origins and your evolution as an artist.

EG: I grew up in the suburbs of Kansas City, Missouri. Music has always been a big part of my family, but I had no idea what a harp was. It wasn’t until I was 10 years old that I heard the harp on a CD of Celtic music. And I just knew at that moment, I have to be able to do that. Like, there was just something about the sound. It really resonated with me. And so for a whole year, I begged my parents to let me learn how to play it. I told my orchestra teacher that I was going to be playing a harp in the orchestra next year. And she just laughed at me. When I showed up for the first day of orchestra in seventh grade with a Celtic harp, that was it.

Left: Emily with her first harp in 2001. Right: Emily’s debut at Carnegie Hall in 2010

I found a lovely teacher in Kansas City. She was a freelance harpist who played lots of weddings and events. And I remember showing up for my very first harp lesson and walking into her home. Her entire first floor was filled with harps, all of these Celtic harps and all of these big golden pedal harps as well. I remember the feeling of just sitting down and pulling the harp back on my shoulder and just knowing that I was going to spend the rest of my life dedicated to playing this beautiful instrument. I know it’s quite a ridiculous romantic story, but I swear to you, that’s how it happened.

When did you find other people like you who were passionate about classical music?

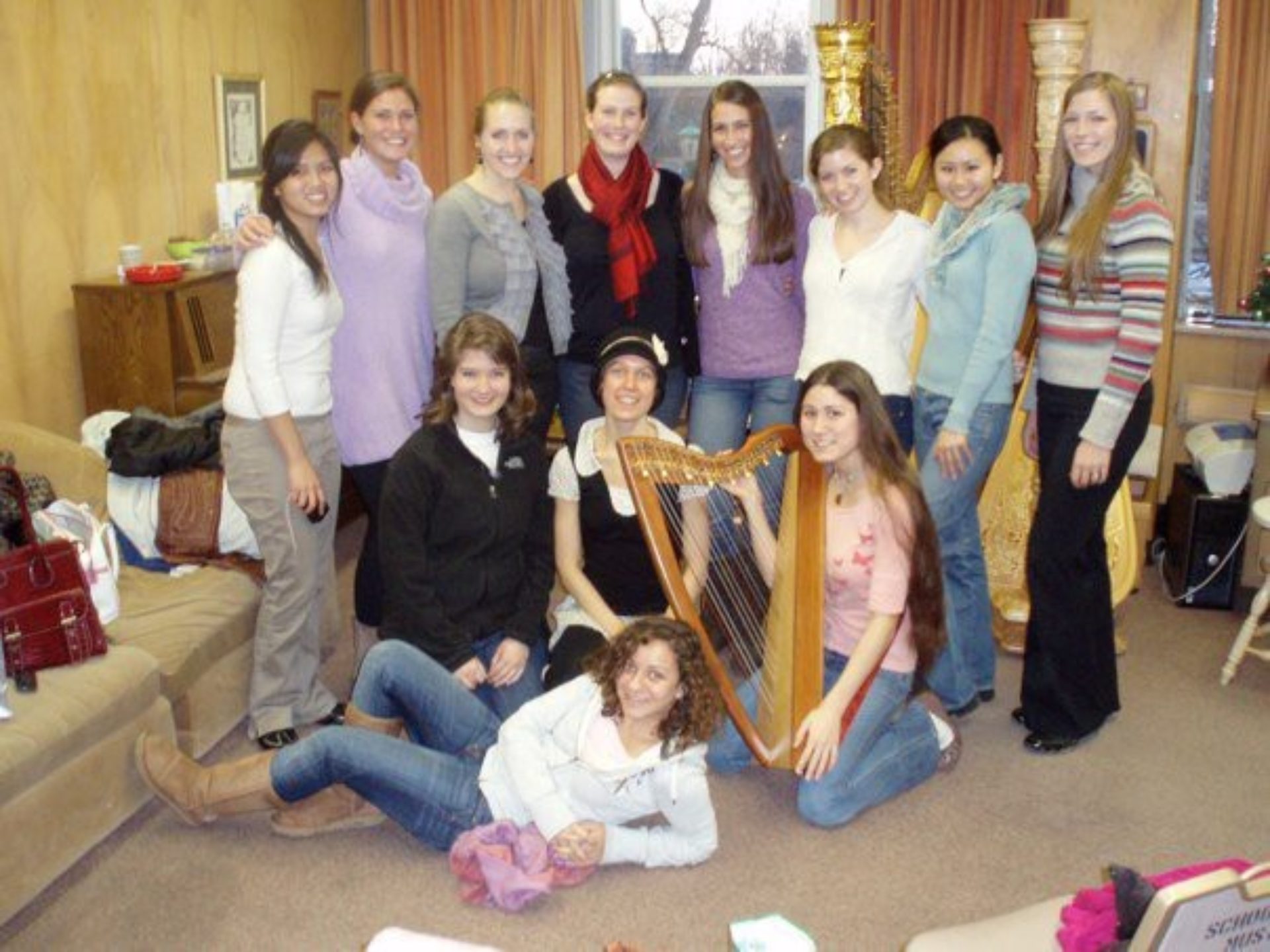

EG: It was hard growing up in the Midwest, where classical music is not a big thing. I got bullied and made fun of for playing the harp because it was so ridiculous. And that just made me bury myself into music even more. I was lucky to be able to go away to summer camps, especially one called Interlochen up in Northern Michigan. That was the first time that I was really surrounded by all of these other kids that were just as passionate about music as I was. And that was a huge turning point for me. Then from there I went to Indiana University in Bloomington, which has one of the best music schools in the world. And that was also incredible because I got to study with Susann McDonald, who is like the godmother of harp. She’s taught everyone. I was in a studio of 20 other harp majors, if you can believe it.

Up until then, I didn’t really have anybody to compete with in Missouri. When I went to IU, it was like I was just another harpist. There were all of these amazing students that were competing in international competitions and winning them. And, you know, I was just this girl from Missouri, just trying to keep up. That definitely pushed me and just gave me a good perspective on how hard I needed to work in this industry.

And then you moved to Chicago?

EG: Yes, I did my master’s at the Chicago College of Performing Arts. I went there because I wanted to study with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s principal harpist, Sarah Bullen. I was able to really hone in on my skills of trying to become an orchestral harpist. I studied with Sarah for four years, and I stayed there as the principal harpist of the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, which is the training orchestra for the Chicago Symphony. I got to work with all of these amazing conductors, and all of my colleagues came from all over the US. I stayed in Chicago for two years after that freelancing, and I was lucky enough to play with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was there that I met three amazing harpist colleagues and founded the Chicago Harp Quartet, which was and still is an integral part of my career.

Left: Emily at the harp studio at Indiana University 2008 Right: Emily playing with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2013

How did you end up in Australia? I’m assuming there’s a boy involved.

EG: Of course. There always is, isn’t there? Through my studies, I met so many amazing people. And one of those people was a composer that I met while studying at Indiana. He was from Sydney. Fast forward a few years later when I was in Chicago, he came up for a conference and asked if he could crash on my couch for a few nights. He had another musician with him who was a recorder player from Sydney. They both stayed on my couch for a few nights. We really hit it off playing these ancient instruments, but also having love for contemporary music, living music. And the recorder player said kind of off the cuff, “You’ve got to come down to Australia sometime and we can perform together,” and I laughed it off thinking like, “Oh yeah, right. That’s never going to happen.” But it did. She won this massive award a few years later and was able to bring me from Chicago to Sydney for a six-week tour, culminating in a recital at the Sydney Opera House. And I was like, “Yes, of course, I’m going to do this.” She commissioned three new works for harp and recorder, and we got to work closely with those three composers, one of which is now my fiancé. So that’s how I ended up here. Love and new music.

Do you feel like the classical music scene is different there than it is in the Midwest?

EG: Yes and no. I mean, Sydney is a big city for sure. There’s a lot going on. But there’s also a lot going on in the Midwest as well. And as musicians, we’re just inherently creative and restless and creating opportunities and making things happen. So, I think it’s just knowing where to look.

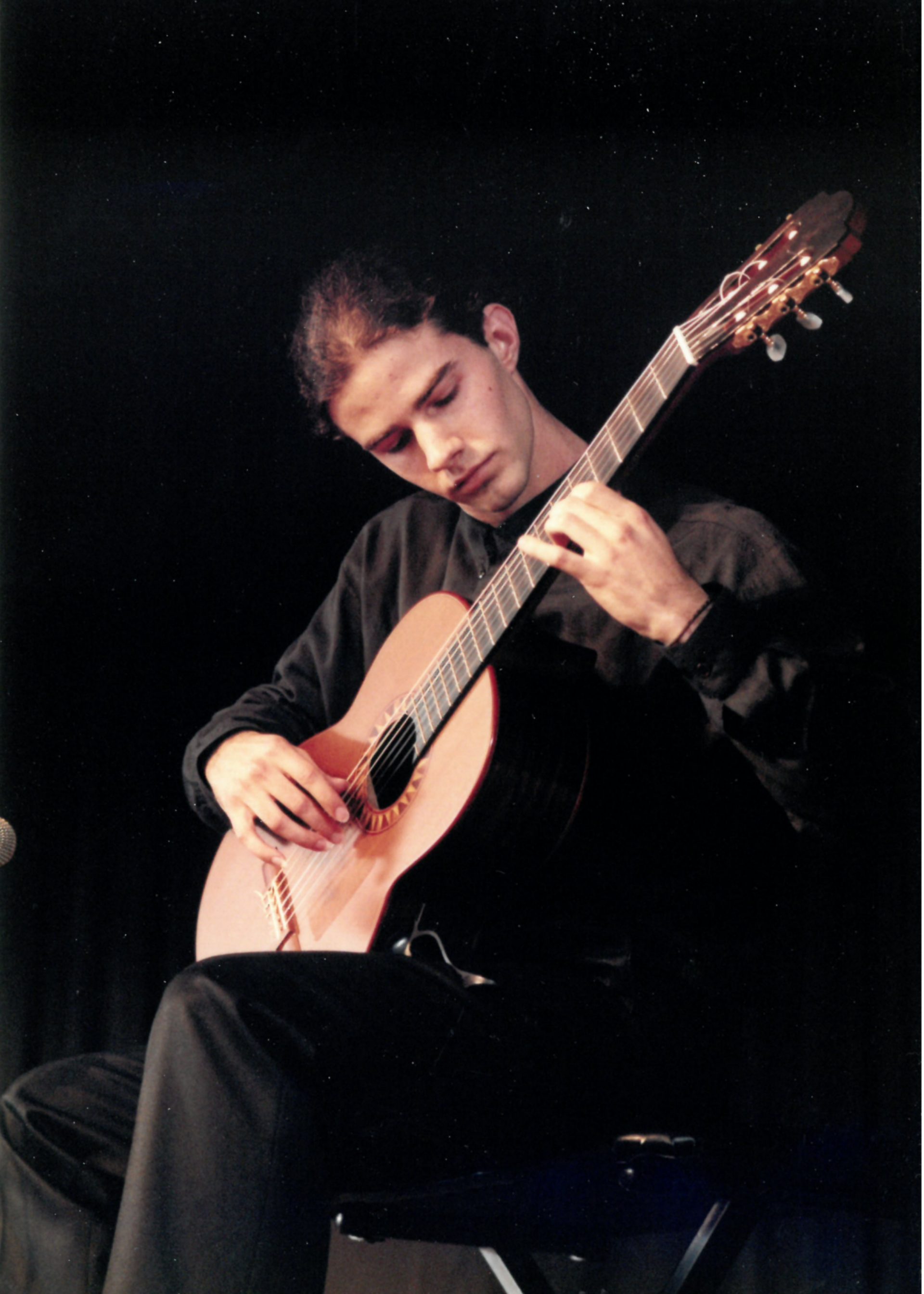

Luke, in 1995. “I’ve always had a strong connection to contemporary music or music of living composers. That comes from my own background as a guitarist and composer with a strong interest in that music. It’s an area that I’m passionate about so when I was putting together the roster, I was naturally inclining towards those sorts of artists,”

How did you meet Luke?

EG: Last year I went to the Banff Center for Arts and Creativity, this amazing campus in Canada. I got accepted to go and spend five weeks there in the middle of winter. I was able just to lock myself up in the mountains, which I love, and just practice. While I was there, I met a classical guitarist named Andrew Blanch, who is also based in Sydney, and we really hit it off as friends and as colleagues. It was a really special time. We were all incredibly vulnerable because everyone was working on projects, nothing was finished. We had these sessions every week where we sat around in a circle, and we would play for each other and we’d play works in progress, and then we would talk about it. Andrew and I were actually some of the only traditional classical musicians. We started playing together while we were there, finding all of this repertoire for classical guitar and harp. And in conversations with Andrew, he just started talking about this Luke and telling me all of these great things that Luke was doing for him as his manager. Being an independent, classical artist is a small business, and I’m doing it all by myself. I’ve known for a while that I needed help. And when he started to tell me about all of these things that Luke was helping him do, I was like “you’ve got to put me in touch with him.” Luke and I met in January of this year, and I think it’s just been an incredible relationship. I am so grateful to have him in my life.

Emily and Andrew practice at her home in Sydney.

Luke, what did you think when you first heard Emily play?

LT: I think when hearing an artist, the obvious thing to go to is the sounds that they’re making. We’re in a privileged position in classical music, in that those who come through the system whether it’s with an orchestra or an ensemble, or as a freelance musician, the artistry is really superb. The voice that I’m looking for is the person behind those sounds and the stories that they have to tell. So when I first met Emily, what really came forward is that she was an artist who cared deeply about what she did. She knew what sort of music she wanted to make and who she wanted to make it with. And she had ideas about the steps to get there. That’s what I need as an artist manager to work with someone that has goals and is willing to put in the work, because it is a lot of work outside of the practice room to build a career.

Would you have ever put Emily and Andrew together?

LT: Guitar and harp is something I don’t think I even knew existed before I had heard Andrew say he was working with Emily. So yeah, that’s definitely something I hadn’t come across before.

Emily catches up with her mom after a performance in Chicago

The harp is one of the oldest instruments — it’s about 3000 years old. Do you feel like you have hit the edges of what sound you can get from the harp, Emily?

EG: Not at all. I think it’s going to be a lifelong journey exploring sound and space, and a beautiful thing about the harp is the resonance, right? You pluck a string and the entire instrument just lights up and resonates and you can feel it on your body vibrating. It’s an incredible experience to play with that in time and space and explore different ways of phrasing and different ways of thinking about playing the harp. Like once you pluck the string, that’s kind of it, but it’s where you place the next note and listening to the decay of the sound as well. It’s an incredible thing. So I’m still exploring new colors and approaches and I think I always will be.

Tier 1 represents several artists who play different instruments. What is the common connection between them?

LT: One thing that’s come about, I guess through my relationships, is a strong connection to contemporary music, or music of living composers. And that comes from my own background as a guitarist and composer with a strong interest in that music. A lot of the people I’ve connected with through the decades in the industry have been people working in that space. It’s an area I’m passionate about. So when I was putting together the roster, I was naturally inclined towards those sorts of artists.

Classical music is finding a new audience on places like Spotify. A third of the people streaming classical music last year were 18 to 25 years old. Why do you think that’s happening?

LT: The modern playlist movement as I’d call it, is the next generation of radio. A lot more listeners are moving over to streaming and listening to music through playlists for certain tasks. And there’s nothing more reliable than classical music to maintain a certain mood. The absence of voice in a lot of classical music is going to make it easier to have on in the background. So there’s a lot of people listening to classical music right now who are using it as background music. And that’s great in some ways, but it’s also difficult for people working in the industry because someone that listens to classical music in the background is not necessarily the same person that’s going to go out and listen to a specific artist on Spotify or go out and see a concert by a classical musician. So that’s one of the challenges we’re facing with rising audiences, but perhaps not the sort of audience that is going to support careers.

You and Emily have been doing some interesting things with social media while on performing hiatus from the pandemic. How do you think social media is going to change the relationship between listener and artist going forward?

LT: With a streaming platform, there is not really the chance for classical musicians to build relationships with audiences. People only connect with a mood or an interpretation, depending on their level of experience with the music. But in social media, we can reach out to people that we would have no way of getting in front of otherwise and show them ourselves and how we look as we perform. And if connections are made beyond that, we can be communicating with audiences, telling them more about us, and getting to know more about them. One example of this is the guitar and harp piece that Andrew and Emily played that we posted on social media. People hadn’t heard that combination before, and yet they really enjoyed that. So that’s great feedback to have, and we would have had none of that over this period if we hadn’t reached out to people through social media.

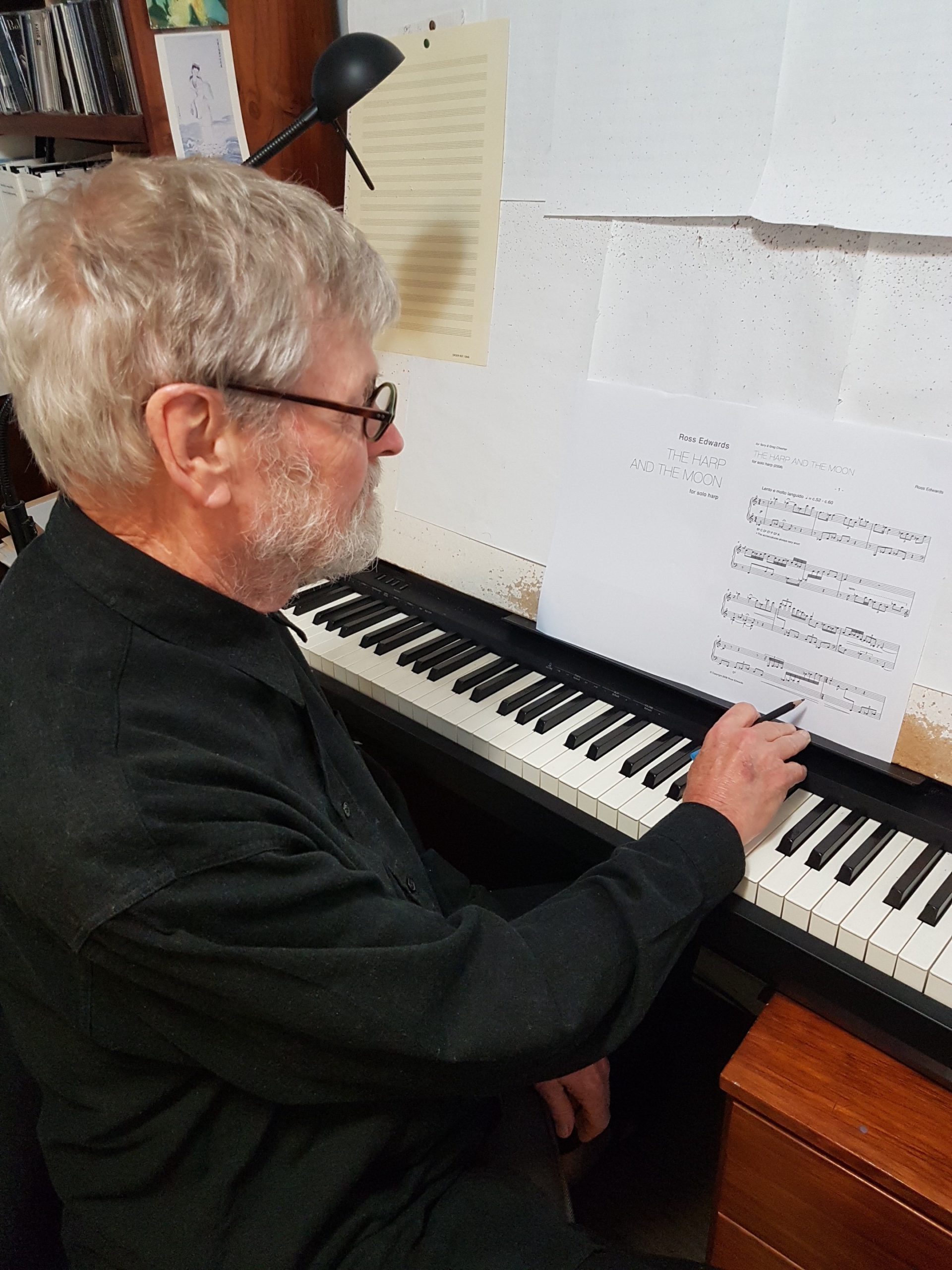

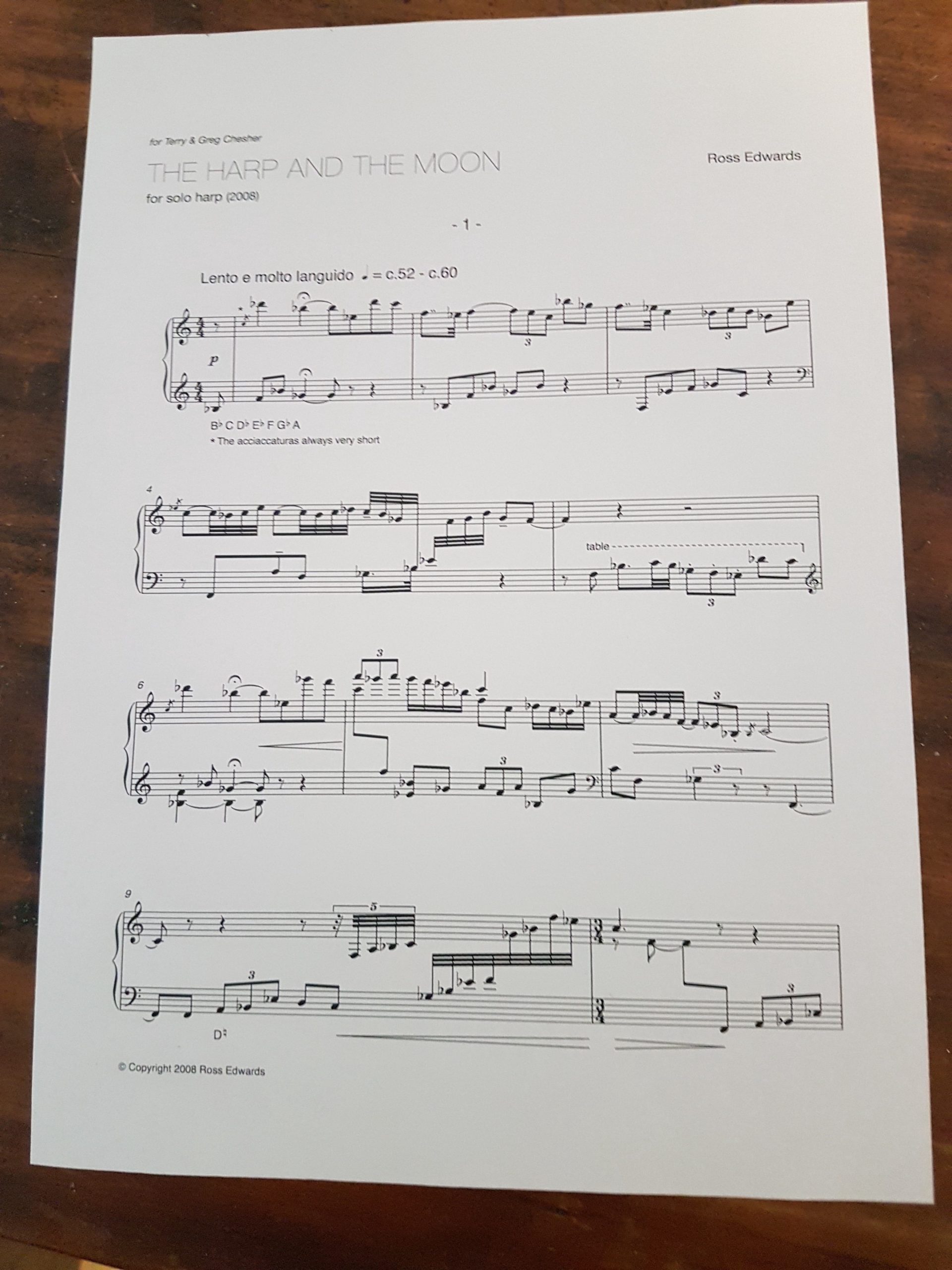

Left: Composer Ross Edwards with his piece, “The Harp and the Moon .“ | “I’ve spent the better part of a year working on this incredible piece of music. Many people have played it before me but it feels like it’s my own. It’s my favorite thing to play at the moment.”

Emily, you are a star on social media. You seem to genuinely enjoy connecting. How has it been for you not being able to play on a stage for the past seven months?

EG: I’ve definitely used social media as my outlet. I love being on stage and sharing my music with people, and because I haven’t been able to do that Luke and I have been able to move things around and change how I do that in the traditional sense and channel those efforts through social media. So we’ve been creating and recording all of these new videos that I’ve been able to share and put out there and it’s been really fun. At first it was kind of terrifying because I hadn’t really done that much before. It’s different than playing a concert because people are just getting a really close look at my face and my hands and exactly what I’m doing. And it’s going to be out there on the internet forever.

But now your parents can see you play.

EG: Yeah. I love that.

Have you enjoyed sort of bringing a new generation into the genre? That has to be rewarding.

EG: Definitely. One of my main aspirations in life is to shed light on the harp, to put the spotlight on this instrument that doesn’t get a lot of airplay. It’s not well known in most households, so to be able to share that and reach people that wouldn’t normally see a solo harpist is incredibly special.

Luke, what do you think is most misunderstood about classical music?

LT: I think in terms of the work that we’re doing the most common misunderstanding is that classical music involves some distance from performers. Historically audiences don’t have close access to performers, they’re just used to seeing someone up on a stage. They’ll applaud at the end, but they don’t expect to have a connection with that artist beyond that performance. Particularly in the orchestral setting, the orchestras will bring through major international artists season after season, but they’re not connecting with performers in the long-term besides that base of the orchestra. I think a lot of enjoyment in music and art comes from knowing the people who are creating the art, understanding why they make the art like they do. And it’s possible for people to have that relationship with performers. There aren’t a lot of classical musicians that are doing that right now. And that’s what we’re trying to do, to build connections with audiences so that they know us. If you don’t understand the artist, then you don’t understand the music as well as you might.

One more question I’ll ask both of you: how would you define beautiful thinking?

EG: Beautiful thinking is the ability to actually transcend thinking, finding that space where you’re riding above thought and actually able to exist on this whole other plane.

LT: A large part of the training of a musician is this idea of mastery. You practice hours and hours a day, day after day, year after year. And what you’re aiming for is a control of the physical, to the point where you can follow where your intellect takes you. But then as you get better and better, you get out of the way and follow what you’ve built into your muscle memory. And for me, it’s creative. The flow state is where beautiful thinking happens in music and in much of life.