Jax Kordes and Ayrianna Jones

"What's the one thing you can say about every person that is on the same branch of your family tree that came before? You don't know if they could speak, you don't know if they could walk or talk—but they had sex." Dr. Bryant Paul

Dr. Bryant Paul is a Media School Professor who has worked at Indiana for 22 years. He explores how technology shapes sexuality, intimacy, and communication. He's spent nearly 30 years studying the psychological and social effects of sexual media.

Transcript:

Carolyn Hadlock:

Today we're talking with Dr. Bryant Paul. Bryant has spent over two decades studying how digital media transforms human sexuality and intimacy. He's a faculty affiliate at the Kinsey Institute, and his work has been cited by the U.S. Supreme Court. Welcome to the show, Bryant.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Thanks so much for having me.

Jax Kordes:

Bryant, can you talk a little bit about your work and how it relates to our manifesto?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

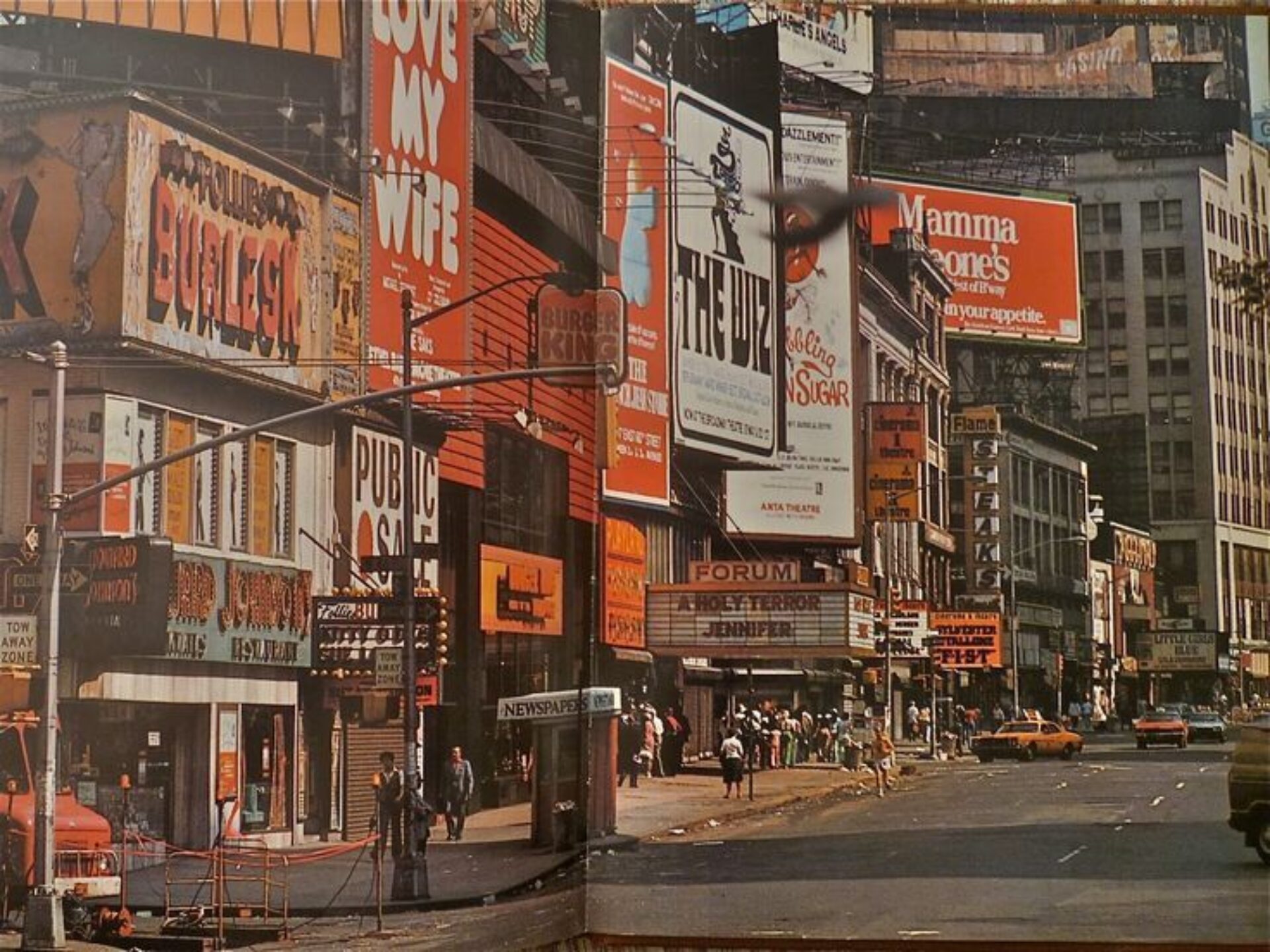

Yeah, well, I've been studying the social and psychological effects of sexual communication for close to 30 years now. As your manifesto explains, it has evolved over time. It started out with being interested in the effects of pornography, honestly. That drew me in. In the late '90s and early 2000s, a lot of research was done on the impact of sexually oriented businesses—strip clubs and adult bookstores—because cities were trying to close them down based on what they called "negative secondary effects." These were effects not related directly to the business, but supposedly brought crime in or lowered property values.

For years, the courts had assumed that was a reasonable assumption. We ended up looking at all the data they had collected, and it wasn't the case at all. If there was any evidence, it actually suggested that these places were beneficial to most of the neighborhoods they moved into—probably because they don't move into residential neighborhoods, they move into business areas that are usually economically depressed.

Once I got to IU and began doing my graduate work, I became very interested in how technology, particularly online technology, was changing things. I'm actually kind of lucky—or made for this kind of research—in that I'm a Gen Xer, so I'm a rare breed. As I was growing up, the transition to digital occurred, so I know both sides. I know how to use a rotary phone and how it works, which most people know one or the other.

I was really interested in this notion that there's this desperate craving, especially when you hit puberty, and these mixed messages saying both "yeah, it's desirable, it's something..." but also "here it is, we can use it to sell things, we can use it to get people to do things, we can use it to get people's attention."

It created a compartmentalization of the notion of a craving that is the foundation of humanity. What's the one thing you can say about every person on the same branch of your family tree that came before? You don't know if they could speak, you don't know if they could walk, you don't know if they could talk—but they had sex.

I'll talk about this more later, but it's such a fundamental thing. We're carrying around in our skulls the same brains that cavemen and cavewomen carried around in theirs. We are not built for the mediated environment that we exist in now—at all, cognitively. That became sort of the foundational position from which I started studying this stuff: How does the caveman brain process today's mediated environment? And it's just not working out particularly well in a lot of cases.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Yeah, evolution's not happening.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Right. Evolution—I mean, it is happening, but it doesn't happen during a generation. We're using a dated computing system, in essence, a processing system, to live in a world that, in large part with our more base instincts, doesn't make a lot of sense. We don't have a media detection mechanism in our brains, so we have to develop that. We have to learn that. That's why media literacy becomes so important.

I mean, it's literally teaching people—we teach people to read, we teach them to do math, we teach them to speak foreign languages, but we don't teach them the one thing we do the most, which is communicate through media.

The scariest thing I can hear is "I know it's not real." When they say "I know it's not real," I always think, "Oh, you do?" But there's so much... The fact that you're watching it means that you're still incorporating it. For instance, if you watch Love Island or Love Is Blind, all these popular programs—you might say "oh, that's not what real relationships are like"—but it does have an impact on how much you should be kissing, how interested in sex you should be, what the basis of a relationship is supposed to be about. Those subtexts are what we incorporate into our scripts.

Ayrianna Jones:

So you talked about the effects of media programming. Is it intentional for the people in charge of these organizations and technology to create these kinds of conversations around these types of desires?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

That's a great question. Yes, of course. I mean—look, the marketing industry, the entertainment industry—it's an industry that, in essence, is trying to rent your attention. They're giving you content that gets your attention and then doing a kind of bait and switch.

One of the things that's really interesting—I don't want to say troubling, but interesting—is that in recent years, because of the siloing that's taken place, you can watch politics that's only in your lane. You can watch content that is only interesting to you.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Like an echo chamber.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Absolutely. Yeah, the media echo chamber. I've kind of started to think—it used to be there was a mass medium, there were mass media. I don't know if there are anymore.

Carolyn Hadlock:

It's all splintered.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Everybody has their own media ecosystem. So when we say "let's do a survey of a thousand people," well, who cares, right? We can kind of get an idea of where they're coming from, but everybody has such a different experience now. The idea of the mass media was that everybody kind of had the same experience, at least generally. And now the only sameness is that we're all having a different experience.

Carolyn Hadlock:

That's fascinating.

Jax Kordes:

Especially nowadays with social media. A lot of their systems have algorithms, and those algorithms are based on the accounts you're following, the type of content you're engaging with. So it's definitely a different experience for everyone, and it's not really something that can be measured in the same way, like you were saying, like a survey.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah, I think you're absolutely right about that. I think there are ways of studying it, it's just gotten a lot harder. When you study it from a psychological perspective in social science, we talk about what are known as "individual differences."

Carolyn Hadlock:

Like tribes.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Absolutely. Or you can do it by socioeconomic status, you can do it by interests, hobbies, you can do it by age, you can do it by fetishes. If you're talking about sex and sexuality, you can talk about sexual preferences. So you can group those people. That's really what marketing has become—public relations and advertising have become about breaking audiences into micro-audiences. The only thing you really need is a big enough micro-audience with enough money to be worth giving them some attention.

Carolyn Hadlock:

As you mentioned Jax, the algorithm creates a fabricated reality. It's not really real, but it feels very real.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

It reinforces your preexisting expectations. That's why—I mean, we talk about kids—it's so important to step in. I've become of the mind, and I wasn't like this early on when social media became a thing, but no kid needs to be on social media before 16, even 18. We see an increasing number of college students that say "I hate social media." And then you say, "Well, do you use it?" "Yeah, I have to. How else am I going to...?"

But I've had parents tell me, "Well, I can't keep them off TikTok. I mean, they'll fall behind their friends." I'm like, "That's the stupidest thing I've ever heard." Let them—they won't fall behind. They'll jump in front.

Carolyn Hadlock:

And if they see things that they shouldn't be seeing.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

And that's the other thing—you think you have control because you're moderating what you think they're seeing. But again, those subtexts... Yeah, even if you're moderating, I've watched things with my kids and afterwards thought—woken up in the middle of the night and thought, "Wait, that wasn't a great message. I need to talk to them about that tomorrow."

I've got some training in this area, and I try to tell people you really have to counter-program your kids' media experiences. We love negative information. We love to hate it. It's one of those things where, especially in politics for instance, if you get information not about how great the person or the people or the side that you support is, but how terrible the others are, that actually lights up your pleasure centers in the same way—and often more—than hearing how great the positions of those you follow are.

Think about it for a second: if you're walking down the street and on one side there's a burning building, on the other side there's a bucolic field with bunnies and deer, which one should you pay attention to?

Carolyn Hadlock:

Yeah. Isn't that the limbic system, though?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah, absolutely. It's what kept us alive. People don't realize that every thought you have, every cognition you have in the neocortex—that information has to pass through the limbic system. So nearly all information that you experience, that you process, is already tainted with an emotion. And we get some juice out of it, we get some positive feelings. Some dopamine is released—not to oversimplify, because that term is completely overused and misused—but we feel good about avoiding danger.

Why are scary movies pleasant? Why do people like scary movies? Why do we like true crime? It's horrible what happened to those people—but we feel maybe that we're less likely to fall victim to it. We see that justice was served, the crime was solved, so we feel a little bit safer.

We are much more prone to pay attention to—in fact, in essence, if you think about our nervous systems, they're kind of negative information detection mechanisms. What is the thing that could hurt us? We only really learn and advance, and as you talked about in your manifesto, evolve culturally and individually, if we are calm, if we have time to give thoughts and cognition to our better angels. And keeping us in a complete state of panic all the time is the media's job.

We've talked about this extensively in a lot of our classes here in the Media School—the notion of "automaticity." We are overwhelmed with information, mediated information constantly. It used to be that we'd talk about "the real world" versus "the mediated world." Today, it's just the world.

Ayrianna Jones:

You touched on a topic I wanted to talk about as far as reality and information overload. One thing I've noticed, especially in our generation, is people will use artificial intelligence like ChatGPT to avoid negative outcomes instead of dealing with reality and being human.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Okay, that's a great statement. I think that is... Again, there's research showing that people prefer to talk to algorithms—

Carolyn Hadlock:

When you say algorithms, do you mean chatbots?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah, algorithm-driven artificial intelligence, in essence. I think we are starting to see a lot of virtual or AI-generated pornography. Not a lot, but more of it. To my mind, it borders on the "uncanny valley" still.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Can you explain for our listeners what the uncanny valley is?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Sure. It's the idea that when AI and things that are created that are not "real"—whatever that word is going to mean in another five years—but mediated and generated things, robots and things like that, when they get closer and closer to being real-looking and you can't tell the difference, we become more and more uncomfortable. We become more and more untrusting of them. It becomes very unnerving to people when technology starts to mimic reality.

Carolyn Hadlock:

I would think it'd be the opposite.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah—well, here's the thing. I think it's a detection device, a protection device, that we don't want to be fooled. So the closer it gets when you still know that it's not real, the more uncomfortable we become because we're thinking, "How close are we to me actually falling for this?"

Ayrianna Jones:

I read that Gen Alpha and people who grow up in a fully digital world will rely more on artificial intelligence.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

I think it's a tool, and a very valuable and very powerful one. It's a reality enhancer. But you need to make sure that young people, as they're growing up, aren't solely relying on it. There's a great book written by a guy I studied under at NYU, Neil Postman, called Amusing Ourselves to Death. His argument was—and he was a McLuhanite, a media ecologist—he basically said you don't have to worry about 1984 and Big Brother is watching. Although maybe you do as well. But what he was saying was that you have to worry more about a Brave New World type of thing, where everybody is so entertained and everything is so perfect and you're always avoiding anything that's annoying or makes you feel uncomfortable.

Carolyn Hadlock:

It's utopia, not dystopia.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Right. Which actually is—you're living in a dystopia without realizing it. Just relying on technology is going to dull our senses. It does.

Jax Kordes:

There's a fine line between passion and addiction, and the only thing is that when people get to that line, they struggle to tell which side they're on. How do you see it?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

I think, in terms of information consumption and most process-style addictions—which are more the psychological addictions as opposed to chemical—there's actually a pretty good number of folks who argue that process addictions are a very gray line.

You know who's most likely to think they're addicted to pornography? Ultra-religious individuals.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Doesn't surprise me.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

But what's even more interesting is when you ask them how much they use, it's very little.

Carolyn Hadlock:

But is that true?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Okay, that's a fair question. But they'll say, "Well, how often are you using this stuff?" And they'll say, "Well, a couple of times a month or whatever." So the issue becomes: Are you comfortable with your use? Number one, are you dysfunctional in your own mind? Number two, are you dysfunctional socially? I think it is a different line for different people. There are certainly people who become very wrapped up in it.

It's a very trendy thing to call it addiction. So when you ask about the issue of addiction and kind of loss of control, I think it's a totally legitimate thing to be concerned about. But I do believe it's a very fuzzy moving target that depends on the individual. A lot of the research I've done looking into this issue shows—yeah, actually, it's not so much of an addiction issue. People who consume more pornography have higher libidos. Just like people with higher levels of sensation-seeking are more likely to skydive, more likely to scuba dive, more likely to bungee jump, more likely to watch sexually explicit material. So it's a much fuzzier question than just a fine line.

Jax Kordes:

And what do you think people who have these habits are actually seeking? Do you think it's more just the content itself, or do you think there's something deeper than that—maybe neurologically—that they're seeking?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

I mean, I think we like pleasure. And I think when you all reached out to me about coming in, that was one of the big things—the idea that pleasure is so easily accessible through media. Will we reach a point where it's easier to get your sexual satisfaction from media than from other people?

Carolyn Hadlock:

And I think that is the crux of the difference between pleasure and intimacy. Is it eroding intimacy?

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Right. And that's where AI potentially has the potential to play a role. When you start falling in love with or feeling like you have a relationship with these technologies, these technological entities, then we may start to see some concern.

I will mention one thing about AI-generated pornography. I don't think AI-generated pornography is as worrisome as some people make it out to be. I think what is potentially worrisome is the combination of that with extrasensory devices and technology—something called "teledildonics" or "haptic feedback sexual devices."

If you go on Live Jasmine or Chaturbate or whatever, they're using these devices—vibrators. Those vibrators on Chaturbate—you can pay tokens and push a button and increase the speed or decrease the speed of the vibrator. They have other ones that you can use with an individual. There was a Wii attachment years ago that I showed in class that you could use, and you could be on the other side of the world and control your sexual interaction with somebody.

Now here's where it gets a little tricky. We've got these—now they make very, very lifelike dolls. We're coming up with more technology that allows them to interact. You can make their sex organs way more stimulating than actual human sexual organs. I mean, I can't vibrate at 120 hertz no matter what I do, but a machine can. They can make stimulation that our bodies really weren't designed to respond to, but feels great. And it's the same thing as opioids—they're creating an environment that never existed.

Sex is a very powerful drive. And we don't have sex... When you're having sex, most of the time, especially when you're younger, you're not thinking "I'm making a baby." You're thinking, "This feels—"

Carolyn Hadlock:

Great.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

"I am enjoying this bonding situation. I'm enjoying this experience." And so is it going to just go away? Are we going to find something that's so much better than that that we just do away with the other part? And I think I can see a time when person-to-person sex is something of a fetish, some people's kink.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Oh gosh, that's crazy.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

And that's the thing—those that have a tendency to do things that lead them to procreate will flourish. Those that don't, will not.

There's a book—I can't remember who wrote it—called The Good Old Days Weren't as Good as They Seem or something like that. I think the issue becomes fear of change, what you grew up knowing. And this used to very much be the case because technology didn't move this fast. And this is where our brains are not made for this. We're so badly designed for the idea that technology doubles in speed every 18 months in terms of processing power and things like that.

We are in a period where our brains are confused and it makes us feel uneasy.

Jax Kordes:

I noted in your biography that some of your work has been cited by the Supreme Court, which shows that it's not just something personal, but also constitutional. What might that tell us about the stakes of what we're dealing with and how it's something on a much more elevated level?

Dr. Bryant Paul: That's a big question.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Yeah, that's a whole podcast right there.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah, it really is. But it's a great question. I mean, it really is. You guys have asked really interesting questions. Thank you.

I think what I tend to see with the judiciary is—and where I got involved with that—I've always been of the mind that I have this stupid saying: "No regulation without proof of causation." A lot of reactionary politics and reactionary laws are "I don't like the way things are headed." So they say, "Well, I'm going to be gone someday, but I want the world to be like it was when I was here." And so they put down a marker that says, "This law says you can't do this, even when I'm gone."

The courts, I think, are there to consider the constitutionality. And what that means is it's supposed to be a balancing test of what is best for society versus what allows individuals their personal liberty. The courts are supposed to consider that and come up with a ruling that serves all parties, I think, as best as it can.

There is a definite concern on the part of some individuals that letting us have at it with no guardrails is a big problem in certain areas. And sex is one of those areas, particularly in our society, because of how we're raised. A lot of younger people are—they become rather porn-averse actually. They like sexual content, just not so in-your-face. They'll just go watch it and then go do another thing. So they don't talk about it.

I used to do a lot of research specifically on pornography, and now it's like, there are so many other things—what are you really studying?

I think the fact that the courts are getting involved in all this stuff shows that our craving to be comfortable, our desire to feel safe, the world's going to be okay even when we're not here anymore—that's something that really matters to people. And what it shows you is that what we want, at some level, is what we think is best for ourselves.

Carolyn Hadlock:

That's the ultimate craving.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

The ultimate craving is Maslow's hierarchy of needs—to make sure those things are satisfied. And the fact that we deal with these kinds of what I would say are fringe issues—"Should we allow people to be on TikTok? Should kids be on TikTok?"—think about how great we're doing. I'm sorry to be overly optimistic, but—

Carolyn Hadlock:

No, I actually am pleasantly surprised by it. It's interesting.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

But think about how great we're doing if we're not worried about food and shelter to the degree that we are... Although some people are, obviously. But the fact that we can talk about "Should young people have access to a social media environment that is unregulated?" That, to me, says, "Wow, we've got the basics pretty well covered."

Carolyn Hadlock:

That's interesting.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

I think we should take some solace in that when we're worrying about what a mess the world is. There are places in the world where they don't get to do that. They just wonder, even in this country, "Where's my next meal coming from?" The fact that, as a society in the United States, we're able to have those conversations—I take some positivity out of that. It seems to me that despite all the doom and gloom... And that's one of the things I worry about the most with our field, is that everybody's like, "Oh, media, it's all terrible."

Is it really? We're having this conversation right now. I think this is great.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Yeah. I'm curious—Jax and Ayrianna, are you surprised by this conversation? I'm very, very surprised.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Really?

Ayrianna Jones:

Well, more so because I don't see it as optimistic. I guess it comes down to what you said—individual perspectives.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

The way I see it just might be different.

Ayrianna Jones:

The way I see it just might be different.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Completely. And I would just put to you that I think a lot of that is the media doom and gloom. We are presented with so much negativity. We focus so much on "Oh, this is terrible, and that's terrible."

Carolyn Hadlock:

And our brains love that.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

That is something I think you could potentially say we're addicted to—

Carolyn Hadlock:

Negativity.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

Yeah, negativity. Because we have to, right? You've got to avoid that burning house. So you've got to remember—but the burning house isn't actually there.

Ayrianna Jones:

I think this is a great conversation. I definitely would like to pick your brain more afterwards. I definitely have perspectives that I think could probably be different from yours, but it's interesting to talk about.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

And I welcome that. I think that's another really important point: Don't run away from perspectives that differ from your own. You don't have to like them, but you need to hear them. The only way you're going to understand or potentially help other people—if you really think you're right—then it's probably in your interest to help them understand where you're coming from.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

Dr. Bryant Paul:

This was really great. Thank you so much.

This episode was created and produced at the IU Media School as part of the Beautiful Thinkers Podcast, IU Edition. To follow along this season, check out The Beautiful Thinkers Project on Instagram and LinkedIn. Special thanks to our students who researched and reported this episode: Jax Kordes, Ayrianna Jones. This episode was produced by Maiza Munn.