Once in a lifetime, you might get lucky enough to meet someone who’s shaped your core views about design. For me, that was Paula Scher. For decades, she’s designed much of the good work we see in the world — from Citibank’s iconic logo to work for The Public Theater in New York and The High Line. She embodies the spirit that I set out to embrace with my work when I finished art school all those years ago. If you had told me then that I’d be interviewing her in person at my alma mater, IUPUI Herron School of Art and Design, 30 years later, I’d have said you were crazy. Below is an interview I did with her in front of Herron students during Scher’s visit to the school to deliver the Jane Fortune Outstanding Women Visiting Artist Lecture. You’ll see students’ questions folded into this interview.

“If I’m working for a particular corporation, I’ll look at the competitive landscape and work very hard to differentiate them from it. But the trick is that you can’t move them too far because they’ll be scared. It’s like not wanting to go to a party where everybody is wearing black and be the only one in the red dress. What you can do is get them to wear a red belt. That’s moving the needle. It seems like very little but it’s actually quite a lot .”

There’s a term in wine-making: “terroir.” It’s the environment in which a wine is produced — soil, topography, and climate. How has your environment, New York City, impacted your design?

I don’t think it’s a conscious thing. Years ago, a fellow designer Stephen Doyle pointed out that April Greiman and I have work influenced by the coasts we live on. She did big flat areas of color with lots of gradation. The colors tended to be pastel and supercharged. I did a lot of black and red and white, and everything is jammed together with big, long, tall skinny typography. I don’t remember consciously doing that. I became aware of it later when I did so much work in New York. The fact that the projects were New York-based demanded that kind of vocabulary to a degree.

Paula Scher with me in front of visual communication design students at IUPUI Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis.

In the Midwest, the landscape is obviously different with more wide-open spaces. How can these students use the environment to inform the work they do?

You’re probably already doing it. You don’t sit down and say, “I’m going to use my environment to impact the way I design.” You are who you are. You experience what you experience. That is automatically impacting the work. Because a lot of who you are and what you do is unconscious. You don’t plan it. And there’s a lot that is conscious. And when the unconscious and conscious come together in the right way, it’s wonderful.

How do you feel about being described as a female designer?

Why aren’t male designers described as male designers? It puts you in a category before you’ve even opened the door. That’s not so great.

Identity for Philadelphia Art Museum: The logo can be customized with 200 different As (and counting), representing different styles of art and works in the collection.

You divide your time between your place in the city at NoMad, and weekends at your house in Salisbury. Do you use the environments differently to do your work?

I do my graphic design in New York City and my painting in the country. In the country, I’m all alone. I have a little paintbrush and a really big canvas. It keeps me sane because you can’t do both things exclusively. You have to do them in balance with each other.

I understand you listen to old movies when you’re painting in the country?

Yes, I do. I used to listen to jazz, but I got sick of albums. Eventually, I discovered I can paint to a movie if I’ve seen it before. I can’t paint to a movie I’ve never seen — especially if it’s got a lot of action — because I can’t look at it. Westerns can be really hard. But if it’s something like The Searchers or Red River, I know everything that’s going on. It’s fantastic. I can paint to it and still pay attention. Sometimes I put words in the painting that was a part of the dialogue by accident. That’s the only bad thing.

NY office: Pentagram is the world’s largest independently-owned design studio. There are 24 partners world-wide with offices in Austin, Berlin and London and NY.

How has staying at Pentagram for 29 years impacted your evolution as a creative?

I began designing at CBS Records. I worked with a group of really, really smart, talented people, and we competed. There was a golden period of time in my 20s. The experience taught me that you don’t want to be the smartest person in the room because you don’t learn anything. It’s great to be challenged by people that you respect.

When I was invited to join Pentagram, I was completely intimidated. I was the only woman in a group of very famous, very accomplished, talented men. I had to shape up. And that was good. It was good for the work. It was good for me. As the partnership grew, it got better and better. Now I have four women partners in New York. It’s fantastic.

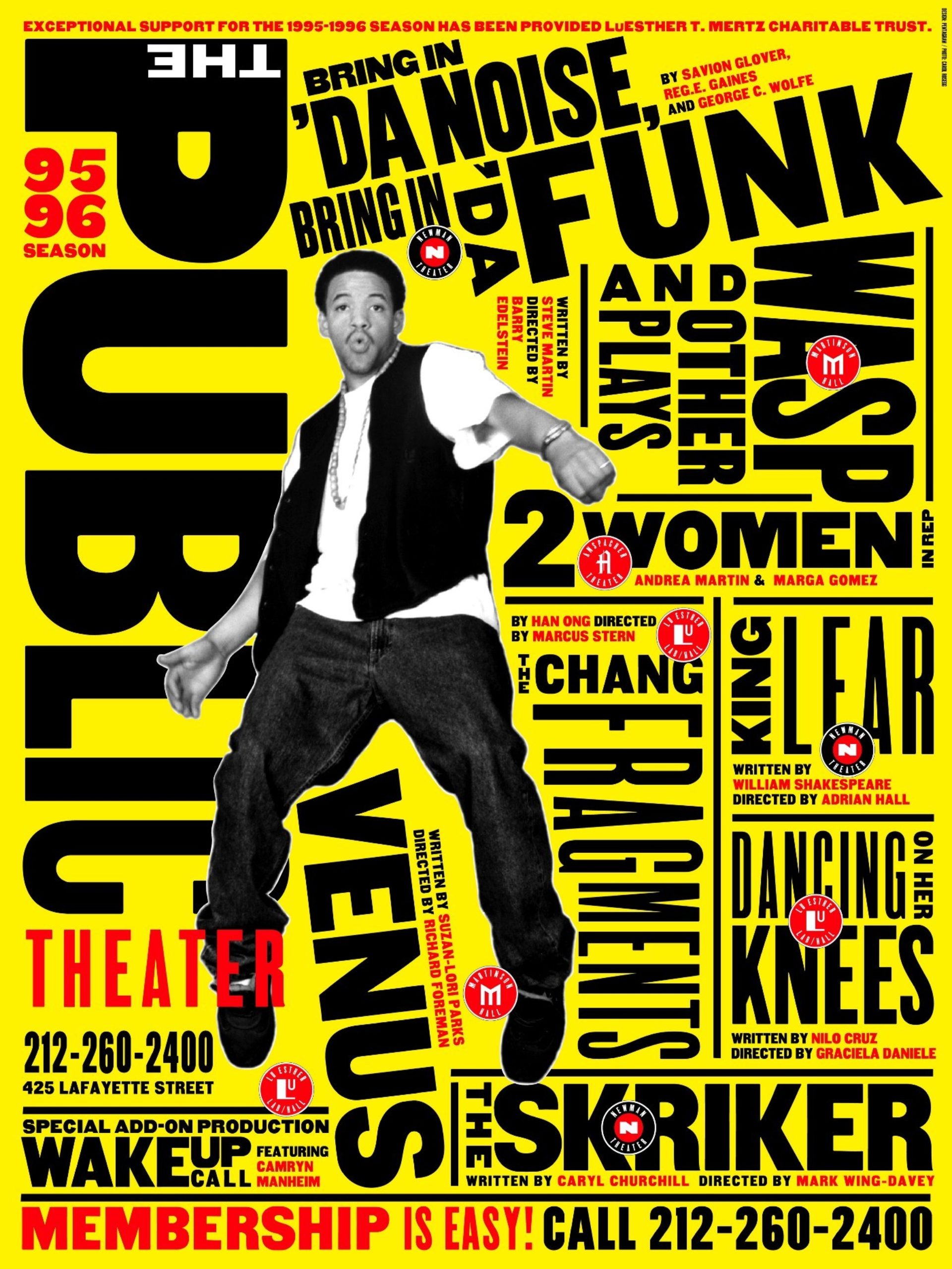

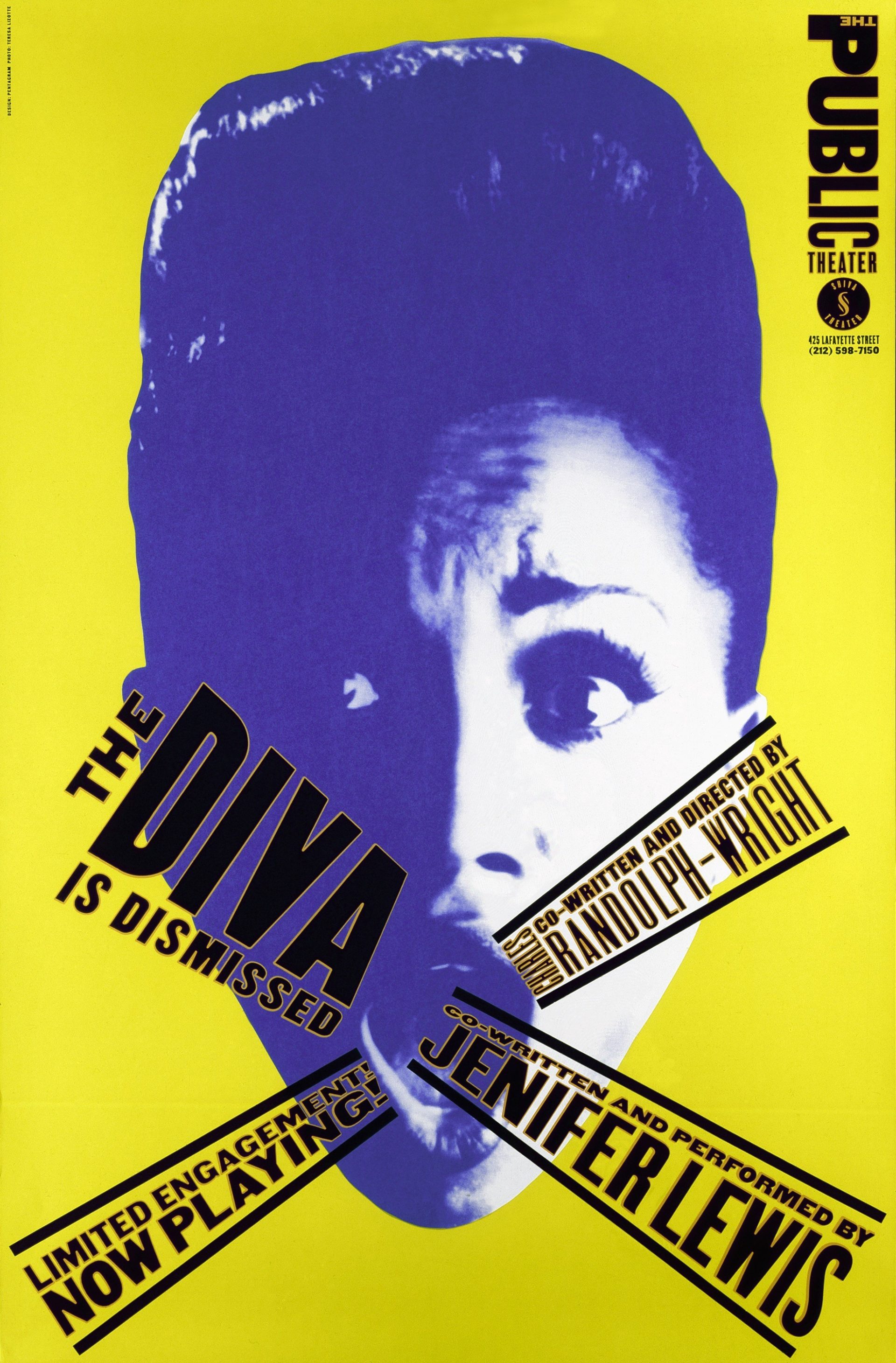

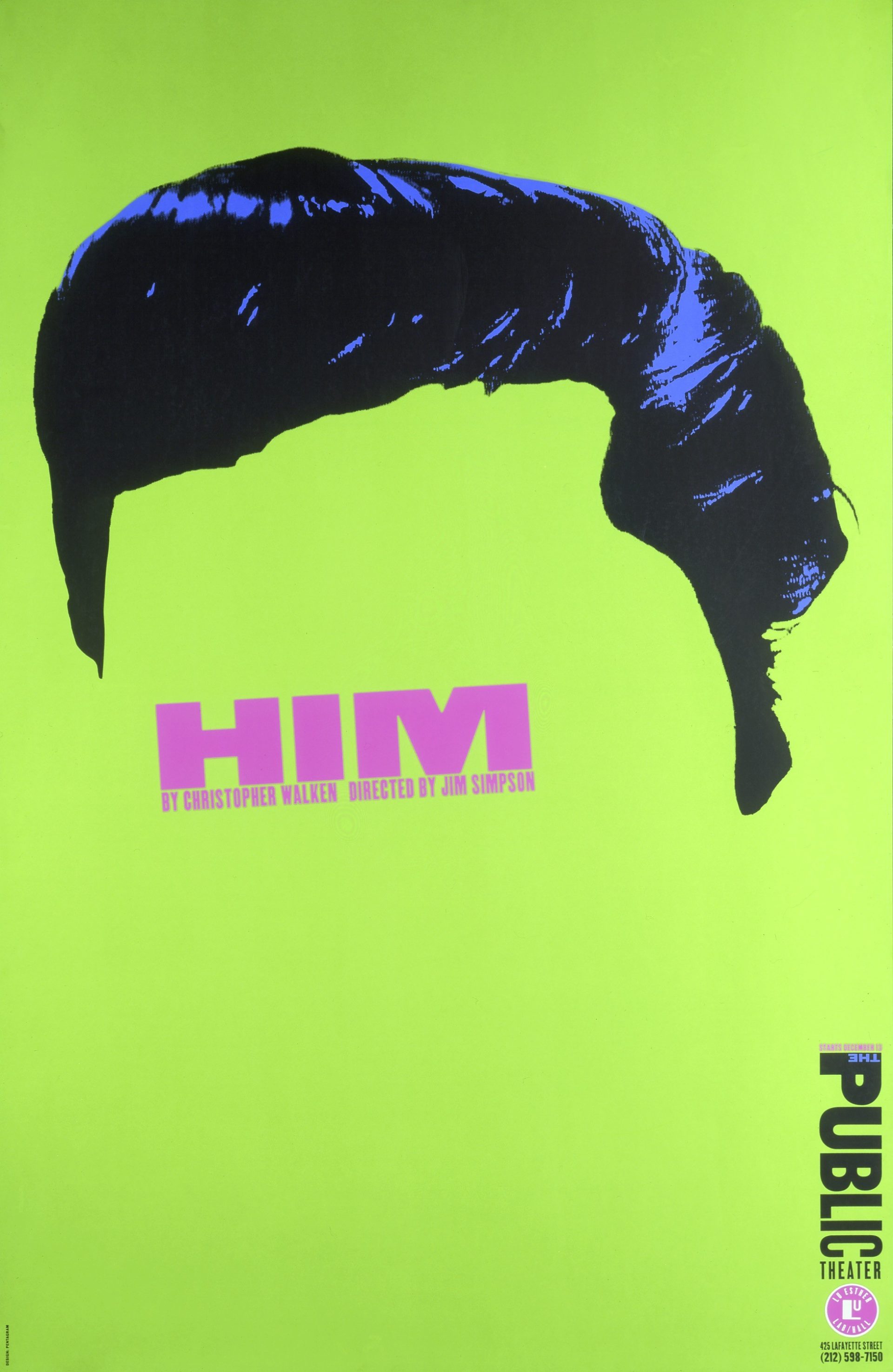

“I still have the client, It’s actually 26 years this year I’ve been their creative director and designer. I’ve redesigned their logo three times. I’ve changed the way they do their posters all the time. I go around and mess around with the theater. It’s a great relationship.”

Talk about the year 1993. It was a pivotal year for you.

Yeah. I got a call from the director of The Public Theater, and I got the best job of my career. I still have it to this day. I’ve been their creative director and designer for 26 years. I’m always changing the way they do their posters. I go around and mess around with the theater. I have a complete art department down there, separate from my art department at Pentagram. It’s a great relationship.

Didn’t you go back and change the logo three times without anybody knowing?

Nobody knows.

“If a recording artist was coming to the company to have their cover done, the product manager would say, “We’re going to get Paula. She’s the best one.” That came from promoting the work.”

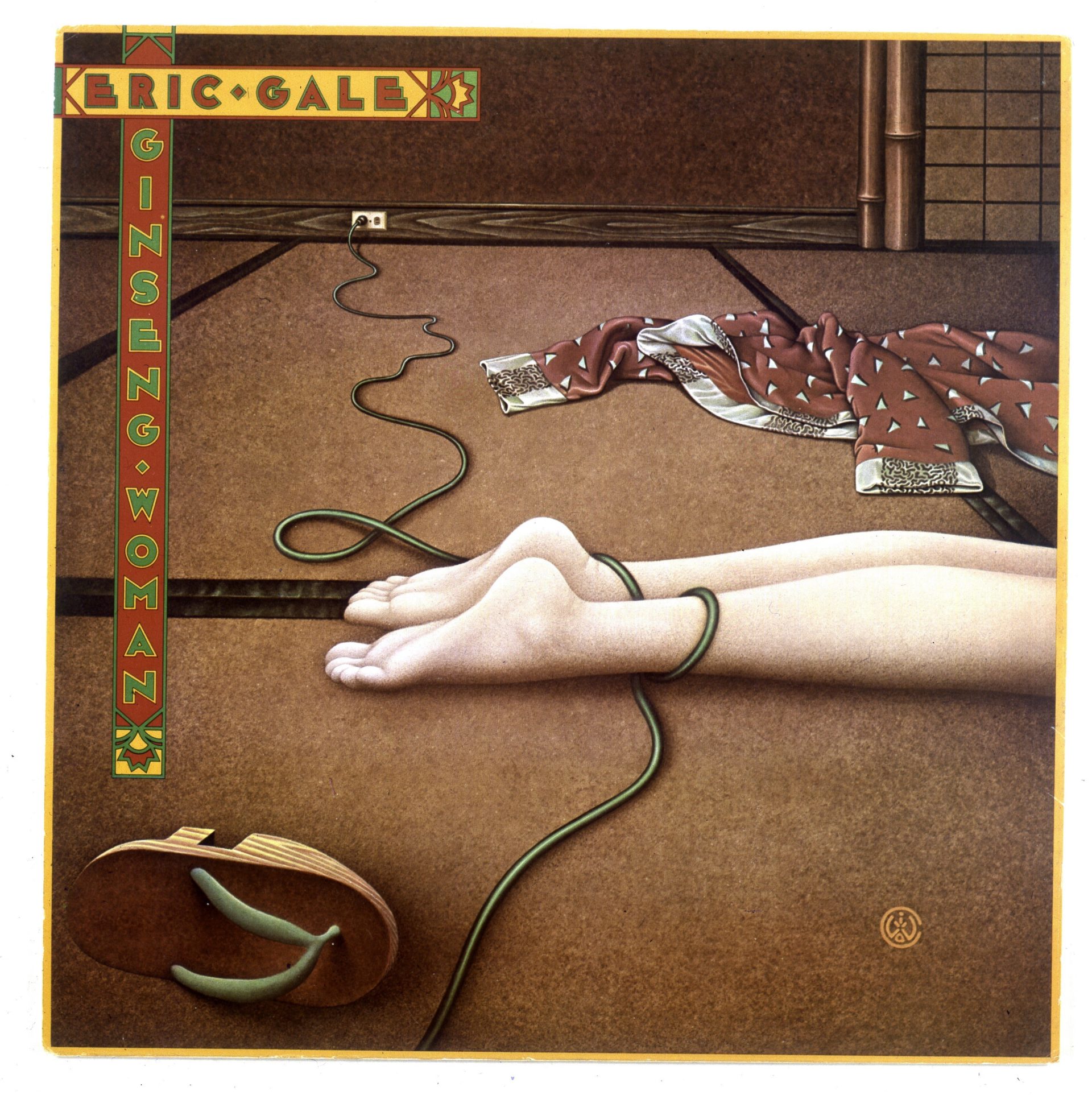

When you used to design album covers, did you like to listen to the music ahead of time?

This was really iffy. If I designed a book jacket, I invariably read the book or read as much of the book as I could. Music was hard because my interpretation of it was not necessarily the band’s. It was better to ask them what they meant or wanted to accomplish with their music.

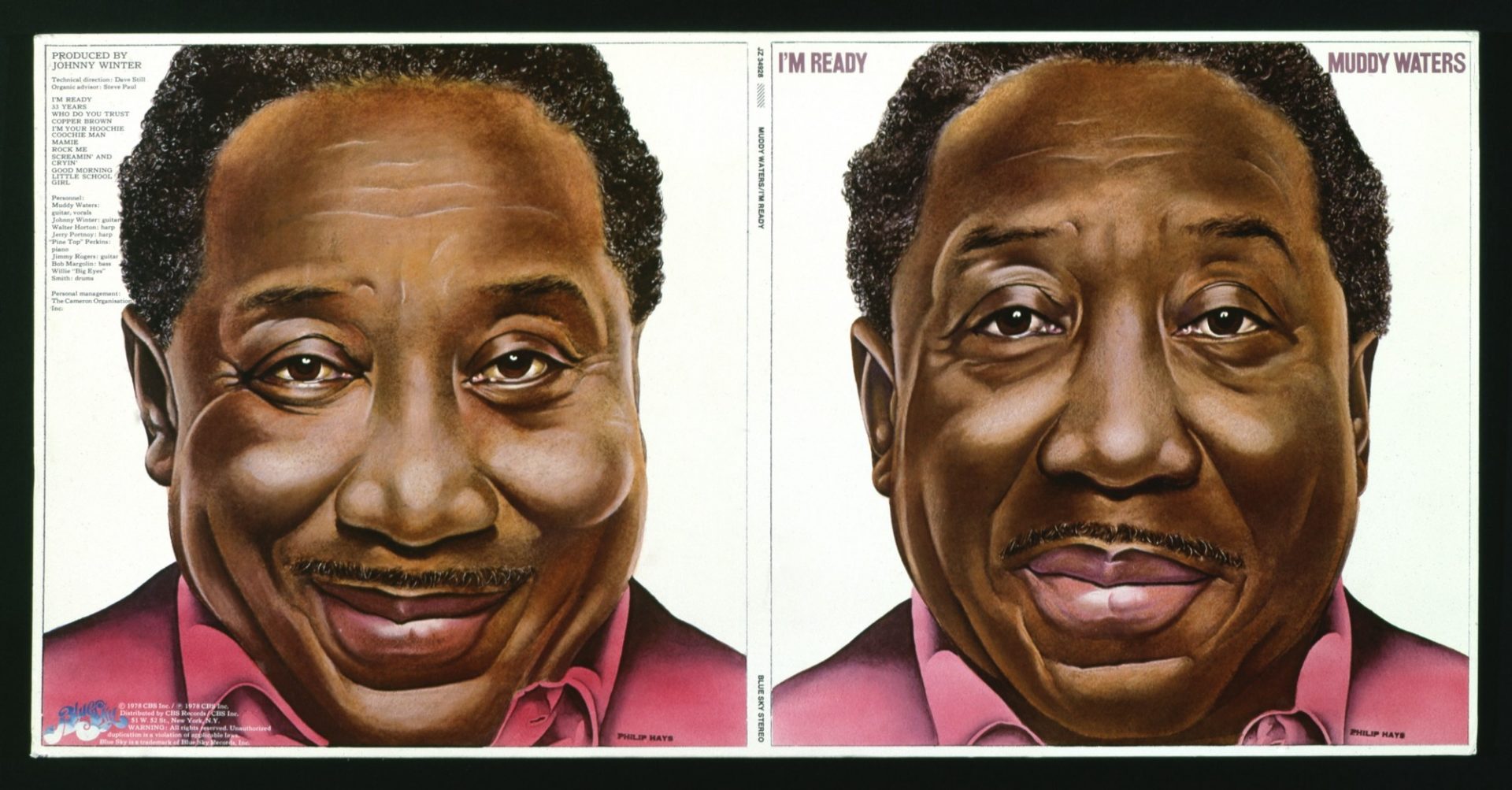

“Muddy Waters had this elastic face that was just so expressive. Phil Hayes, a West Coast artist, painted the best portrait of his cheeks.”

Do you have a favorite musician that you worked for?

Muddy Waters.

Interesting. Why?

For one thing, he was great — very funny and very cool. I liked working with him, and he liked everything I gave him. For one cover, I hired Richard Avedon to shoot him. Muddy came in with his hat on, his coat on. And he was just such a cool dude. Avedon just shoved him up against the door, right against the stark white door, and he took eight big photos with a camera. He pulled them out right away. They were giant pictures. And they were just gorgeous. They were perfect. And he was done.

You mentioned accidentally hitting a zeitgeist when you designed the iconic Boston album cover with a spaceship and the release of Star Wars followed just a year later. Knowing that you didn’t like it then, and you don’t like it now, do you still consider it a success?

I don’t know what to think. You make things, and they go out into the universe, and you don’t really have any control about how people perceive them. I made hundreds of record covers. Some were terrific. Some were terrible. But with Boston,16-year-old boys seemed to like this stupid spaceship. I was 26 when I did it. Every person I know who’s 10 years younger than me thinks it’s the best thing I ever did. I just don’t understand it at all.

I was chopping an onion last year and listening to Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me. The host, Peter Sagal, was telling a story about the earth blowing up and the spaceship and all these cities leaving the earth. And he said, “You know, like the Boston cover.” This was in 2018, and I designed the cover in 1976. There’s something really sick about that. I can’t get a handle on it. I’m trying to like it.

“When I showed them the logo he said, “Well yeah, that’s a good logo for the High Line but our organization is The Friends of the High Line.” And I got very indignant and said, “Well, who cares about the friends of the High Line? Don’t worry about the friends. Nobody cares about the friends. They’ll give money to the High Line, not the friend of the High Line.”

Early on, you had some fairly significant people close to you question your talent. I’m curious to hear how that adversity shaped you.

Which ones? My mother? When I told my her I was going to move to New York to be a designer she said, “Oh, don’t do anything like that. That sounds like it takes talent.”

And your design teacher from your first year. Right?

Oh, Bob Stein. How did you know that? That’s amazing. At Tyler during my freshman year, I had to take his basic design class. He taught the Bauhaus methodology, which I didn’t understand at the time. We worked with rubber cement to glue paper, and if you were sloppy, it made little curly bubbly things that looked awful. I wasn’t good at it. I took this course, and he said, “Why are you in art school?” I said, “I want to be an artist.” And he said, “Cooking is an art.” True quote.

A few years later, when I was working at CBS Records, I got a call from Bob Stein. He was teaching at the Institute for the Arts. He invited me to his class. I never could stand this guy, but I went out of curiosity. And I thought, “How is he going to introduce me?” He stood up in front of the room and he said, “This was a former student of mine, and I can take absolutely no credit at all for her success.”

I think everybody in this room at some point has experienced that. Karyssa, a student, would like to know: “What was your most memorable time as a student?”

I had a fantastic teacher and mentor named Stanis Zagorski, a Polish illustrator with a thick accent. If he said something was good, your whole year was made. Mostly he said, “Probably you should do over for me better.” You would argue with him, and he would say, “Do over for me better,” and that was it.

He gave me a piece of advice that really shaped me. We were working with a press type. There were very few font choices, so a lot of time you worked with Helvetica. Some people in my class were very neat, and they would line everything up beautifully. I would make some whacked-out piece of artwork and then put Helvetica on. It would bubble and crackle and look like holy hell. Mr. Zagorski knew I could not operate this press type, so he said to me, “Why don’t you illustrate with type?” That was the beginning of me beginning to see that type had spirit.

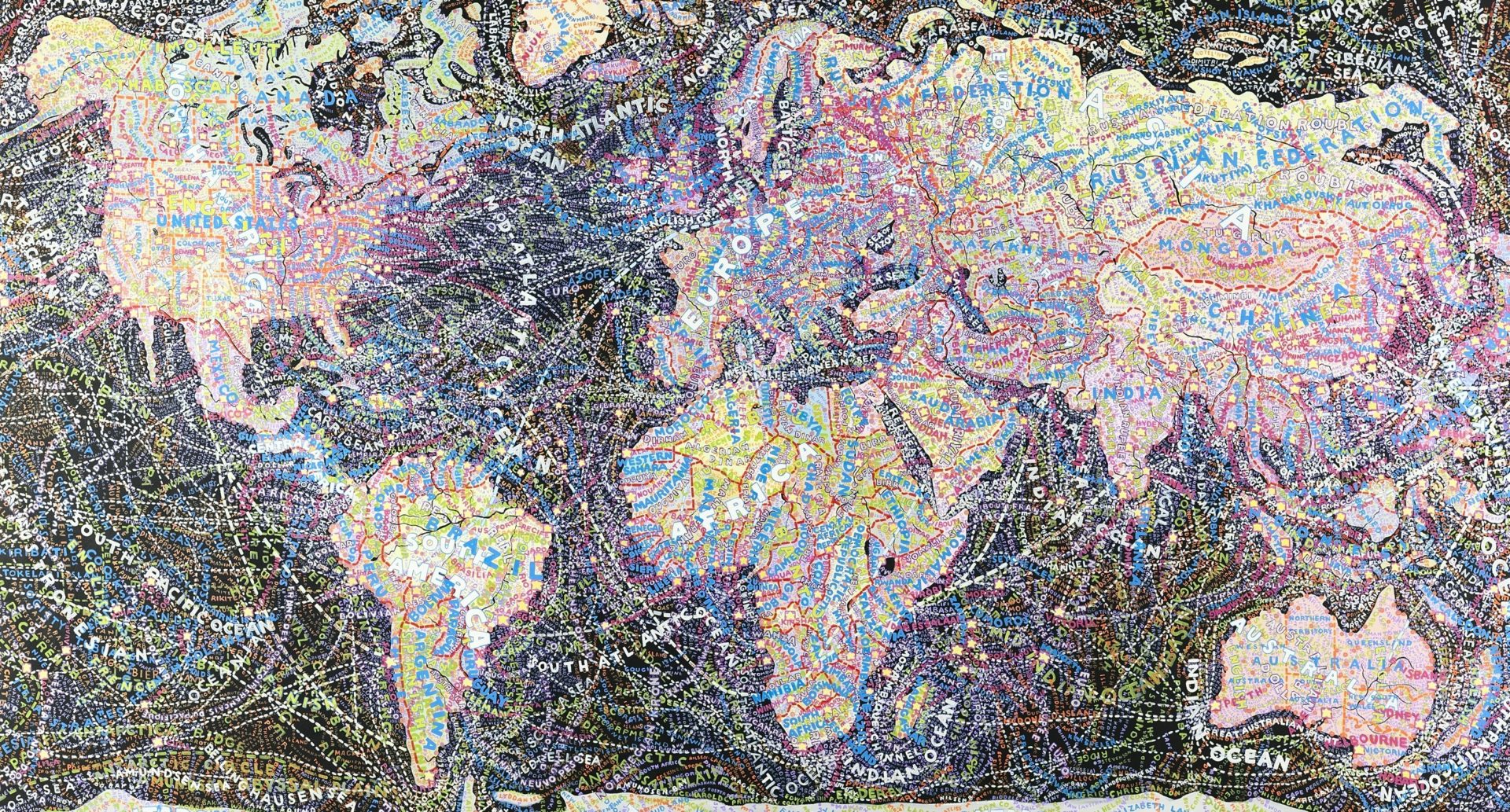

“World Trade”: An exhibition at The Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, 2012, in collaboration with Paula Scher. “Paula interprets society’s approach to data and our visual representation of the trafficked environment. Through her large-scale cartographic paintings, she has created a novel way of mapping traditional information, while subjectively twisting and confounding it.”-Bryce Wolkowitz

Jennifer, another student, would like to know: “What is your favorite letter in the alphabet?”

P.

Conventional wisdom says we get better with experience. But you once told a client: “Some days, I’m not as talented as other days.” Can you tell us that story?

I used to work for Simon & Schuster. They had an art director who had been there a million years. He was a really cranky, crabby man named Frank Metz. I would send a jacket design to him, and he’d say, “Paula, when I send you a project, I really expect that you’re going to give me your best. And I have to say this recent piece of work is not up to your usual standards, and I, for one, am disappointed.” What are you going to do? I thought it was a perfectly decent thing that I sent him. And that’s when I said, “Some days you’re more talented than other days, I guess.”

Do you still have those days?

I still do things that are pretty awful. It’s part of the process. You have periods of tremendous productivity and other periods where you’re fallow. The fallow periods are really important because that’s where you’re refiguring it out. You have to work through it in order to discover something new. When you’ve had a successful run, that’s very dangerous because you’ll only repeat and never be quite as insightful as you were the first three times you did it.

When you have a client involved, you have to be careful professionally that you’re not refiguring it out on somebody else’s dollar. It seems scary but it’s really part of personal growth. The parts of yourself you think are failing are actually the things helping you grow.

“The identity of Parsons The New School was incredibly controversial when I did it. I got blasted all over the internet and everybody hated it. And then, it stopped. And do you know why it stopped? The senior year graduated and the next year came in and they didn’t hate it because they moved into it.”

Savannah, another student, would like to know: “What question have you never been asked that would say a lot about you?”

How do I deal with being short?

Do you think it’s possible to be a purist as a designer?

Michael Beirut does. He got it from Massimo Vignelli. Massimo thought people were terrific or terrible. And he hated my typography. Years ago, he hated the things I did that were considered post-modernism. Right before he died, we were friends. I ran into him on the street, and he was with some clients, and he said, “Do you know Paula Scher? Terrific designer. Terrific. Used to be terrible.” He would argue that you could be a purist, but I don’t think so, no.

Kaitlin, another student, would like to know: “How do you create during a time of grief?”

It depends how upset I am. Sometimes if something is going terribly or you’re mourning something, you can retreat into your work, and it can be incredibly helpful. Sometimes, you’re too upset to work. It’s different for everybody. But I don’t think that grief means that you can’t produce. A lot of people produce out of sadness.

You’ve talked about how you do some of your best work in mundane moments. Is that something that you build into your process, or do you just take advantage of those moments when they happen?

I realized this when I analyzed how I got ideas. Sometimes I feel more productive and can do things quickly while at other times, I’m really struggling. The worst thing for me is thinking about too much. I’m intuitive, and my first idea is likely to be my best because I usually come to it when I’m thinking about something else.

I take a lot of taxi cabs in New York City, and I’m generally bored in them. I’ll be looking out the window and thinking about something else, and suddenly I’ll get an idea. By the time I get to the office, I know what to do. On the other hand, if somebody puts a brief in front of me and says, “Solve this,” there’s no way I could. You have to get space and allow your subconscious to work or you’ll never make it.

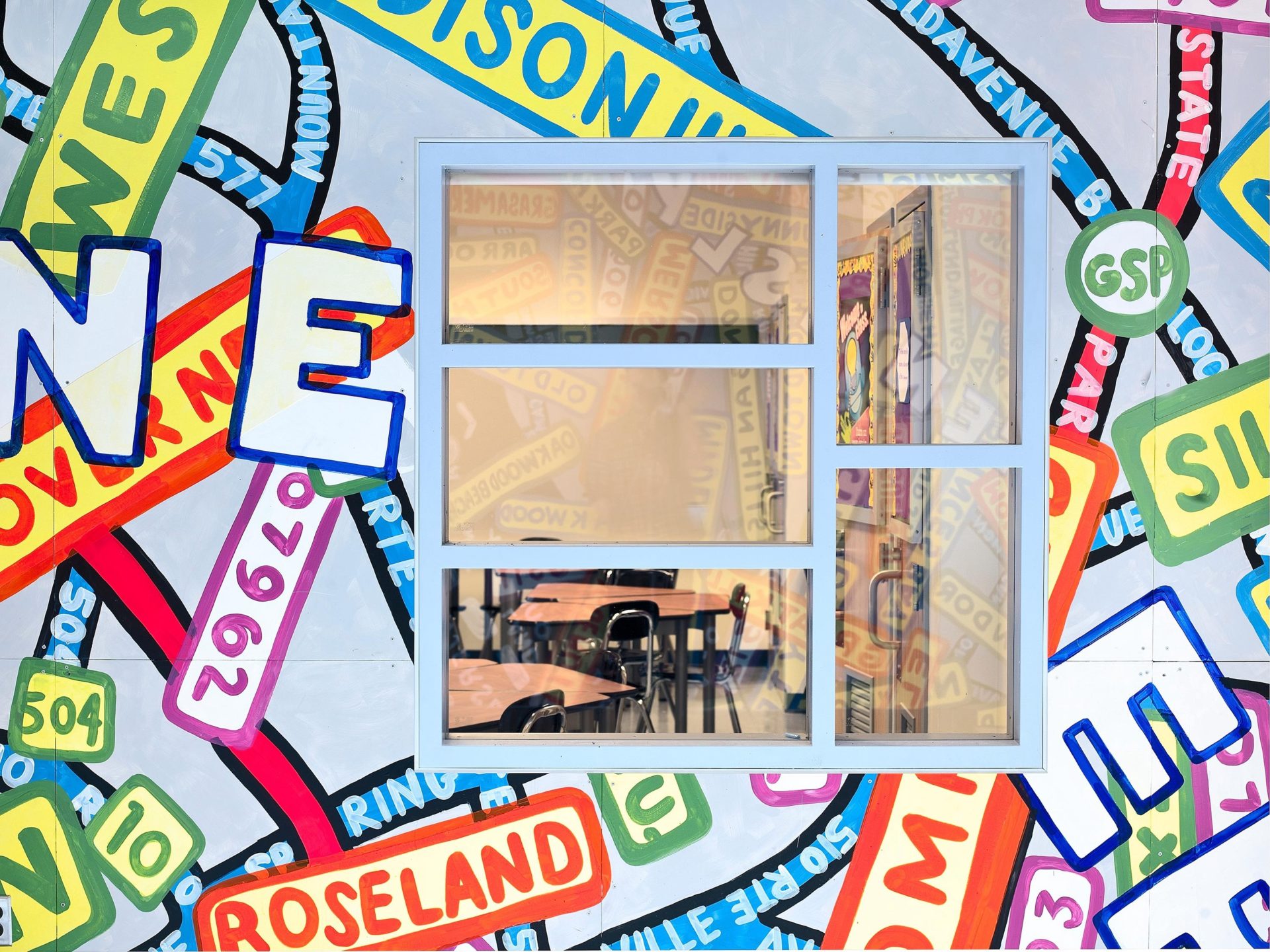

Queens Metropolitan Campus: “Scher has merged her environmental graphics and painting to create a remarkable new work: a pair of murals at the new Queens Metropolitan Campus in Forest Hills, which includes Queens Metropolitan High School and the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School, a middle school.”

Eli, another student, says, “People often say there’s no way you can come up with a great solution on the first try. Why is that?”

Everybody is different. I’ve heard educators say things like, “Well, it’s too easy. Go back and rethink it.” But what’s wrong with too easy? Sometimes too easy is so natural and so pure. It’s really a value judgment you have to make. I have a problem where my first idea is terrific but then we have a lot of trouble coming up with others because you usually show three or four approaches. We’re always struggling to make them equivalently good because I don’t want to show anything that I wouldn’t be just as happy if they took. I find it very hard to build out equivalent presentations.

You’ve been teacher at SVA for years. You’ve said that every student needs to develop the ability to explain, defend and promote their own work. Can you explain what you mean by promotion?

I don’t mean Instagram. When I was at CBS records, I was in charge of producing 150 album covers every year. The recording artists had contractual cover approval, so I worked very hard to develop a reputation — which is still a reputation I think I have today — of being a very good designer who was not afraid to defend her work. It was actually a good position for a woman because it took the sex out of the work. At that point in the ’70s, there were very few women working in the field.

If a recording artist was coming to the company to have their cover done, the product manager would say, “We’re going to get Paula. She’s the best one.” That came from me promoting the work. Most people don’t know what they’re looking at, and they want to be led. You have to teach them how to see, but they have to believe you.

“You want to be able to work for corporations. It’s important that designers, good designers, do that because that’s the stuff that proliferates our life.”

"You don’t believe in drawing a line in the sand for the kinds of clients that you take on. What criteria you have for a corporate client versus somebody in the public sector?

Most large corporations fall into a gray area. Most of what they do is needed. Some of what they do might be questionable. But if you demonize everybody, you leave yourself with nothing to eat. It’s important that good designers work for corporations because that’s the stuff we look at. If it’s lousy, we’re all left looking at it because it’s going to be everywhere. The goal is to raise the expectation of what something can be, how something can be designed. Change that expectation.

How do you know the moment you’ve sold something, and you just need to back away and get out?

Say you have a presentation where you’re trying to develop enthusiasm. You walk into a room where everybody is gathered and begin presenting. Their level of excitement is going to go up in relationship to how you’re presenting it. They’re going to become very enthusiastic, and you’re going to hit some incredibly high point. At that moment, one person — it’s usually somebody who missed the first meeting, was late, or didn’t want to hire you in the first place — starts to rebut. They take the feeling way, way down just to about where you were when you came through the door.

So you answer that rebuttal and you build it back up, maybe a little bit more than halfway. You’ve persuaded them around the room, and they’re nodding. End the meeting there. That’s where the meeting has to stop because the rebuttals will continue. The mood will go down even lower, and you’ll lose the whole thing. Get out the door. Later they make think about it and give you the same bad result you didn’t want, but at least if you stopped, it didn’t go all the way to disaster.

How do you combat the current data glut?

That’s a real problem, but it exposes itself. I saw a woman give an AI presentation from Columbia. She used the example of designing a Starbucks breakfast campaign. She said her data might show most people like the color yellow so you could turn the Starbucks logo yellow and solve the problem. And I said, “Why in the hell would anybody want to do that? It’s so terrible and hackneyed and such a bad idea.” And yet, I bet if you took the data, that would be proven to be a good idea. That’s not what you’re designing for. You’re not designing for this year. You’re designing for next year. The data is no good because the data is only telling you what’s going on now. You can’t be a good designer operating that way. You’ll be held back.

What would you tell a young designer looking for their first job?

That it doesn’t matter if you bounce around in your 20s. In your 20s, you have lots of growth because you don’t really know all that much. You learned a certain amount in school. You’ll find the real-world functions very differently from school. You’re not judged by the same standards, and clients don’t behave anything like teachers. You suddenly have to readjust how you think and how you operate.

What’s most important for a young designer is not to take a job for the money. Take a job for what the place produces because that’s what you’re going to be making. If you think you’re going to come in and make something so much better than they’re making, that’s not going to happen. If you don’t think the work is good, don’t work there.