Beautiful Thinkers exist in all walks of life — science, business, culture and the arts. Whether you’re Pat Brown , the founder of Impossible Foods who’s solving one of the world’s biggest environmental problems, or Katherine Gray, an artist who creates conceptual works of art from blowing glass, they’re both manifestations of beautiful thinking. Beautiful thinking can be a process, a moment, or an action that changes how we perceive the world in the biggest, or smallest, of ways. In the case of Katherine’s work, we see how she is attracted to the polarities of glass, how it’s clear and opaque, how it can be fine art in some forms and invisible in others, and how even in craft arts, which tend to be viewed as more feminine, glass blowing is typically male-dominated.

Insights happen at the intersections of these disciplines. Businesses would benefit from studying the arts. They’d learn craft, nuance and the visceral power of image, color, form and texture. Katherine doesn’t make pretty objects, she gives us a lens to view the world through the magical lens of glass. She’s an artist, a professor and the head resident evaluator on Netflix’s series, “Blown Away.”

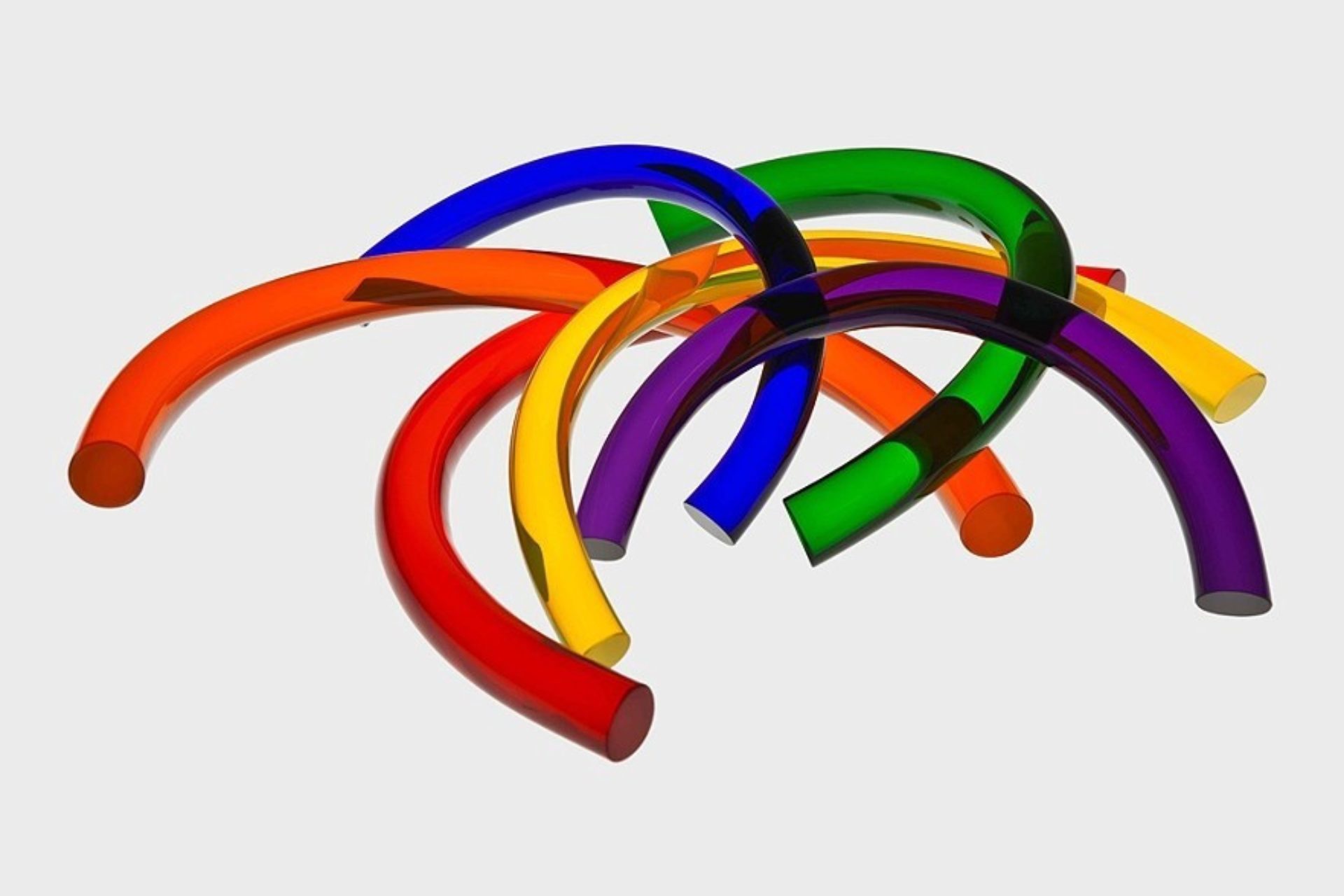

Katherine pushes the boundaries of glass with her installations, often incorporating light and colored shadows that come from the rainbow. These rainbows are also the bridge she uses to bring us into her world through her art.

I’m fascinated with what you’ve said about playing with the polarities of glass. You’ve said before, “I see many more analogies within glass, it’s incarnations, its histories, its properties, that have relevance to larger issues in the world.” Can you expand on that?

On a more basic level, it’s the idea of transparency. Glass is certainly a material that’s associated with being transparent. That’s one of the really unique characteristics about it. It’s something that I think we take for granted. At the time, the piece I was making was kind of referring to transparency in the political sphere, and how it’s something we just assume is there until it’s not. And then we realize, “Oh wait a minute, what was that? Where did it go?”

The idea that glass was clear and colorless really only came to be valued during the Renaissance and afterwards. Before that, glass was made to look like other materials, like different kinds of rock. At the time of the Renaissance, followed by the Enlightenment of culture and society and big advances in the sciences, they came to appreciate the colorlessness and clearness. So I kind of associate that idea with enlightenment.

Katherine working in her studio at the Chrysler Museum of Art Photo credit: Echard Wheeler

Did glassblowing start in Italy during the Renaissance?

There’s apocryphal stories about how glassblowing actually was discovered. It’s attributed to the Romans trying to cover clay with a hot glass, making what’s called a core formed vessel — casing spongy clay core with glass and digging the clay out afterwards. The theory is that one time they were doing that and the clay wasn’t sufficiently dry. And as it was encased in the glass, that moisture started to evaporate and expand and cause the glass to bubble out from the central core. So Romans really invented probably 80 to 90 percent of what we know about blown glass.

And then it really isn’t until the time of the Renaissance in Venice when there’s this blossoming appreciation for glass. Glassmakers could marry into nobility, they were so highly respected in society. The glass maker skills were highly prized. Under the guise of wanting to make Venice safe from all the glass furnaces, they moved all the glass makers to an island called Murano, and that’s still a glass making island today.

“I love being a glassblower. The thing I’m missing the most right now with quarantine is not being able to blow glass.”

“Broken Bow” Photo credit: Fredrik Nilsen

I’ve read that the formulas for glass making used to be kept a secret, and the penalty was death. What is it about glass making that has this shroud around it?

Some of those secrets and techniques are hard-won and take a lot to figure out and discover, and some of that still exists in the glass world in Venice. It’s definitely not as bad as it once was, but was pretty ingrained for a long, long time. What you figured out, you kind of kept to yourself, and that was your cash cow.

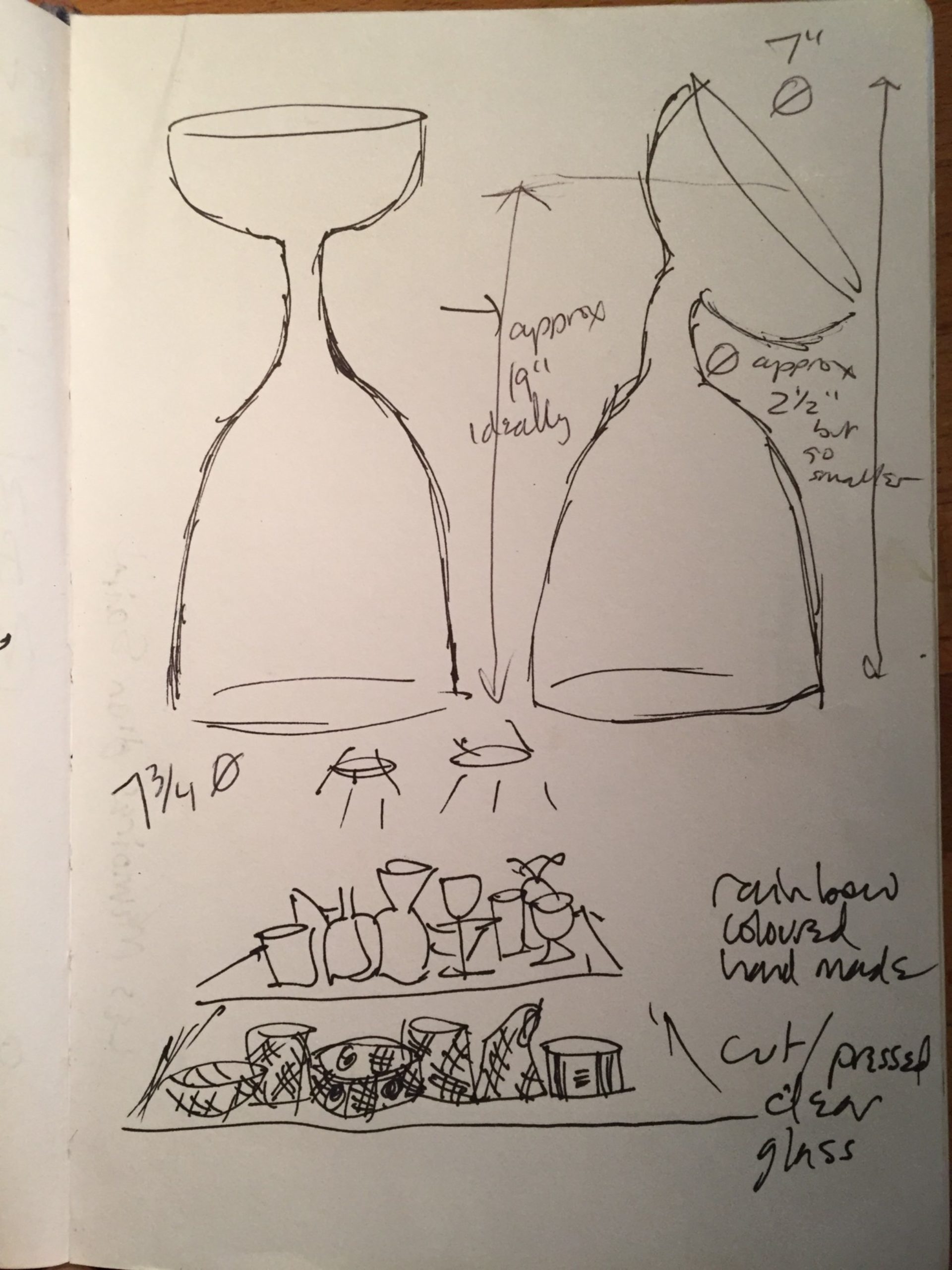

From Katherine’s sketchbook showing the beginnings a the scent diffusing bottles series

“A Rainbow Like You” Blown glass, acrylic, lighting 2015 Photo credit: Fredrik Nilsen

What got you into glass?

When I was an undergrad at art school in Toronto, I wandered into the glass studio at my school. I had thought I wanted to design lighting and furniture, and so I thought taking a glass course would be helpful for that. So I took the course, and I loved it, and I kept taking it. I think I maybe made one light and one table. I quickly abandoned the more design, functional aspect and went more toward sculptural, unique art pieces, which worked out well. I go back and forth, but I’m probably still better known for sculptural work.

“Black Oil Slick Entity” Blown Glass 2017 Photo Credit: Andrew K. Thompson

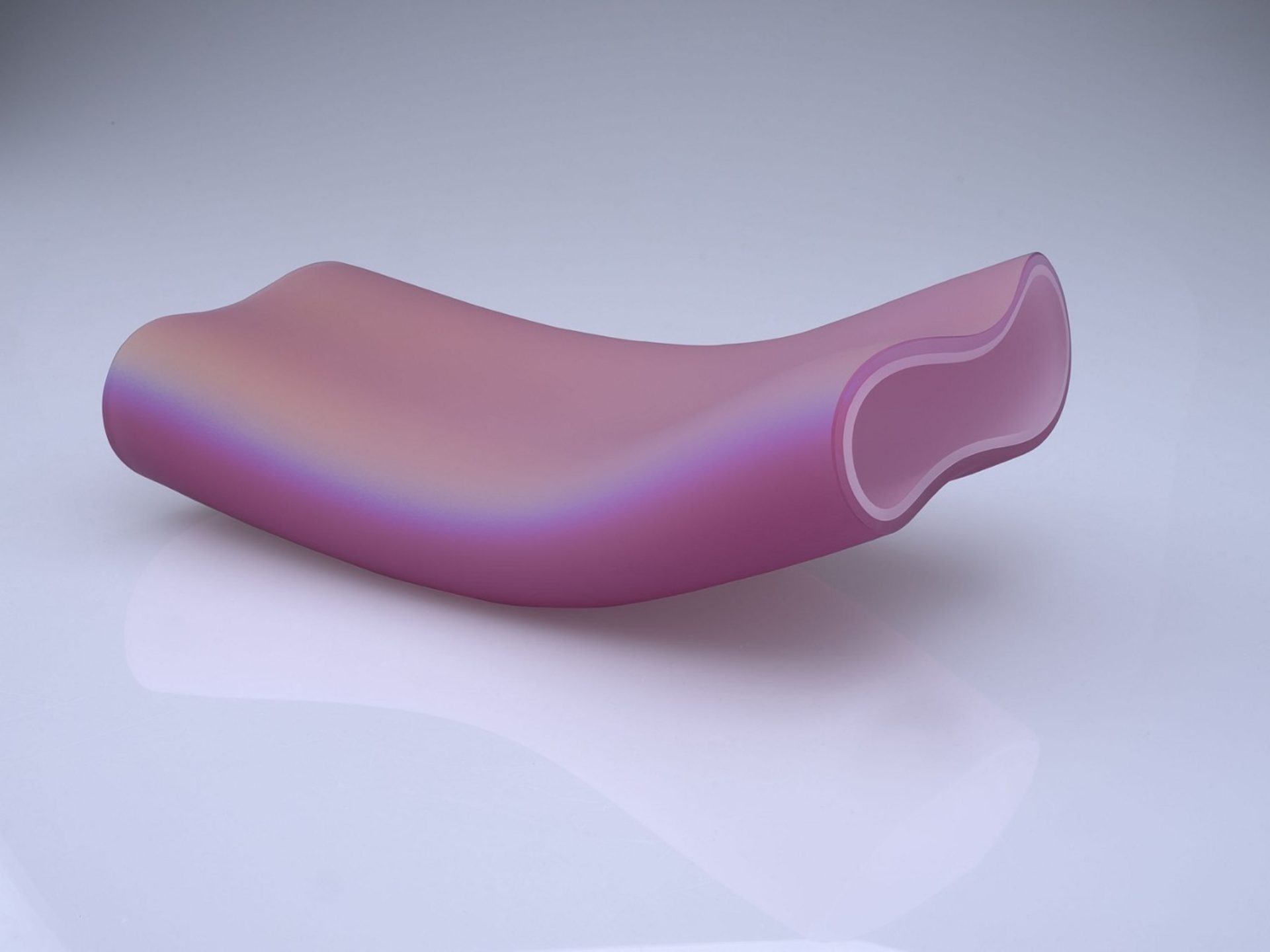

“Pink Sleeve” 2020 with iridescent coating using a technique from NASA’s rocket windows. Photo Credit: Andrew K. Thompson

I saw a demonstration video of yours and the process seems super athletic and highly dangerous — at any moment the piece could break. What percentage do you expect to fall or crack in your work?

Oh gosh, a high percentage. A lot can go wrong at any time. As you get better and more used to it, that happens less and less. But still, even the best glass blowers can still have a bad day and everything ends up on the floor. It makes you really appreciate when something works out well.

“Forest Glass” pre-existing glass, acrylic and steel shelving, 2009. Photo courtesy of The Chrysler Museum

“Fallen Tree”, handblown glass, 2009

You turned functional glass objects into trees and sculptures, but you also repurposed things to make a chandelier. Tell me a little about the concept behind that.

I want to elevate domestic glassware. And it’s taken me a long time to realize why I keep coming back to that. I know as a kid, we had Corning, like Pyrex mixing bowls in the kitchen that my mom would use, a measuring cup and stuff like that. In some ways, I feel like the domestic sphere gets underrepresented in culture, in the high art world even, and sometimes wonder if that’s because it’s so associated with being in the feminine field.

There is a bit of implicit bias against craft materials in the art world. But I wouldn’t say it’s hard and fast. There’s definitely some great artists that use craft materials and great craftspeople that make amazing art. So there is some overlap there, but glass is a bit more complicated because it is pretty traditionally a craft material, but one that’s been traditionally male-dominated. And so that’s a bit enigmatic I think because most craft materials often get associated with women’s work.

That’s a nice tension.

Yeah. I’m trying to play off of a lot of polarities there between usage of material and the sphere it exists in, who makes it, who uses it, who values it, and trying to point out some of the inequalities.

From Top to Bottom Right: “Wonder Sandwich Serving Tray”, “Wonder Sandwich Nesting Bowls” “Wonder Flowers”

“I found it fascinating that the word wonder is so closely associated with this bland, nutritionally bereft bread product. They call the red, yellow and blue dots “wonder balloons” in their graphic identity and when I think of balloons, I think of blowing glass.”

I loved the pieces in your series about Wonder Bread. Was part of your aim to elevate junky pop culture?

Yeah, I was definitely trying to elevate something that seems lowbrow. The idea of the word “wonder” was a big inspiration — the state of awe and wonder about the world is something as an artist you want to maintain and aspire to. That’s the thing that gets drummed out of us as we grow up. But I also found it fascinating that the word is so closely associated with this pretty bland, nutritionally bereft bread product. But they call the red, yellow and blue dots “wonder balloons” in their graphic identity and when I think of balloons, I think of blowing glass. So you said it correctly. I’m trying to bridge this gap between high and low brow pursuits.

Some of your work is in the Corning Museum of Glass. I had no idea that a brand known for casserole dishes was elevating glass as an artform. Is this recent?

That’s been their mission for a long time. Five years ago or so, they opened a giant new wing to display contemporary glass art. They’ve got an amazing science wing that talks about the role of glass and optics and telescopes and stuff.

Most people probably don’t realize, but Corning is also behind the technology for the glass on smartphones. Touch screens. So a big part of their company is the industrial application of glass.

Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York

The Art + Design wing at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York. The brand associated with vintage glassware is invested in promoting the industrial and creative uses for glass, including screens on the iPhone.

A body of work that makes reference to the experience of being a glassblower, or being in a glassblowing studio.

You hired a perfumer to create a scent for your exhibition “This Makes Me Think of That.” What role do the senses play in your work?

I turned 50 a few years ago, and started thinking about the day when I wouldn’t be blowing glass anymore. There’s a few smells you experience when you’re blowing glass that are really particular. It crossed my mind that it would be cool to smell the smell again. Then it started to occur to me that I could use scent and sounds and some other sensations to create the feeling of being in a hot shop for people who would never have that experience.

I made a sound piece by attaching little contact mics to some of the glass blowing tools — tweezers, things that look like scissors, stuff like that. When I was making a little drinking glass, you would hear the sound of these tools interacting with the glass, like cutting through it or tapping on it. The idea was that you were kind of eavesdropping on this intimate conversation between the tools and the material.

“Hearth Half-Life” from the “Hearth” series

From the “Hearth” series: Clear Uranium glass becomes tinted under UV light

There was another piece where you used glass and UV light to display vibrant bright colors. What was the thinking behind that?

I was making these stylized hearths and campfires, thinking about the warmth you feel when you’re sitting around a fire and how warm you are in the hot shop when you’re blowing glass. So that particular one I made with uranium glass. So just under regular light, it looks like clear frosted glass or colorless. And then under UV lights, the uranium fluoresces. So then you see the bright orange and green and purple, whatever the tints of uranium glass in there.

Talk a little bit about the show on Netflix, Blown Away, and how that happened.

A lot of us in the glass world were really skeptical and surprised when this production company reached out saying they wanted to film this competitive glass blowing show. The glass community in particular was really nervous because (on) a lot of those reality shows, people are nasty and they scream at each other and there’s a villain and all that. And that’s not really what the community is about. But they said, “No no no, we don’t want it to be like that. The drama is just going to be in the glass blowing.” They assuaged my fears, and I think they made a great show. The contestants were amazing. I was super psyched that it was as popular as it was.

I know you’ve said the format of the show was a little challenging because glass blowing can take a long time.

Yeah, yeah. That’s a whole other factor. Most of the time when people are conceptualizing to fabricating to finishing an actual artwork takes days, weeks, months, sometimes years. And in this instance they had six hours or something.

While the glass blowers are working, I’ll walk around and talk to them individually, kind of like a Tim Gunn character from Project Runway.”

When you’re teaching at CalState, what are some of the things you’re teaching, and what sort of things are you learning from your students?

I always find the students really inspiring because they don’t know what you can and can’t do yet. So they always have amazing ideas, and sometimes it’s kind of heartbreaking when you know what’s doomed for failure. But students have to learn this stuff. It’s not going to be very satisfying if you just tell them, “No, that’s not going to work.” They need to see it themselves. In that experimentation is where some amazing things happen.

Last question. How would you define beautiful thinking?

I think it’s inspired thinking. And to me, the time where you’re just about to fall asleep, or if you do yoga, and you’re coming into corpse pose at the end and your mind is just emptied out, and all this stuff can percolate and cross-pollinate. That is my favorite thinking time because it’s always productive, but always surprising.