Isabelle Wu

A hot topic today in the US, especially in this current time, is what is free speech, what should be allowed, what is unfettered, and who is the arbiter, who is the judge?

Carolyn:

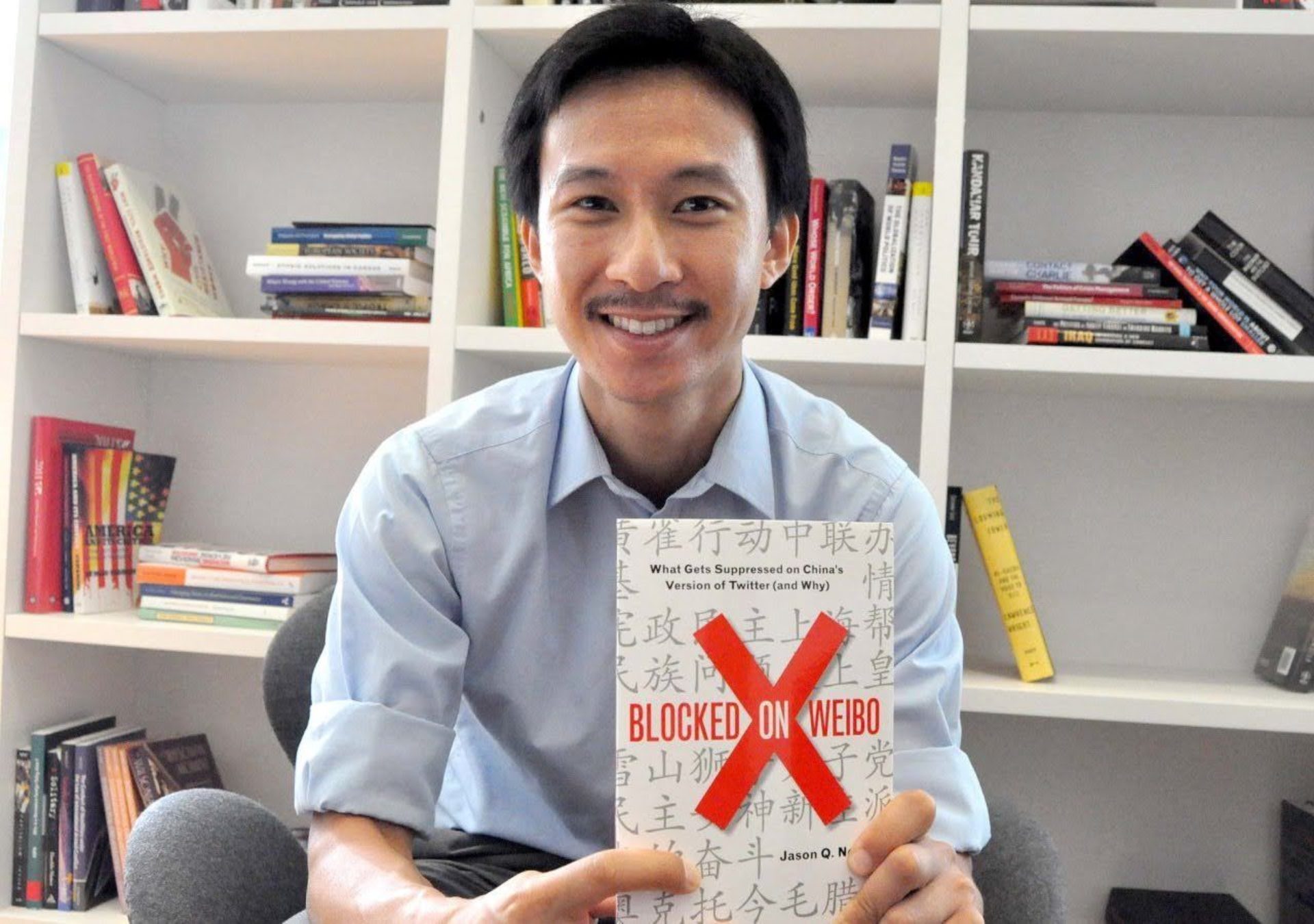

Today we are talking to Jason Q. Ng. He is the senior data science manager at Duolingo, as well as the author of Blocked on Weibo, which I believe just had its 10th anniversary. Welcome to the show Jason.

Jason:

Oh, thank you for having me. I'm really excited to sort of rehash some old memories and thoughts about my time writing that book, but also happy to talk about more current events and our work. So go for it.

Carolyn:

Great! I thought it might be nice to have Isabelle talk about why she brought you to the roster.

Isabelle:

Yes. So my parents are actually from China and my mom was a reporter. I actually called her an hour ago to talk with her about her experience. She talked about how there were so many times where she would have an article written and ready to be published, but then the government would intervene and say “We don't know if we want you to publish this because there's some information that might not be great for the public to know about”. And they would scrap it. It was very interesting to hear about her experience growing up with that level of censorship in China. Whereas like me, in this day and age, I literally have access to media at my fingertips whenever I want.

Jason:

That's fascinating to hear about your personal connection to your Mom and her experiences with, I think what some might call censorship and others might say is appropriate, is regulation of media, which is a very hot topic today. And in the US, especially now, we are asking what is free speech, what should be allowed, what is unfettered, what is what does that all mean and how much how much should we want to have someone to say, “Hey, actually that's not good for the health of your society”, but who is the arbiter? Who is the judge? I think those are fascinating questions and it's really cool to hear that you have that personal connection.

Carolyn:

All right. We're going to come back to the current times because it does sound like there's a lot happening right now. And your point that you raise, Jason, is a good one. Who is the arbiter of free speech and how does that operate? But maybe for purposes of level setting can you talk about “Blocked on Weibo” and how you did it? Maybe just take a minute and just introduce us to the book for those who aren't aware.

Blocked On Weibo was published in 2013.

Jason:

Yeah, and so this was a book like you said, which was published ten years ago in a very different context. It was a world where we had a lot of sort of optimism for what the Internet could provide. And hopefully there is still some element of optimism about the Internet being a force for good still in the core of our hearts. But at the time in the context of a world where the Arab Spring was just around the corner, where people were still couch surfing, people were making the most of their connections online and being able to find and relate to each other. It was a really wonderful space. It was also a world where the Internet was slow and it was dawning on folks that there were opportunities to be had and figure out ways to control it. Thinking through that, it's not just a, you know, a hobbyist space where fun things can happen, but also it's a way to put forth propaganda, a way to control thoughts, a way to manipulate public opinion. These are all things that were coming to bear at that time. I was working on this book and it was sort of happenstance that I sort of stumbled on this topic. I had started a graduate program at the University of Pittsburgh, and I happened to have as my advisor, a political scientist. And, you know, I had originally wanted to study book publishing.

But we started to think about the opportunities for different kinds of exploration around media. And he had an interesting question around, “Hey, isn't it interesting that typically politicians love having their names in the headlines. They love having their name in the news. It's kind of interesting how in China, you know, certain politicians, they're actually not as easy to look up information about. They actually don't want their names in headlines. They don't want their name in the news. You know, why is that? How is this happening? And this led me to sort of down a little bit of a rabbit hole and I found there is this kind of perverse incentive to not or disincentive being attached to any news that could be sensitive. And if you as a politician aren't really sure what is sensitive, maybe it's better to just not be connected to certain affairs or certain news items. And so to play it safe and not be findable was the better way to go.

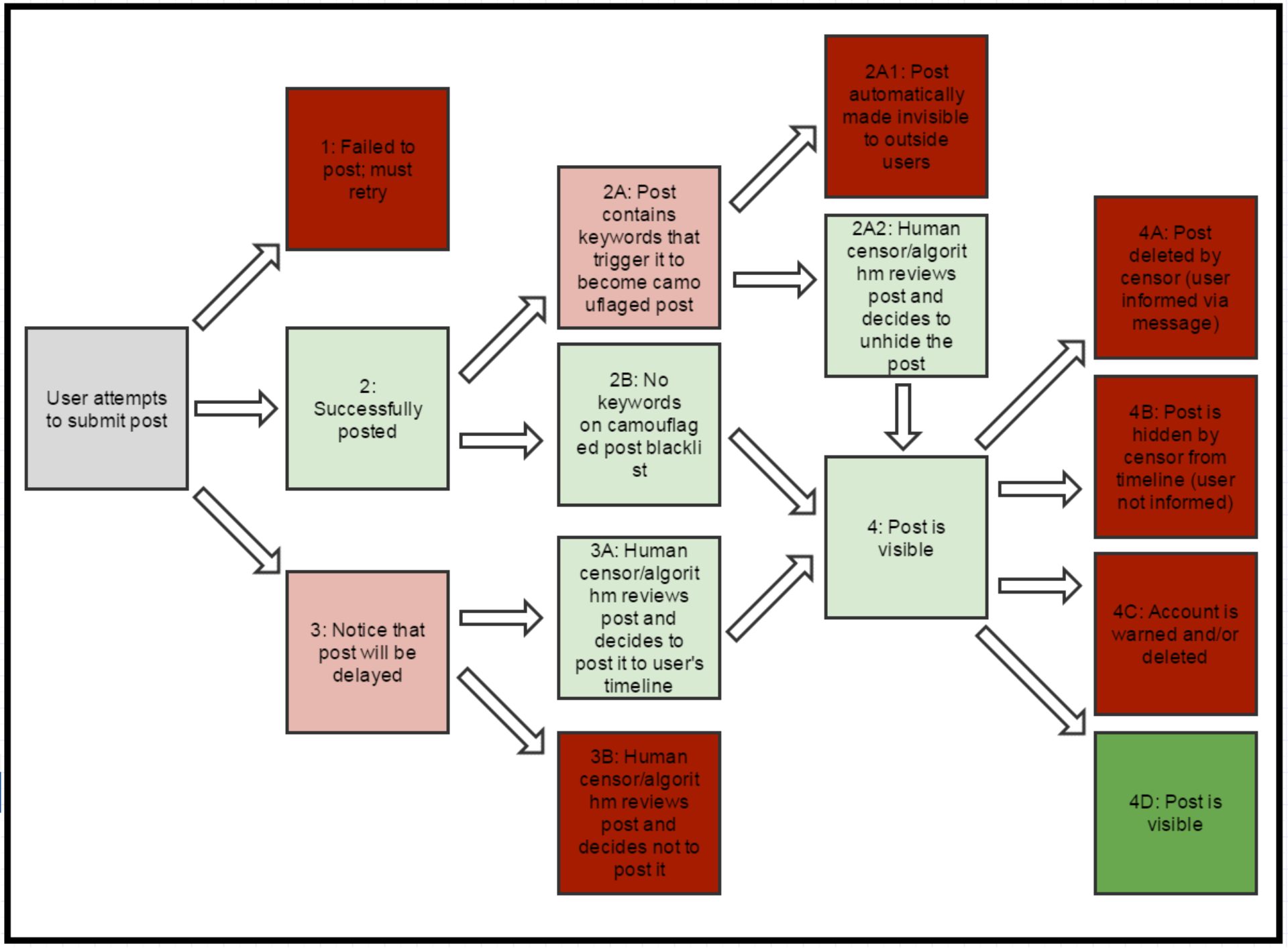

Flow Chart of search terms.

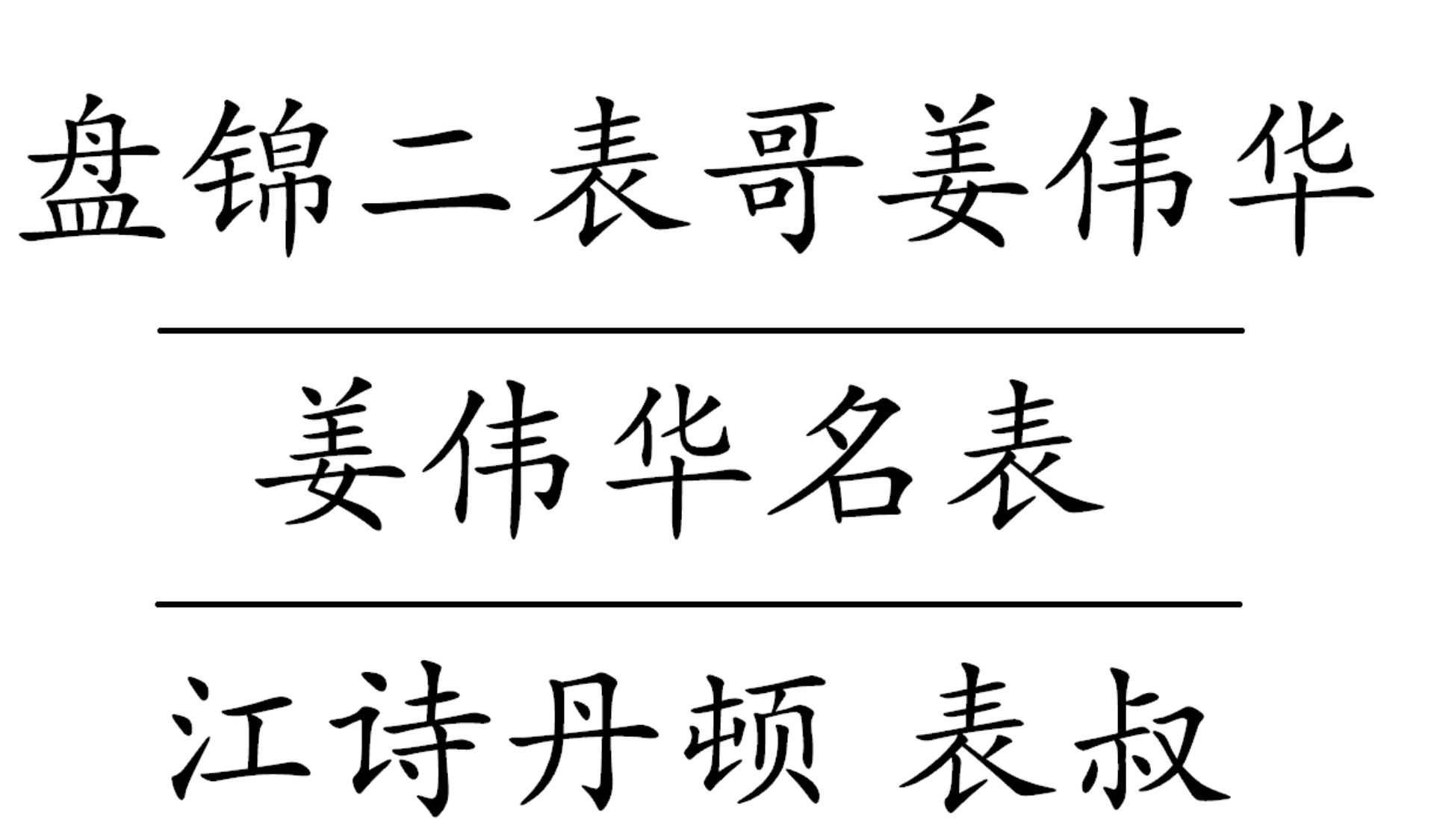

These three terms in Chinese refer to government officials who were caught in photographs wearing expensive wrist watches.

Carolyn:

Are they literally calling folks to tell them, hey, don't put me in the news? Or is this something that has happened at the company or governmental level? And if so, how is that happening? And wasn’t that the genesis where you identified search terms on social media websites like Weibo.

Jason:

So if folks aren't familiar, Weibo is kind of like Twitter in China and when you search for certain what you might consider sensitive terms, like certain politicians names or illicit drugs on Weibo when you enter them, it spits back a message that literally says according to rules and regulations and laws, we we we can't show you search results for this. So that's really fascinating. Think about how that happened and what else is there? What is the full universe of things that they're blocking? And so that was interesting to me as someone who's very curious. I wasn't a computer scientist, but I could tinker with computer programming. And so what I did was I wrote up a computer script that took in what I thought was a good corpus of words which was all Chinese, Wikipedia and did a script and basically tested them out on a website to see which ones were blocked. And, you know, there were ones that were pretty obvious.

So like I said, censored politicians names and certain sites where there were protests. And some might be terms you’re familiar with, like “tank man” is a reference to the man who heroically stood in front of a tank in the Yemen square in 1989. So these are obviously ones, but then there are others that are much less obvious and it sort of gets at the edges of what is acceptable speech? And so it was a fun opportunity for me to write up and sort of present those, you know, array of terms, but also sort of an understanding of where I saw my best guess at why some of these terms might be considered sensitive in China and offer a lens into that world.

Isabelle:

Was there anything that really surprised you when you went through that process?

Jason:

As someone who did not spend my entire life in China—I visited China and taught English there as a sort of fun thing and I went back to see my home village— but I never really lived there and so I have a very different experience than someone who has grown up with Internet censorship.. And so and as someone who when I started my graduate program this was all relatively new to me. It was very surprising how borderline topics that are technically not illegal are still still sensitive online, at least according to what was censored on this particular website. And what was particularly interesting to me was some days certain words would be censored and other days they wouldn’t be and I’d go, Well, what happened? How did this happen? Did someone make some grand change and decision or was it just some engineer? So, perhaps the most surprising thing to me was the variability and how in many ways decisions were individuals implementing these policies. That's just it's kind of hard to wrap your mind around.

Carolyn:

Yeah, that's a lot. One of the things Isabelle and I were talking about before this interview is you have one of the most interesting paths of anybody I've seen. You went to Brown and studied English, and then you did your graduate work. You worked at the Citizen Lab and did data visualization on incarceration. You wrote this book, you worked at Spotify, you work at Duolingo. Connect the dots for us. What is the commonality here?

Jason:

That's a great question. I think I ask myself that every so often. I think the through line here is of being open and curious to the opportunities. I would like to think that a lot of the work that I've done is in the spirit of wanting to understand the world we live in better. But that's kind of grandiose and obviously, you know, we're all just playing a small part in trying to add to our understanding of the world. But yeah, I think that's what drives me. So going all the way back to my time working as a book editor, to my current work as a data scientist, and helping others to figure out how people are learning languages and how best to make their experience positive on a learning app. I think that's the through line. But I don't honestly have a clear answer for how it's all connected.

Carolyn:

And when you were at Spotify, what was your role or what did you focus on there?

Jason:

Yeah, I was a data scientist as well as well, and it was really fun in that I was actually a music deejay out of college radio station at Brown, and so it was in many ways a dream job to be able to think about how I would use data to empower the people I looked up to the most at the time, which were musicians and folks who are trying to just share their love for for, for audio and be able to communicate that via the audio and, and music. I worked on a team that built out tools to help artists put their music directly on Spotify and figure out ways in which we could help them connect with other musicians to build. They built their music collaboratively online. And so, yeah, it was a lot of fun. And I got a huge kick out of, you know, being able to have at my fingertips and so much interesting data around, around musicians that I just grew up loving and listening to all the time

.

Carolyn:

I feel like Spotify uses data brilliantly. Even now I'm so excited for “Wrapped”.

Jason:

Yeah it's something that taps into how we are, how we're all kind of a little bit narcissistic in that we want to know someone likes to pay attention to us and tell us like they know a little bit about us. And so, yeah, there’s certainly some element of that. And I know that other companies have started doing similar types of things.

Carolyn:

That's interesting. As you talk about helping artists get their music published it seems like another throughline maybe for your work is how you help democratize things and level set things and help people access platforms and technology.

Jason:

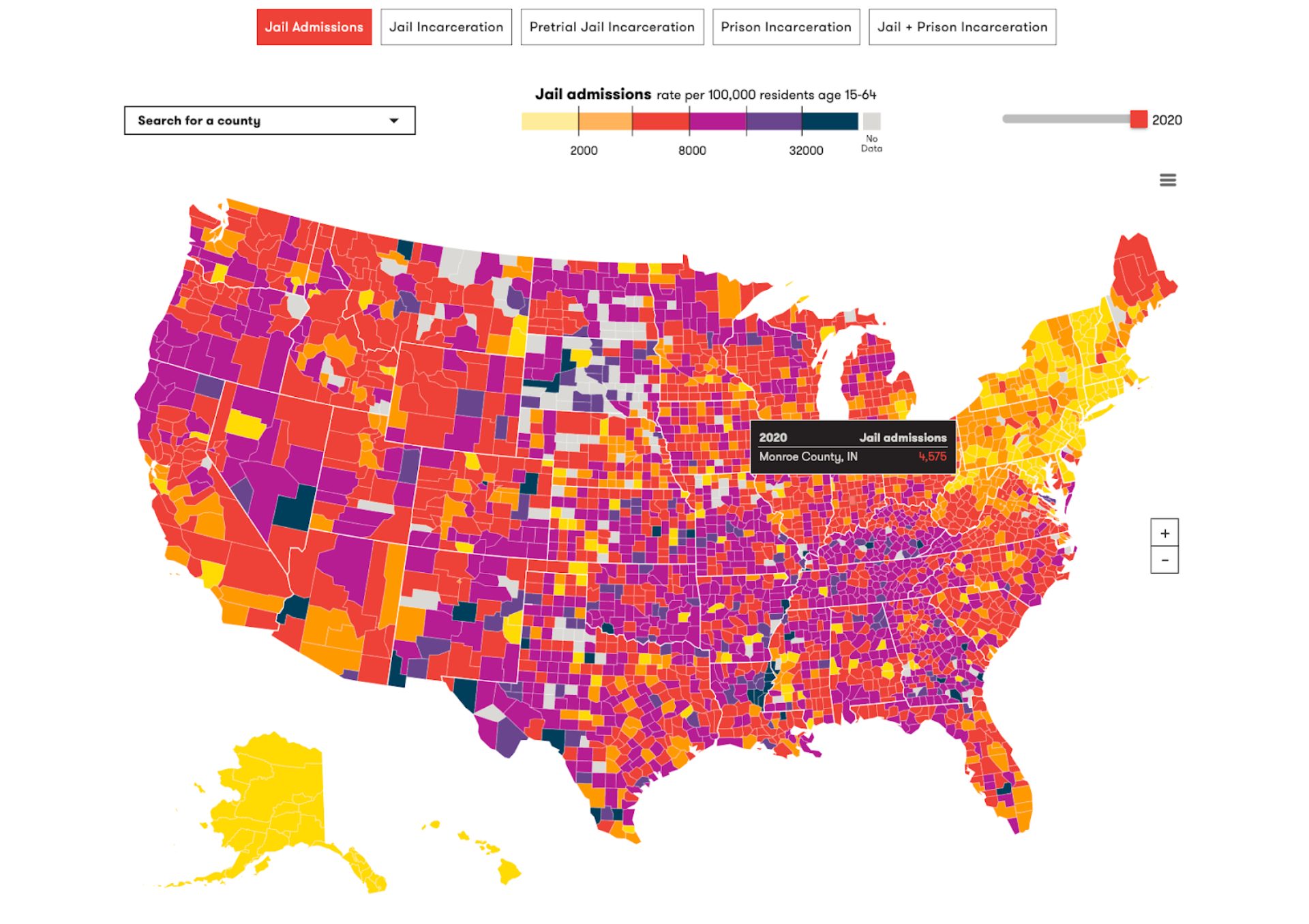

Wow. That's a great segway. I hadn't really actually put that in my head. I was like, Oh yeah, I do like teaching, I like sharing things out. And yeah, maybe that's some element of what attracts me to this kind of work. But yeah I think Duolingo is a little less of that. In my previous role at the Vera Institute I worked with an incredibly talented team. I was not the leader of it. I was just very lucky to be part of it, collecting data, visualizing what was happening with, with what we saw in incarceration trends across the US, and having that data available to researchers but also policy advocates and legislators. In other words, for everyone to be able to marshal that data, to prove that more often than not, we are very much a culture of over incarceration. In my current role I work on a team that is focused internally on trying to improve our product. And we've noticed that one of the most impactful ways to convince folks that your data is speaking truth and being able to have impact is being able to visualize it properly.

Incarceration Map by Geography

Courtesy of the Vera Lab

Isabelle:

I'm not sure if you're familiar with our season concept of saturation, but the whole concept is that media is so accessible these days, it’s at our fingertips. The idea of saturation comes from the overload of information to our brains. Do you think that this issue of overconsumption is seen in Chinese media or is it just because we barely have any censorship here in the US?

Jason

So the content is really interesting to think about. Thank you for bringing that question. In some ways, when you think about censorship, you think about censorship as taking away content from people who want to be able to view things. But another way of thinking about censorship is you're basically just distorting the truth. And so you could think of a broader definition of censorship in some ways including propaganda, and it includes intensely over saturating the message that you're trying to distort. And so, yeah, I think it's really interesting. And the authority figures around the world, not just in China are learning that the sort of cut and dry, more canonical definition of censorship where something is taken off or blocked may not be effective because someone has already seen it clearly and someone has produced it. And so, that message may go viral. It may be your intentionally taking it away produces this kind of what would folks call the Streisand effect of like shining a light on something that may have been innocuously ignored before, but now, like, you've taken it away and now people are like, wait a second, something was going on here, something is up. It sort of brings fire to folks who are already passionate about an issue. You're intentionally trying to sabotage or trying to shut it down. And so with that learning, a lot of governments are leaning into strategies like propaganda, which is pushing out your message as opposed to taking down another message. Alternatively, when there is a message that you don't like, instead of presenting an alternative point of view, you just drown it out. And maybe that gets to your question of saturation.As individuals, we are already inundated with so much information on a regular basis through social media, through news that we try and seek, through notification pop ups that are happening on our phone every few seconds.

Carolyn:

Yeah, I hadn’t thought of this from a propaganda perspective. I'm curious about your thoughts on the different definitions of freedom of speech—especially in censored countries like Russia and China, for example.

Jason:

Yeah. So I'm definitely not a legal expert in freedom of speech, First Amendment stuff here in the US. I'm just spitballing here probably. Yeah, it's definitely a fine line. The thing is a lot of companies are private entities. They have the opportunity to put forth rules for their networks and have content and rules on their site that are conducive to their business. Like if you're a cat lovers blog and you have lots of folks posting about how dogs are better than cats, you have the right to set out ground rules like, I'm allowed to remove those posts because they don't add to the discourse here. But when they become the essential town square or communication platform where they purport to be this kind of space where anyone's message should be allowed it can become problematic. For example, if you were to walk into a town square and say dogs are better than cats no one should be allowed to tackle you and put you in jail. Even if whoever is in that town square really loves cats.

The distinction is between when a platform becomes a town square. A lot of folks have argued that Twitter should have more, more transparent rules around what is allowable free speech on the site. And in some ways the current regime has purported to say we want a more open and more free speech on the site. The problem is just like in a town square, there are certain things you can't say in a town square because that would be so alarming to your fellow citizens that it would cause panic and you probably shouldn't do that and you will be likely tackled. Another example is let’s say you say something so offensive but it's technically legal- you shouldn't walk around assuming that you can get away with it without someone giving you a dirty stare or someone literally walking up to you and challenging you to fight. You may be allowed to say it, but you have to be willing to be able to accept those repercussions.

Carolyn

And add to that that you can be anonymous online where you don’t have to pay the toll for your actions.

Isabelle:

As a data scientist you deal with a lot of data on a daily basis. Do you ever feel like you ever get data overload yourself? And if that does happen, how do you take a break from it?

Jason:

That's a good one. Yeah. As a data scientist, you are hyper aware of how much data is being collected from you because you know behind the scenes activity. There is just so much information being collected and stored and being used to predict future things about you. And so, yeah, I am very much aware that every time I use an app or social media that I'm giving away so much data about myself. And yet even with that awareness, there are times where I'm just like, I just have to opt in. I can't live without Google Maps and I don't know how I would get around and survive and navigate without it. And so there is some element of me that is like, yes, but I still have to live in this world and so I have to participate in some social media. I'd be very curious what the next generation does with their learnings around how we've all been impacted by social media of our generation where clearly we've gained a lot from it, but it's had so many pernicious effects.

Carolyn:

Yeah, Isabelle, how do you feel about social media? Do you ever have that sense of like Big Brother is watching?

Isabelle:

I don't know. Social media has always been sort of a second nature for me because my generation has grown up with it. It's just so accessible and all my friends are on it. If I'm not on it, I seem like the weird one. The weird one left out FOMO. And I definitely feel an overload of it sometimes, and I definitely do feel the need to take a break. But at the same time, it's also I feel like the whole purpose of it is to draw you in and to keep your attention, and I definitely fall for that at times.

Jason:

Yeah. There are folks who hire very well well-compensated, incredibly smart people. And folks who try their best to engage you and keep you on the platform, too. That's why I really like Duolingo. It's a product where you could dive in for as long as you want, but it's also the kind of thing where you can get value out of, you know, just spending a few minutes on it a day. And yeah, I would probably feel much worse about myself if I was working for a company where they were actively trying to addict you.

Carolyn

I've not personally used that app but I have several friends who have. What, what drew you to it? And can you talk about how it works teaching a new language?

Jason

Yeah, it's a fantastic program for getting you exposed to languages that you may have had some exposure to before or the ones that you've just kind of curious about and sort of give you a sense of how people speak. The voices and listening through the app experience is fantastic, especially when a lot of us just don't have the opportunity to hear the language in a not overly robotic way. And so yeah, the app does a great job of both just immersing you right away without forcing you to to read through textbooks or read through grammar logic, although you can dive in if you want to do that sort of thing.

Carolyn:

I feel like things like Duolingo are kind of an antidote to a lot of the saturation we're talking about. Like, you know, opening your eyes to a new culture or a new language, learning something new. It just sort of, you know, builds optimism and away cynicism. Are there any insights or trends as far as what language people are really wanting to learn? Or, any insights into how people are actually using the product right now?

Jason:

One thing we actively are thinking a lot about, which we recognize is really important, is how so many folks around the world are wanting to learn English and what is the most efficient and fastest way we could get them to learn. And oftentimes there are different approaches and many different pedagogical approaches for how to teach someone, you know, different languages. But one of the key things that Duolingo has been spending a lot of time thinking about is how do we teach the English language around the world in order to sort of give folks an opportunity to participate in a lot of conversations that they wouldn't be able to have before. And so that said, we still all want folks to be more diverse, more experienced. But we also recognize that a lot of folks are wanting to learn languages as a way to get access to economic opportunities and to be able to be a part of that is really exciting for me.

Isabelle:

If there is one thing that you could tell our audience about combating saturation in our society, in our day to day lives, what would it be?

Jason:

God. Wow. I don't know. I don't know. I guess there could be a practice or a ritual to think about doing that helps you. It's something that I wish I had more time to do. But one thing my wife and I used to love to do was go for long walks at night. It seems cliche, but that was something that was really cathartic and a nice way to close out a day.

Carolyn:

Well, the last question that we ask everyone that we interview here, because it is a podcast about beautiful thinking, is how would you define beautiful thinking?

Jason:

That's really interesting. When I think of beautiful things, I think of elegant thoughts. And oftentimes when I think of elegant thoughts, it's just things that just feel naturally connected to each other. I don't quite know what I'm trying to describe it from. I guess I'm like I said, I'm not a computer scientist. I didn't grow up studying it. But I feel like I do have kind of a programmer's mindset and sometimes when I'm coding things just start to flow. You get into that flow state and the next piece of code or the next line just flows naturally. And for some reason I want to say that process, that act of going through it and things start logically make sense together, that to me feels like beautiful thinking, but I don't know how to describe it outside of that programming sense. Like what would be the analogy to that elsewhere? But I assume it's just something related to when you're just in a moment and things just seem like they're working and it's you're relying on intuition and it's just flowing out of you. And when you look back and you're like, that was a hopefully a very thoughtful way of expressing that as opposed to just like nonsense that you wrote at midnight.

Carolyn

Perfect. Well, thank you so much, Jason. We really appreciate your time and participation.

Jason:

Fantastic. Thank you so much.