On the third episode of Season VIII: Polarity - IU Edition, Carolyn Hadlock and IU Students Asher, Lauren, and Kate welcome Founding Dean of the Hamilton Lugar School of International and Global Studies, Lee Feinstein, to discuss his journey to becoming the school's founding dean and his efforts to enhance global engagement and international studies at Indiana University and around the world.

Lauren Gee, Asher First, Kate Carls

" I don't mean to be pollyannaish about this, but I think whatever people's political perspectives are, I think most people overwhelmingly want to find a way to move ahead and focus on the problems that we all face. And to do that as best as we can together rather than splitting each other apart." -Lee Feinstein

Carolyn Hadlock:

Today we are talking to Lee Feinstein, the former policy planner and ambassador, founding dean of Hamilton Lugar School, and president of McLarty Associates in Washington, DC. Welcome to the show, Lee.

LeeFeinstein:

Great to be here.

Lauren Gee:

We just wanted to begin by talking about our season theme, which is polarity. We found this to be really interesting because it tends to have a negative connotation in society, but we’re wanting to focus more on how polarity can be a positive thing, whether that be within relationships with your friends and family, in society, or even just your own inner conflicts. We were wondering if you could touch on at all how polarity can be a positive thing and maybe introduce new ideas when you are talking with people who have opposing views.

Lee Feinstein:

What a great way to talk about an important issue. And I noticed that you used the word polarity rather than polarization, and those are definitely different things. I think what I see in your choice of this is it's important to listen hard and sympathetically to what other people are saying, what their perspectives are, what their inner lives might be, what they might be going through, where they're coming from. also in my role as the founding dean of the Hamilton Lugar School, literally where they're from as a way to understand more deeply what their points of view are. Doesn't necessarily mean that you agree, but the point is to really work hard at listening and understanding different points of view as a way to understand things more deeply and from a position of humility, because from humility comes inability really to, I would say, to make change, to make really lasting and sustaining change.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Yeah, I think sometimes we perceive listening as a form of agreement.

Asher First:

And that's really, that's where we came up with the theme for the season because every day we all see how divided people can be on the simplest of topics, and we really want to advocate for people to just listen to each other.

Lee Feinstein:

Well, look, this is a great thing about being at IU and a great thing about being in Indiana because first of all. I mean, we think about states as red and blue, and I guess if you had to assign a color to Indiana, you would assign red and people talk about the blue dot of Bloomington, but the truth is, there was a wide range of views on campus and you don't have to travel too far from campus to get also very different kinds of perspectives.

Carolyn Hadlock:

One of the things we noted about your reputation, Lee, is admirable, and just curious how you have continued to foster this reputation as a bipartisan or nonpartisan in a career where you have tackled extremely tough topics. Was there anything in your upbringing or what has shaped you and kept you on that track to maintain that reputation?

Lee Feinstein:

That's really interesting and thank you. I would say just thinking about family influences. Neither one of my parents was politically engaged in any significant way, but both of my parents had, I would say a high integrity meter. And if they felt that someone was being disrespected or not treated fairly, it got them, it got them angry and they responded in, I think a very positive way to that. We kind of grew up in a very basic middle-class family. Everybody lived on, everybody lived in the same house. They were all quarter-acre lots. And so people didn't, there wasn't FOMO in the neighborhood as far as I could tell, because everybody's houses were the same and people came, almost everybody was, the family was from somewhere else within a generation or two. I would say they certainly didn't have worldly experiences in the sense that they didn't think globally or about global problems in the way that all of us in this virtual room do, but they kind of had a certain basic respect for treating one another. When I got to graduate school, I got interested in political philosophy sort of late in my college career. And then I pursued it a little bit further in graduate school. And I had a professor who had a big influence on me. His name is Marshall Berman. He was really interested always in looking for people and voices that perceived what was going on in slightly different ways as a way to understand it or to look at the polarities. He had us read a book by Buchner, it was also made into a movie about Danton versus Robespierre. they of course became mortal enemies literally. But they both had a lot to contribute in terms of their political thinking. One took a very despotic direction and one took, I would say a very principled but politically disengaged direction at the end as well. But the importance of this perspective was to read and understand both of their perspectives about what makes a change. And they had very, very different perspectives and their clash has had historic significance since the French Revolution.

Kate Carls:

We know you have a lot of experiences and we wanted to know in your career, how do you help people find common ground without compromising their opinions or disrespecting their beliefs?

Lee Feinstein:

I really like what you said because sometimes people think that hard listening or trying to develop common ground is sort of suspending the right to have a strong opinion about something. And I think it's important to see that that's not the case. Things may not turn out the way you want, and often they don't turn out the way you want. But trying to work with people to move ahead is about really trying to build unity, which is a sustainable way, the most sustainable and lasting way if you can do it to make a change. So I've had a lot of experience doing that in different ways. And over time I was at the Council on Foreign Relations for five years and I was on, and I helped to run a program called the Task Force Program. And what they would do is they would bring people from different political ideological perspectives, different academic and professional perspectives to talk about ideas, different, I should say different global challenges and how to address them from energy to policy towards Iran or Russia. And the goal of this project was to come up with findings and recommendations that were not plum, but actually kind of reached some strong conclusions that the group could agree on. Sometimes it succeeded better than others, but that was a really important experience that I had. And then I had a bigger version of that where the US Institute of Peace, which was a think tank that's funded by the US Congress, but it's an independent think tank, and the Congress had authorized them to do a report on the United Nations and US role in the United Nations, which was then and remains now a very contentious issue. I mean, the security council in particular is outdated, unrepresented, deadlocked, and a disarray and really in need of renovation just for starters. But the co-chairs of this committee were a former Senate majority leader who played a very strong role in Middle East peace, whose name is George Mitchell, who's a Democrat, and Newt Gingrich, who people probably do know, who's a former speaker of the house and is I would say, well, he's a Republican and I'd say he's on the right very far right of the Republican Party. And they were the co-chairs of this task force. I ended up starting, I was asked to help George Mitchell. I staffed him to work on this report. I was also an expert on some of the issues related to democracy, human rights, and peacekeeping. But I was asked to advise George Mitchell. Then the staff director of the project dropped out for one reason or another, and then they asked me if I would also do the same thing for Newt Gingrich. And politically, I don't have a lot of common ground with Newt Gingrich, but it was a really interesting experience and it was a really important report that was balanced between left and that came up with some really good recommendations at the end of the day. And there were some surprises. In some cases, Gingrich wrote some of the strongest advocacy for points that Mitchell and I and others supported among the recommendations.

Carolyn Hadlock:

That must've been surprising.

Lee Feinstein:

It was surprising and I learned a lot.

Asher First:

Alright, you have a research project titled Allied Cooperation in Atrocity Situations. In the research project, you stated that you wanted to evaluate steps that like-minded states can take to deepen their cooperation to prevent and stop mass killings. In what ways do you believe these states need to be like-minded and do all states have the ability to find this common ground to prevent these mass killings and atrocities?

Lee Feinstein:

Right. It was a paper from several years ago. the issue was more broadly how to deal with conflict situations and to change the global mindset around these issues, which is in the case that I was personally involved in the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya From Myanmar, I visited twice Burma, Preco, and also Naypyidaw, which is the sort of the Star Trek-like capital of Burma to try to understand better and what was the government policy to drive out this Muslim minority and to work with civil society in an effort to change the policy and also to take steps to end the government policy. There was a rising group of civil society that was working on ways to deal with social media and its very, very negative impact in that conflict. Social media was used to stoke the conflict to stoke hatred and vilification of this minority consistent with a longstanding policy of the government to deny them of their identity and personhood in the context of Myanmar, and this was sort of in the earlier days of Facebook, but at that time in Myanmar, people's access to the web on their phones was through Facebook. And the government used Facebook to stoke and intensify efforts, which was partly successful in expunging Rohingya from the country. And that effort about social media's impact is continuing, particularly in the context of these kinds of situations.

Kate Carls:

You touched on how interesting it is that the Hamilton Lugar School is that Indiana and Bloomington are kind of the blue in a predominantly red state, and why you thought IU would be a good place for a global and international studies school. So we wanted to know what the visions were for the school and what the goals were coming in.

Lee Feinstein:

Well, that's great. Well, I've been really lucky in my career. I've had a lot of great experiences, but at the top of the list for sure, and not just because I'm talking to all of you in Bloomington, was being dean of HLS, and the initial vision was not mine, it was the universities and its leadership, and it was to bring IU history and strength in area studies, the study of the languages and cultures of different parts of the world together with a thematic approach to understanding international politics through different lenses. And that historically in between the wars when this field was created, was kind of the initial vision to kind of combine knowledge of place with a functional understanding of things. And that's been lost. And so the idea was to put these two things together, and I think it's really important. I'm personally very interested in political theory, but knowledge of place is extremely important. And the combination of some theoretical understanding or cross-cutting perspective, whether you're focused on non-proliferation or democracy issues or global trade with a deep understanding of a place or of the world is I think kind of the sweet spot that the school really focuses on.

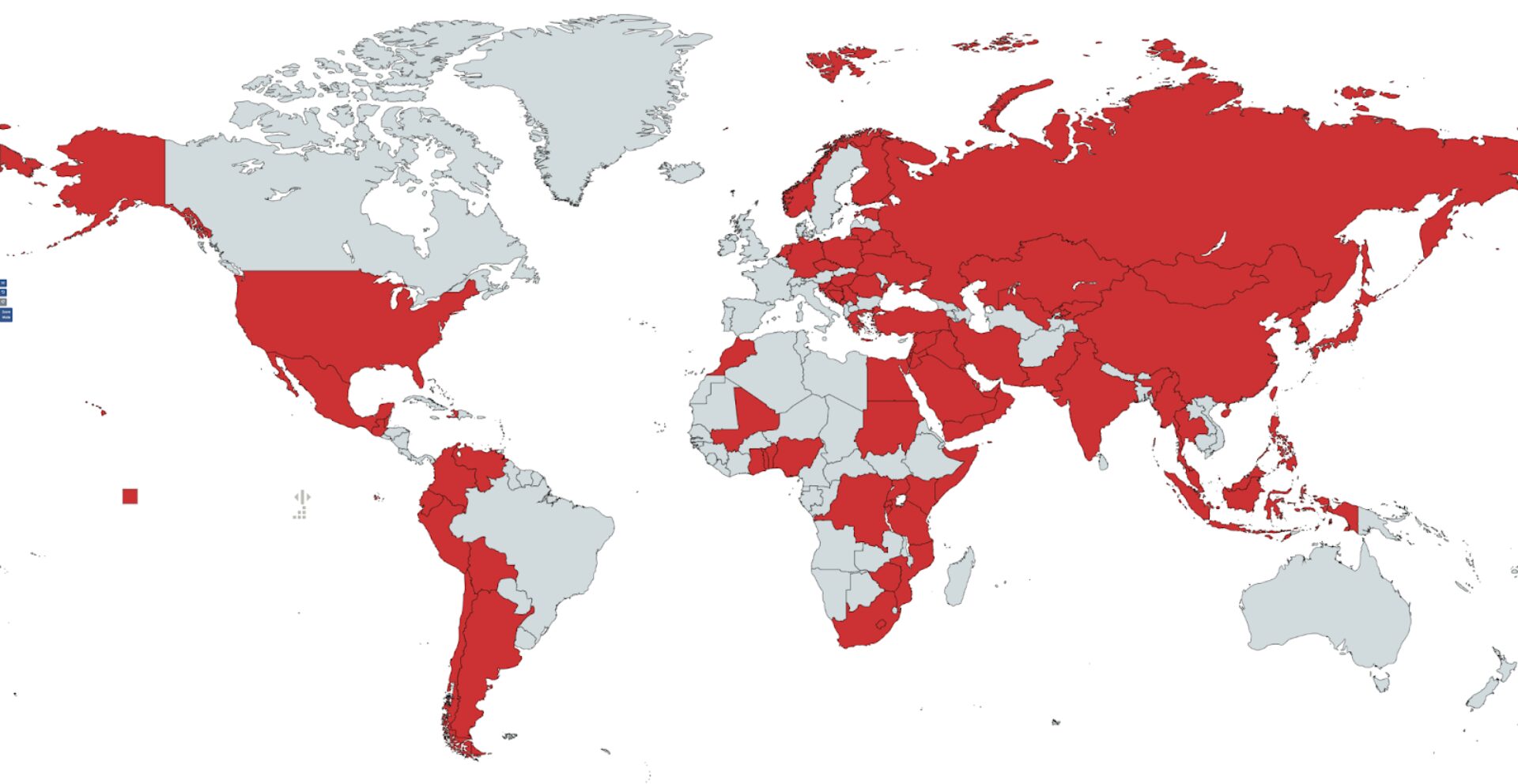

Indiana University’s Hamilton Lugar School teaches 80 languages, making it the leading institution in the country for language education. This map represents the regions and countries where the languages taught at IU are primarily spoken in the world.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Do you think being in Indiana has helped facilitate that sort of openness and lack of bias to really deep dive into that knowledge of places around the world?

Lee Feinstein:

Fundamentally and looking over time? I would say yes, in many parts of the Midwest, including in Indiana, there's this kind of all small piece, progressive global tradition Like looking outward. And the school, we named the school after Dick Lugar and Lee Hamilton, and those are two guys who really reflect that tradition. One was a Republican, one was a Democrat. They both received presidential medals of freedom from President Obama. And they were both people who had a very big global perspective and actually real global responsibilities. they both believed in the importance of principle over party and the idea of principled US global engagement as being really important, principled being the operative word there

Lauren Gee:

We've heard a lot about your role as a scholar and we're just wondering if you could touch a little bit on your role as a practitioner, so we understand going to Poland, how you are kind of opening up and bridging this gap between the United States and Poland and how you're representing the United States and Poland and vice versa? So we were wondering if you could tell us a little bit more about why you chose Poland?

Lee Feinstein:

Well, the way these things work, I remember I was in a Starbucks outside the transition office in the early days of Obama, right after the election. The way these things work is I had a list of places I wanted to work and I discussed them in the Starbucks with the person who became his national security advisor. And Poland was one of the places on the list. And of course, they're the ones who chose not me, but I felt it was one of our top choices for a couple of reasons. First, my wife and I both had studied about central and eastern Europe, and so it was interesting to us. And my junior semester abroad was in what was in the Soviet Union, and my wife had worked as a reporter in Ukraine and Russia, and other parts of the former Soviet Union. So that was kind of literally a place where we met and our interests met. Both of my grandparents were born in what was then Poland, and then well, what has been Poland historically and was once part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire, part of the Russian parallel settlement, and now both of those areas are in Ukraine. So it had more than a little personal resonance for me. And then from a policy perspective, it was an ambassadorship where the ambassador can be pretty deeply involved in the policy and where there's policy work to do. And so I really felt like it was a sweet spot, and so that was what I would hoped for, and there was a lot of policy work to do and it picked up on some of the experiences, policy experience I had had and policy work I had done, which was really gratifying and also gave me an opportunity to just grow into areas that I hadn't really worked on before.

Asher First:

You attended the General Assembly Week, would you say that there's a sort of separation between how the media covers the event versus the actual event itself? And do you think that the understanding of this event could affect polarization among different nations?

Lee Feinstein:

That's a great question. It was actually my first time going to general assembly week, UNGA week, So it was exhausting. There are really frustrating aspects of this as I was sort of describing the UN Security Council as deadlocked and dysfunctional and in disarray, in need of renovation. But what happens around UNGA Week is this incredible set of convenings that bring all different kinds of people from everywhere to New York for a few days. And I found that unexpectedly to be less about swanning and more about trying to figure things out. And so at a time of lots of justifiable pessimism, I found it kind of invigorating and even a little hopeful. It was surprisingly, I think, important and it's just important for people. I mean, it's very consistent with the theme today. There's lots of polarity, but people being together to meet, to talk about these things is just in itself. It's not enough, but it's really valuable. I also brought some of my worlds together because I had a chance to reside at a panel with my former counterpart in Poland who's now in the role. He was then the foreign minister of Poland, and it was at the Council on Foreign Relations. So I had both my work in Poland and my CFR work coming together and that was really gratifying.

The UN General Assembly Week took place in the United Nations Headquarters in New York City from September 10 through September 28, 2024. This assembly was the 79th annual gathering of world leaders and citizens from around the world with the main purpose of progressing world peace through discussions concerning international issues.

Asher First:

Yeah, it surely sounds like an incredible event to be part of.

Lauren Gee:

We would also love to hear about your biggest accomplishment, something that you're really proud of, maybe something that wasn't very advertised at the time.

Carolyn Hadlock:

I think the idea is a quiet accomplishment, something that wasn't really merchandise but you're quite proud of.

Lee Feinstein:

Well, that's awfully nice and a little embarrassing to answer. So let me see if this begins to answer your question. I learned a tremendous amount moving to the Midwest. I grew up in the New York City suburbs and I didn't have in my mind's eye even the idea that I might spend a big chunk of my life in the Midwest. And it was a huge learning experience and I feel like I grew tremendously by being at IU and in Indiana. I'd say this is a Personal improvement, which is that I think I would like to think I got less judgy.

Lauren Gee:

You had talked about strengthening solidarity in the US during that panel, and we just wanted to know where you think the US is lacking that solidarity and maybe how we can go about fixing it.

Lee Feinstein:

Great question and a really important one. There's a lot of focus on the US approach to the rest of the world on what the policies should be what ones will be more, most effective, and how you develop those. And we've been talking a lot about that in the last hour, but none of that is possible in a country that is divided if there isn't a kind of very basic agreement on the idea that one way, in one manner or another, the United States should be engaged globally. The most brilliant foreign policy mines can't effectively move ahead. Everybody talks about, I mean the phrase would be foreign policy begins at home. It's just really true. When the United States is divided, it can't be effective globally in advancing its goals. This is also true in other countries when they're preoccupied at home, it has an impact on how they choose to interact with their neighbors or globally. So it's just a very important point that it's not to say that everybody has to agree on a particular course of action. It's basically that there needs to be basic agreement, or at least acquiescence in the idea that we can't do it alone. That turning inward helps no one in getting the balance right. That's kind of a big part of what this election is about. How much and how should the United States be committed to one thing or another overseas? And that is really important and valid, but the idea that you can just kind of turn inward, unless there's kind of an effort to build consensus around the idea that that's not realistic, it becomes really difficult to do much of anything globally.

Kate Carls:

Now that we're one week away from the election, how do you think it is being viewed from a local as well as a global stage? And how do you think we can process the election votes afterward?

Lee Feinstein:

I think a lot of the stuff that's happening in the United States has become normalized at home and normalized globally. So people have their favorites. People are concerned about one result or another. I think countries are like that too, at least their leadership is, and the public. But in a way, I think what is developing is this sort of idea that we have to deal with the United States as it is, and whoever wins the election, these kinds of problems that exist, they're going to persist. And so we have to think about what our global positioning should be. and division is not something that others, US friends, allies, partners, and others want to see. And certainly us adversaries, there's a sort of degree of schadenfreude about that glee and sometimes and social media and other things. But there's just kind of an expectation that this is the way it's going to be for the foreseeable future and whatever the result is, it's not going to fix the problem.

Kate Carls:

Aside from the outcome of the election possibly impacting our foreign relations, how do you think we can maintain peace as a country?

Lee Feinstein:

How can we maintain the peace of the country? I mean, look, I think my answer to that is that this country is far from perfect and the democratization of the country has come over hundreds of years and in phases, but there's a lot of strength and integrity in the country. And I think that describes most people in the country. And so at the end of the day, I have confidence that in efforts to sort of tear us apart, that I think at the end of the day, that's not what people want. And that as a country, well, I don't mean to be pollyannaish about this, but I think whatever people's political perspectives are, I think most people overwhelmingly want to find a way to move ahead and focus on the problems that we all face. And to do that as best as we can together rather than splitting each other apart.

The 2024 presidential election between Kamala Harris (D) and Donald Trump (R) caused great controversy among Americans all over the country. While politics is often a very dividing topic in the United States, Feinstein believes that, as a nation, Americans must have a common goal of coming together to fix the issues at hand.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Something you just said a minute ago was a light bulb moment for me when you said that regardless of who wins, we still have issues. And I think that we're sort of being forced into this black or white, good or bad left sort of decision when in reality it's far bigger than that, which I think is a really interesting way to think about it. Any advice for the Thanksgiving holiday coming up, regardless of how interesting this is, we intentionally wanted to talk to you before the election, but fully knowing that your episode will probably be the week after the election.

Lee Feinstein:

My advice would be to breathe more and drink less

Asher First:

Insightful stuff.

Carolyn Hadlock:

Thank you so much, Lee, it’s been a pleasure

Lee Feinstein:

Really nice to meet everybody.

Carolyn Hadlock:

All right, have a great day.

Lee Feinstein:

Okay, bye-Bye

Carolyn Hadlock:

Thank you so much for listening to this episode. This episode was created and produced at the IU Media School as part of the Beautiful Thinkers Podcast, IU edition. To follow along this season, check out The Beautiful Thinkers Project on Instagram and LinkedIn. Special thanks to Bella Grimaldi for our music and the students who researched and recorded this episode. Asher first, Lauren Gee and Kate Carls.